We Have a Pope: An Absurd Vatican

We Have a Pope: An Absurd Vatican

L. Quart: An Absurd Vatican

Nanni Moretti is one of Italy’s most original and beloved filmmakers. He not only directs his films but collaborates on them as scriptwriter, producer, and actor. He is a man of the left but also an ironist who views modern society with a wary, often humorous eye. Moretti’s best known films in the United States are the satiric, light-hearted, yet moving Caro Diario and his more melancholy The Son’s Room.

Nanni Moretti is one of Italy’s most original and beloved filmmakers. He not only directs his films but collaborates on them as scriptwriter, producer, and actor. He is a man of the left but also an ironist who views modern society with a wary, often humorous eye. Moretti’s best known films in the United States are the satiric, light-hearted, yet moving Caro Diario and his more melancholy The Son’s Room.

Moretti’s new film, We Have a Pope, combines both the sweet comic elements of the former with the darker vision of the latter. Moretti is not a believer, but the film avoids engaging in a frontal attack on the crisis-ridden Catholic Church’s hypocrisy, corruption, and political gamesmanship. In fact, Moretti said in an interview, “I preferred not to allow myself to be conditioned by current affairs. It is a made-up story: my film is about my Vatican, my conclave, my cardinals.”

The film cross-cuts two narratives. The first and more poignant one centers on the newly designated Pope, a dark-horse candidate, Melville (played by the venerable veteran actor, eighty-five-year-old Michel Piccoli). Melville, after his election, refuses to come to the Vatican’s balcony to address the faithful throng and, in anguish and confusion, wanders incognito through the streets of Rome. The other narrative follows the College of Cardinals at the Vatican anxiously waiting for Melville to assume the Papacy. We see the Vatican spokesman tell the Catholic faithful that Melville has retired to his chambers to pray before taking on the post, an act that supposedly displays his admirable humility.

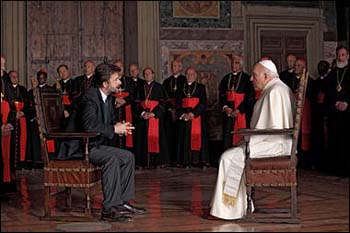

The latter narrative is less successful than the former. The cardinals are portrayed as foolish, comic, even childish figures. There is no cardinal that resembles, say, Timothy Dolan of New York, whose amiable surface covers a politically aggressive, power-loving, and doctrinally rigid core. In fact, at the beginning of the conclave, all the cardinals are thinking, “Don’t pick me.” Moretti sees them as fallible men who while away the time playing solitaire and doing jigsaw puzzles—and eventually a tiresome, full-scale volleyball tournament, initiated by a non-believing psychoanalyst, Bruzzi (Moretti himself), brought in to cure the depressed Melville. Bruzzi is stymied in his work by the Church’s prohibition about talking to Melville about his mother, sex, depression, or unfulfilled fantasies.

Bruzzi’s need to control and overweening self-confidence—“I’m the best psychologist”—can be funny, as when he holds forth to the cardinals about how biblical lines like “my heart is blighted, and withered like grass” prove that depression has not been invented by analysts. However, Moretti talent as an actor lies solely in projecting intellectual arrogance and aggression, and his shtick wears thin after awhile. This problem isn’t unique to Moretti’s role in the film. The Vatican spokesman’ enlists a member of the Swiss Guard to cast his shadow and occasionally rattle the curtains of the papal bedroom to indicate a human presence so nobody will think he’s disappeared. It’s funny one time, but Moretti repeats the comic conceit too often.

But Moretti’s view of the cardinals slyly succeeds in undermining the augustness and power of the church. They end up being ordinary, cappuccino- and doughnut-loving men who wear robes that bestow upon them underserved status and reverence from the faithful.

Still it’s Melville who is at the heart of We Have a Pope. Shuffling and stumbling along the streets of Rome, he exudes a painful pathos, but also dignity. He has lost his direction in life: one suspects that he not only lacks confidence but has begun to question his faith. Sent to the city’s “second-best” psychoanalyst—Bruzzi’s estranged wife (Margherita Buy)—he pretends that he’s an actor. (Moretti sends up not only religion but analysis, by giving her a pet theory, “parental deficit,” to explain neuroses.) It’s not quite a lie, since as a young man he wanted to be an actor, but failed the audition for an acting academy.

The workings of fate take him to a hotel where he runs into an acting troupe. As he watches them rehearse Chekhov’s mournful The Seagull, he momentarily recaptures his youthful passion, recalling lines from the play and identifying with its vision of shattered hope. The scene subtly suggests that he has now been thrust into another role, one that demands a performer’s skill on a much bigger platform. It’s the film’s most resonant metaphor—that the whole world, and especially the Church with its elaborate pomp and rituals, is a stage. The idea of assuming this hieratic role has made Melville profoundly unhappy, but the three days he spends in hiding give him a new lease on life.

When Melville finally returns to the Vatican, he makes an unexpected speech stating that he can’t lead the Church, which brings the cardinals to tears. As a perceptive writer friend of mine said after seeing the film, “The despair of the Cardinals after his abdication went beyond the shock of the worldly debacle,” implying “that no one is running the show, either in the church or in the cosmos—we’re now on our own.”

Moretti’s film contains too many wearisome comic routines, and Melville’s despair and alienation from his new exalted role could have been probed more deeply. However, though the film may seem too light and uninterested in a frontal attack on the Church’s transgressions and dogmatism, it has constructed a cunning portrait of an institution that is patently absurd and all glittering surfaces.

Leonard Quart is the coauthor of American Film and Society Since 1945 and a contributing editor at Cineaste.