Winging It At the Met

Winging It At the Met

Nicolaus Mills: On the Met’s New American Wing

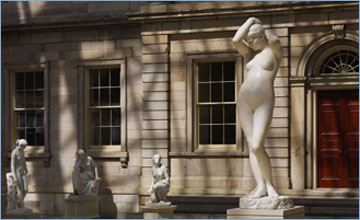

When New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its new American Wing in May 1980, its most impressive asset was the spacious Charles Englehard Court, which featured the Greek Revival limestone façade of Martin E. Thompson’s 1822 Branch Bank of the United States. The glass-enclosed and roofed court, always filled with light, was a welcoming place where large-scale sculpture, mosaics, and architectural elements were never forced to compete with each other for attention.

The sculpture in the center of the court were limited in number and surrounded by plantings. At the southern end of the room, far from the Branch Bank façade, the pillared loggia designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany for his home at Oyster Bay, Long Island had a wall to itself. Even the massive marble, oak, and mosaic fireplace, taken from the Fifth Avenue home of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, didn’t overwhelm the space it took up on the eastern side of the court.

When the newly reconfigured Englehard Court and American period rooms re-opened this May as part of a $100-million project to renovate the entire American Wing by 2011, this sense of spaciousness was gone. Breathing room is now at a premium in the Englehard Court. The plantings have been removed, and with 30 percent more space for displaying work, the Met hasn’t wasted an inch. It has placed sixty pieces of sculpture, mosaics, and stained-glass windows on the court’s ground floor.

Some of the additions fit perfectly. Very close to Thompson’s Branch Bank of the United States are two monumental French-style lamps, designed by Richard Hunt Morris for the Met’s entrance in 1902. Beautifully restored, the lamps complement the bank entrance, as they would the entrance of any building. But not too far away stands a massive limestone pulpit and choir rail from All Angels Church that was carved by Karl Bitters, best known to New Yorkers for the fountain in front of the Plaza Hotel. In a room filled with religious objects, the pulpit would be perfect. But in the Englehard, Court the pulpit simply dwarfs everything around it and feels context-less—the Met’s equivalent of a stairway to heaven.

Still more troubling are the cases of ceramics and pottery that now dominate the new mezzanine balcony. At a distance the cases make the museumgoer feel as if he were entering an expensive department store. Up close, the department-store feel quickly disappears, but the cases are so crammed with objects that it is hard to focus on any single piece.

Behind these changes lies the growth of the Met’s American collection. In the last twenty-nine years, the Met has acquired 3,400 works, and rather than keep them in storage or hidden-away display cases, the museum has decided to make them as accessible as possible. It’s hard to disagree with the Met’s logic, based as it is on the generous premise: better to have museumgoers see more of what the Met owns, even if that creates new problems.

Behind these changes lies the growth of the Met’s American collection. In the last twenty-nine years, the Met has acquired 3,400 works, and rather than keep them in storage or hidden-away display cases, the museum has decided to make them as accessible as possible. It’s hard to disagree with the Met’s logic, based as it is on the generous premise: better to have museumgoers see more of what the Met owns, even if that creates new problems.

And to be fair, the Met’s desire to get more on display can often make viewing better. The removal of the plantings that once dominated the center of the court has meant that it’s possible to get closer to the sculpture there. In the case of the most dazzling piece of sculpture in the court, August Saint-Gaudens’s “Diana,” a smaller gilt bronze version of the “Diana” weathervane he did for the tower of the old Madison Square Garden that Stanford White completed in 1891, that closeness is a particular virtue. It lets one absorb the detail—not merely the lithe silhouette—of one of the few nudes Saint-Gaudens ever did.

An even greater gain has come from the changes made to the period rooms of the American Wing. There are now twenty of them, and it is possible to move through them in chronological order, going from a 1680 room from the Hart House in Ipswich, Massachusetts to the living room that Frank Lloyd Wright designed between 1912 and 1914 for the Frances Little summer home in Wayzata, Minnesota. The period rooms, which have been repainted, now have fiber-optic lighting that makes it possible to see the furniture in them more precisely. In addition the rooms come with touch screens that are easy to operate but not so overloaded with information that they constitute a distraction.

If all goes as planned, the work on the American Wing will be finished by 2011, and the Met’s vast collection of American painting, particularly its Hudson River landscapes, will be back in their familiar places. That day cannot come too soon. In the American landscape tradition, the wilderness is vast, man is small—his limitations as plain as the sky and woods that dwarf him. But that cannot be said for the sculpture and other objects that dominate the Englehard Court and the American period rooms. They can take your breath away with their beauty, but humility is not essential to them. Most of the time, they never let you forget how much they cost and who paid for them.

Nicolaus Mills is a professor of American Studies at Sarah Lawrence College and co-editor with Michael Walzer of the forthcoming Dissent-Penn Press book, Getting Out: Historical Perspectives on Leaving Iraq. Photos courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art.