The Organized Poor and Behind the Beautiful Forevers

The Organized Poor and Behind the Beautiful Forevers

Sengupta: Be-hind the Beau-tiful Forevers

Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity

by Katherine Boo

Random House, 2012, 288 pp.

In her remarkable book about slumdwellers in Mumbai, India, Katherine Boo brings to light a country of “profound and juxtaposed inequality,” where more than a decade of steady economic growth has delivered shamefully little to the poorest and most vulnerable. But though at first a heartfelt indictment of the processes of economic liberalization and privatization underway in India, the book slides into a troubling narrative about the roots of the country’s poverty and squandered economic potential. As a result, Boo loses the possibility of making a truly empowering statement on India’s current predicament.

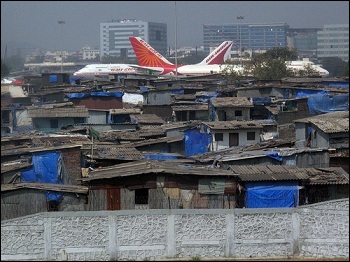

Behind the Beautiful Forevers is a beautifully written book. Through tight but supple prose, Boo presents an unsettling account of life in Annawadi, a “single, unexceptional slum” near Mumbai’s international airport. The slum lies beside a “buzzing sewage lake” so polluted that pigs and dogs resting in its shallows have “bellies stained in blue.” We meet “spiny” ragpickers rummaging through rat-filled garbage sheds, destitute migrants forced to eat rats, a girl covered by worm-filled boils (from rat bites), and a “vibrant teenager” who kills herself (by drinking rat poison) when she can no longer bear what life has to offer. Visitors to the airport, however, are spared the sight of this slum and its struggling inhabitants, who live with the constant fear of demolition. Annawadi is hidden from view by a wall that carries an advertisement for stylish floor tiles—tiles that, unlike the slum, promise to stay “beautiful forever” (hence, the book’s title).

As Boo explains in an author’s note, everything in the book is real, down to all the names. Though this work of nonfiction reads like a novel, it is the product of years of methodical observation and research. Boo chronicled the lives of Annawadians with photographs, video recordings, audiotapes, written notes, and interviews, with several children from Annawadi pitching in upon “mastering [Boo’s] Flip Video Camera.”

The intimate view of life provided by Boo is embedded within a larger concern about the government’s role in “the distribution of opportunity in a fast-changing country.” In these uncertain times—an “ad hoc, temp-job, fiercely competitive age”—has the government made things better or worse? In a bid to answer this question, Boo consulted more than 3,000 public records, obtained through India’s Right to Information Act, from government agencies such as the Mumbai police, the state public health department, public hospitals, the state and central education bureaucracies, electoral offices, city ward offices, morgues, and the courts.

The verdict, chilling in its details, is that there is a deep rot at the heart of the Indian state. The utter callousness of government officials is matched only by the utter vulnerability of the poor, who must daily navigate “the great web of corruption.” Police officers batter a child, aiming for his hands, the body part on which his tenuous livelihood depends. Doctors, at a government hospital, alter a burned woman’s records to absolve themselves of blame for her gruesome death. A school, meant for the poor, is closed as “soon as the leader of the nonprofit has taken enough photos of children studying to secure the government funds” (in contrast, a school funded by a Catholic charity “takes it obligation to poor students more seriously”).

In Boo’s rendering, the state not only fails to provide the basics of a decent life to vast numbers of citizens, but is wholly predatory. As people learn to survive the blows of this rapacious state, their expectations as well as their “innate capacities for moral action” are altered. Boo tells us that in Mumbai, a “hive of hope and ambition,” there is no dearth of young people who believe in “New Indian miracles”—that they can go from “zero to hero fast.” In Annawadi, however, a series of encounters with greedy, ruthless government officials ensures that such dreams are crushed, even the modest one of “becoming something different.” A boy, wrongfully accused of murder, reconciles himself to the belief that the Indian criminal justice is a “market like garbage,” where “innocence and guilt [can] be bought and sold like a kilo of polyurethane bags.” His mother, exhausted by her tussle with a “justice system so malign,” is one of the many adults who keep walking “as a bleeding waste-picker slowly dies on the roadside.”

If Boo’s aim is to shatter the smugness of those who still believe that India is “shining” or that “trickle down” is working, she does very well. But in a country where corruption, poverty, and inequality are the subjects of heated and continuous debate, what are the politics of this powerfully written and cleverly marketed book? (The book has elicited nearly universally favorable reviews, in high-profile venues such as the New York Times and the Colbert Report). Where does it fit in the larger conversation?

The truth is that it is no longer terribly novel to challenge the idea of a “shining” India. After more than three years of sagging growth, massive corruption, shrinking investment, and shockingly poor records on health and education, only a handful of ideologues will insist that India is still doing brilliantly. (Boo’s narrative spans from 2008 to 2011.) For the garden-variety neoliberal, the argument has shifted noticeably, from celebrating India’s “shining” to cataloguing the causes of its all-too-palpable dulling. The lead story in a recent issue of the Economist, “How India Is Losing Its Magic,” is but one indicator of this shift.

The major disagreements today are not over whether something has gone wrong, but about why it has gone wrong. The pro-market orthodoxy has a ready diagnosis: “governance failures” are destroying the effects of sound economic policy and youthful, entrepreneurial drive. (The Economist makes this point with characteristic self-assurance. India is “losing its magic” because of “the country’s desperate politics,” and “the state, still huge and crazy after all these years.”) Examples abound of floundering government-funded social programs and botched anti-poverty schemes. Even corruption, now undeniable in its mammoth size and disastrous effects, is seen as a vestige of the old state, a stubborn ancien régime that has refused to keep pace with the liberalizing economy. The attendant prescriptions are easily deduced: scale back the state as much as possible, dismantle its unworkable social programs, and slap on an ombudsman to keep wayward civil servants in line.

Boo offers no such “solutions.” A Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist knows better than to swat the reader with overt messages. Yet with its exclusive preoccupation with government failure–Boo does not sift through the public records of international organizations or large corporations, after all–the book’s subtle alignment with the neoliberal narrative is unmistakable. For a much-celebrated work that, on the whole, offers an extraordinarily sensitive portrayal of the aspirations, disappointments, and “deep, idiosyncratic intelligences of the poor,” this is most worrying. While Boo provides an accurate account of the state’s repressive and arbitrary proclivities, she gives less than due consideration to the sort of state the poor might actually want. Some of the most urgent struggles today are to increase public funding for health and education, to universalize the reach of social security measures, and to expand the ambit of the legal system in order to secure recognition and entitlements from the state. Led by slumdwellers’ groups and other severely under-resourced organizations, these struggles have rarely met with success. News of municipal bulldozers erasing shantytowns is certainly far more common than that of social movements extracting concessions from the state. Yet in the new India of gleaming skyscrapers and luxury shopping malls, the presence of those who resist—who valiantly fight back—is as undeniable as that of those who are crushed by the weight of change.

It is not surprising that the voice of the organized poor has eluded Boo. She is preoccupied with documenting “poor on poor crime”—and more broadly, the reasons why, in these competitive times, the poor work against each other and have little capacity for collective action. While the Annawadi described by Boo is brimming with individual enterprise, courage, and resilience, there is little indication of meaningful political engagement and organized resistance. Mumbai is renowned for its vigorous housing rights movements, sex workers’ unions, and small vendors’ associations. It is astonishing that in an otherwise insightful book about a slum in this vibrant city, we find no examples of successful collective action, either among the residents of Annawadi or between the residents of Annawadi and the world outside. Such an absence makes this “single, unexceptional slum” seem exceptional indeed.

One may argue, of course, that a single book can never do everything, that the responsibilities of an individual author are limited. Yet the subject matter of Behind the Beautiful Forevers, along with the recognition it has received, should push us to be more demanding. Boo’s work is part of a larger genre of films and writings on the urban poor that has exploded in popularity in the last decade, in India and beyond. While there are many reasons for the proliferation of such works, a central one, surely, is their relative ease of production. It is not difficult or expensive to obtain access to the poor. There are no razor-wired fences and gun-toting guards to contend with. One need not bother with bribing maids or hacking laptops. (In contrast, how much do we know about the bed-hopping, drug-snorting, and verbally abusive ways of the rich—forms of anti-social behavior that are ubiquitous among Annawadians, according to Boo? What we do know, moreover, is not due to assiduous videotaping, interviewing, and rummaging through public records, but to semi-autobiographical observations and other brittle sources that can rarely lay much claim to authenticity.) In many ways, the lives of the poor, especially the urban poor, are already an open story, penetrated, dissected, and acted upon by government officials, global charities, journalists, and even “slum tourism” operators. Indeed, this ease of access to the marginalized should enlarge the scale of responsibility of anyone writing on the subject, especially when the author is as insistent, as is Boo, about the fastidiousness of her research. A special measure of care should be taken to ensure that depictions are representative, and that possible omissions are noted.

Boo’s book, to be fair, is a cut above the standard fare on the subject. There is a good deal to be learned from Behind the Beautiful Forevers and its rare micro-view of the slum. Readers may never see “Ribby children with flies in their eyes” in the same light again, and may be pushed to care more about a waiter’s meager wages than whether he served their soup on time. These are certainly possibilities. But there is another, less laudable possibility: that the neoliberal establishment will find substance in Boo’s book for their wider narrative that the government can only ever fail, and that retracting the already-thin cover of publicly funded programs remains the best bet for getting India back on track.

Mitu Sengupta is associate Professor of Politics, Ryerson University, Toronto, and Director of the Center for Development and Human Rights in New Delhi. An early version of this article appeared in the blog www.kafila.org.

Photo: slum in Mumbai, taken in 2010 by cactusbones (via Flickr creative commons)