Slouching Toward Jerusalem, Riyadh, and Washington To Be Born: A Conversation with Khaled Abou El Fadl on the Trials of Egyptian Democracy

Slouching Toward Jerusalem, Riyadh, and Washington To Be Born: A Conversation with Khaled Abou El Fadl on the Trials of Egyptian Democracy

F.G. Mohamed: Egyptian Democracy?

Khaled Abou El Fadl is the Omar and Azmeralda Alfi Professor of Law at UCLA and an internationally recognized expert in Islamic law and human rights. Since the ouster of Hosni Mubarak, he has consulted regularly with leading members of Egypt’s judiciary on constitutional issues. He is the author of numerous books, including his decorated The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from Extremists and most recently Islam and the Challenge of Democracy, co-authored with Joshua Cohen and Deborah Chasman.

Khaled Abou El Fadl is the Omar and Azmeralda Alfi Professor of Law at UCLA and an internationally recognized expert in Islamic law and human rights. Since the ouster of Hosni Mubarak, he has consulted regularly with leading members of Egypt’s judiciary on constitutional issues. He is the author of numerous books, including his decorated The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from Extremists and most recently Islam and the Challenge of Democracy, co-authored with Joshua Cohen and Deborah Chasman.

We spoke on June 28, after two weeks that were tumultuous even by the standards of post-revolutionary Egypt: an elected parliament dissolved, a seizure of power amounting to a “soft coup” by the military council, a run-off election that soon turned into a stand-off between the military and the Muslim Brotherhood, and all before Mohamed Morsi of the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party was declared Egypt’s first freely elected president.

Khaled Abou El Fadl and I discussed the role the courts played in these events, the foreign pressures weighing on the military council, the workings of a neoliberal colonial army, and the future of political Islam in the wake of the Arab Spring. His remarks have been confirmed by many of the facts now emerging on the military council’s unilateral passage of a national budget and the relationship between the military council and the Supreme Constitutional Court, and they shed light on the current battle over Morsi’s reinstatement of parliament, which reconvened long enough only to initiate an appeal of the court’s invalidation of the December parliamentary elections.

FM: Let’s begin with the Supreme Constitutional Court’s June 12 decision, which declared December’s parliamentary elections unconstitutional and paved the way for the military council to dissolve parliament and regain full political control in Egypt—at the very moment when they had promised a handover to civilian authorities. When you heard of what the court had done, did it strike you as a valid legal decision or as pure politics?

KAF: I wasn’t surprised, but let me fill in some details. The legal background is that the language of the regulations for conducting parliamentary elections issued by the military council was not tight and left a lot of gaps and a lot of problems. After the elections, someone who had lost in one of the districts brought a complaint arguing that two-thirds of seats are supposed to go to party members and one-third to individual members, to independents. This fellow complained that that the regulations allowed the parties to have their members run as individuals. And that is a problem in the electoral law, which should have made clear that you need truly to be an independent. The issue is not just to be running individually, but to give non-party people the opportunity to fill a third of the parliament.

Like everything the military council has issued since it has come to power, the election rules would give pause to a proficient lawyer, or someone who knows how it’s supposed to be done. But in this case their regulations weren’t the only issue, and I want to emphasize this: several meetings took place between the military council and the heads of the parties before the parliamentary election rules were issued, with members of the judiciary including the head of the Egyptian constitutional court in attendance. They all signed off on the language of the electoral law that the supreme court later knocked down.

When this fellow brought his lawsuit, the case was put on the fast track to the Egyptian supreme court. Usually these cases have to go through hurdles of administrative courts and appeals. The exact question before the court was whether the election should be re-run in this individual’s district. But the court issued a decision in two parts, one stating that the language of the electoral law is unconstitutional and the other stating that because the one-third is unconstitutional the whole election is unconstitutional.

What is the precedent? There have been several Egyptian supreme court decisions that declared exactly the same issue to be unconstitutional. In the 1980s and again in the ‘90s, the typical scenario was that members of the ruling party would run in the elections as independents, and as soon as they won they would announce that they were joining Al-Hizb al-Watany [the ruling National Democratic Party]. Sometimes when the Ikhwan [Muslim Brothers] did well in the elections, they would run as independents, because they couldn’t run as members of a party, and then the government itself would try to invalidate the person’s election.

In the past, however, the court showed far more restraint in saying that you cannot exploit the seats for independents to further the interests of parties and did not declare whole elections invalid. They did so once under Mubarak, but justified the decision because a great many violations occurred.

In other words, what is rather odd here is, first, that the issue was fast-tracked; second, that the head of the supreme court played a role in drafting the electoral laws with the military council and parties and at the time raised no objections to the language; and third, that the supreme court could simply have left it with the administrative courts, which could have invalidated the elections in just this fellow’s district and ordered a new election for that seat. If the supreme court wanted to make a point that this is unconstitutional, they could have invalidated the one-third alone.

The supreme court’s decision came in a long opinion. In language we are not accustomed to, it goes on about how the supreme court needs to protect democracy and is a bulwark against authoritarianism, and about how this system of two-thirds and one-third is there to guarantee the rights of individuals to equal access to parliament. The way I read this is that they know they are about to do something rather sweeping and unusual given their own precedents, and so they have a lot of what we would call in American law “dicta” about democracy and why they cannot decide this case narrowly but must deal with the larger issues.

There are a couple of other things to consider. Normally when you decide that a parliament is unconstitutional, you hand the decision back to parliament and say, “OK, organize a new election.” But some members of the military council jumped on the decision and canceled the parliament without any clear motivation. It was the military council that drafted the electoral law that turned out to be unconstitutional, and the military council that now wants to play the magistrative role of drafting new electoral laws. So it’s quite a mess.

The military council was not surprised that the Ikhwan had won the most seats in the parliament. But as presidential elections approached, the military council postponed them as long as they could. The idea of having their own man in the elections whom they would back up very strongly, Shafiq, had formed, and they exerted pressure on the elections committee not to disqualify Shafiq although there are thirty-five corruption charges pending against him. In theory at least, he could be elected and then convicted, though of course they were counting on the fact that once he became president he would have immunity and you wouldn’t be able to touch him.

Why did the Egyptian supreme court issue this decision at this time and in this fashion? What I know is that the military council, right before the elections, when it was backing up Shafiq with all of its might, was confronting a lot of foreign pressure to make sure that certain conditions and situations in Egypt did not change—not just Camp David [the 1978 peace accords between Israel and Egypt], but the oil agreement with Israel, which is a windfall for Israelis. There was a lot of anxiety about Islamists coming to power.

FM: When you say “foreign pressure,” I imagine you mean American pressure?

KAF: American, Saudi, and Israeli. These were the ones who exerted the greatest pressure on the military council, basically saying you can do whatever you want in Egypt, but here are vital interests that the army must guarantee for us. The army is the one that is responsible for guaranteeing these interests. That’s why, for instance, the military council insisted that you can’t go to war without the approval of the military. This was a direct message to Israel and the United States: “Don’t worry, not that much is going to change in terms of your interests.” Another one of the pressures or demands had to do with their substantial financial investments in Egypt. They don’t want a government that’s going to nationalize or otherwise attack agriculture law, or modify the contracts that are the basis of a lot of these investments, because that would cost both Saudis and Americans billions of dollars.

This is what the military council refers to as “high national interests” or “sovereign interests.” It’s all cover language for really important things that we don’t trust to civilians because civilians might make autonomous decisions. At least in their world, there persists the idea that the army is the backbone of the country and there to protect Egypt, but at the same time it is part of the military’s firm doctrine that they should never go to war with Israel. It’s an army that consumes one-quarter of the national budget, but in which none of the officers ever expects to fight. They’re now taught business and business law courses in military school, because the army runs a financial empire. It’s an interesting concept: an army that has vowed never to fight—not, of course, that I’m arguing for war.

FM: I think I understand what you’re saying. The army’s attempts to become a state-within-a-state do not reflect the intentions of the army alone, but also its role as salaried guardian of foreign interests.

KAF: Yes, absolutely. This leads me back to the supreme court decision. The military council spoke to the chief justice, who remember was present when these electoral rules were drafted. Along with a couple of other justices in the Egyptian courts, he has a good relationship with the military council; they are always invited to the special meetings, they talk to each other. It’s not like the image of a Supreme Court justice in the United States, who is isolated from the world—even though that myth needs to be exploded: though some justices liked to be isolated, [former Chief Justice] Rehnquist was at cocktail parties with politicians all the time. The Egyptian supreme court shows a lot of independence but at the same time they are careful not to rock the boat so much as to cause a complete showdown, and that’s part of their legal culture.

In this particular decision, the military council gave the supreme court a doomsday scenario. They didn’t tell the court that they were backing Shafiq and that he was going to win. Rather, they said that there is a good chance that the Ikhwan are going to win: the elections are being observed by a lot of outside parties and the judiciary, so our hands are tied. And if the Islamists win the presidency and control the parliament, this country is going to collapse, Saudi and American investors are going to run away—and here they pointed to the stock market, which happened to lose a lot of points when it was reported that the Ikhwani person was likely to win. Egypt, they said, is in danger of becoming another Iran or worse—or, we’re really worried about the Israelis invading.

The members of the military council are horrible administrators but have been remarkably cunning in the way they’ve run things since coming to power: they’ve been manipulative and dishonest, they promise things and then they go back on them, and so on. The supreme court sped up the decision because they thought that they were dealing with an issue of the highest national security interest. Then the justices, knowing the army (which had set the rules) would like to dissolve the parliament, decided that there was in fact a flaw, so they went ahead and dissolved the parliament. Since the decision has come out, I have heard some justices say nasty things about the military council, that they turned out to be snakes as usual.

What the army tells you when you sit with them is that they have pressures. In our countries, unfortunately, when you say, “we have pressures,” it’s never domestic. The United States says democracy is fine, but the Egyptian army has to guarantee the security of Israel, and this democracy cannot result in an unsafe situation for Israel. Democracy is fine, but you can’t touch Camp David. Democracy is fine, but you can’t touch Israel’s oil deal. Democracy is fine, but if you lift the blockade on Gaza—on this I was surprised, I thought they would have some leeway—we’re not responsible if Israel decides to strike you, and then you’re going to be in a very uncomfortable position: you’ll have to strike back against Israel or take the insult, but striking back against Israel will mean the destruction of the army and its privileges. And so on.

FM: In other words, democracy is fine so long as you do everything Mubarak was doing for us.

KAF: Actually, that’s a pretty good sum of it.

FM: Egypt’s gas deal with Israel, which furnishes some 40 percent of the latter’s supply while Egyptians endure chronic gas shortages, has been a sore point for some time, and was often cited during the revolution as one of the failures of the Mubarak regime. Last I had read the natural gas corporation had stopped exporting to Israel. Has that changed? Am I mistaken?

KAF: They had announced this, but I have asked several of the engineers and they said it’s not true, the shipments continue. According to the information I have, this was just a cover story. The engineers said that if there was an intention to do something serious about the gas deal, you’d see Israel and Egypt actually renegotiating the price. Instead it’s back to the Mubarak paradigm where you tell the people one thing and do another—like keeping the provisions of Camp David secret from the Egyptian people. I know several participants in civil society—not necessarily just Islamists but also liberals—who are extremely unhappy about this. On a whole host of issues related to national affairs and national security, the military council more or less tells civilians, “It’s none of your business, you guys will mess up things,” like they’ve been doing such a marvelous job these past years.

The other issue worth mentioning is the budget. When they were talking to the supreme court, military council members made it sound as though the world would end if the parliament put together the budget, because these people are going to get into all sorts of things that will have severe repercussions. The military council and the Ministry of Interior ended up making the budget, and it turned out to be Mubarak’s budget all over again. Education, for instance, was minimally funded and public works received practically nothing—the same old corruption.

FM: So this is not just the military budget but the entire budget?

KAF: The whole budget. Everything. They used the fact that the parliament was dissolved as an excuse for drawing up the budget. They set the budget and then in their constitutional declarations—or what I call the unconstitutional declarations—stated that the new president cannot touch the budget. Which is like saying to the new president, “Here’s the presidency, but you cannot change any of the rules that would actually enable you to do anything in the country.”

This is why some of the justices of the supreme court thought that they had been tricked, because the military dissolved the parliament and then put in unchallenged the same financial privileges that it enjoyed under Mubarak. It is shameful, because in a country like Egypt [with over 80 million people] you have less than a billion dollars for education, and you have a very nominal amount for technological development, I think two million dollars. It’s a joke.

FM: If the judiciary felt slightly blindsided, is the recent decision of the Supreme Administrative Court, which prevents the military from making civilian arrests, perhaps a strike back?

KAF: Yes, that’s how I understood the decision from the administrative court. The military has now been arresting people since January 25. The number of people who have been detained, or tried by tribunals, or imprisoned by the military is astounding. I was told by a friend of the chief justice that the chief justice thought that the military council had damaged the reputation of the supreme court and the judiciary, and he was very unhappy. And I don’t think it’s going to be reversed. The way the military council handled this whole situation was extremely disrespectful to the judicial branch, which basically felt lied to, and cheated, and tricked.

FM: Might that decision on civilian arrests have the unintended consequence of empowering the security forces and the interior ministry? If the military can’t make civilian arrests and someone has to do so, then the security forces will be only too eager.

KAF: Yes, but the security forces already have that power. The parliament never got the chance to change the laws that more or less allow the security forces to arrest anyone, detain them, and prevent access to them, creating conditions that are inherently abusive. The laws that allow the security forces basically to hold themselves accountable, which means that they aren’t accountable at all, are still intact.

FM: Let’s try to find some sort of silver lining in all of this. It seems as though parliamentary elections will have to be called at some point, probably in the near future. Might this give the secular Left more time to organize this time around? Hamdeen Sabbahi, who did surprisingly well in the presidential election, has been talking about organizing a political party. In the long run could dissolving parliament be either neutral or positive?

KAF: I think yes. Shafiq has said, yes we lost the presidency but we are going to bring something like Al-Hizb al-Watany to compete in the parliamentary elections. I don’t think that scenario will play out, given the mood in Egypt. I don’t believe in the staying power of Shafiq, who was a complete invention of the military council. Those who supported him imagined that they were restoring stability and safety. They were sick of crime and sick of civil unrest.

Every time I go to Egypt, I get the feeling that a lot of Egyptians are uncomfortable with the idea of one party controlling both the presidency and the parliament. I was in Egypt the day people were casting their votes, and I couldn’t believe how many people would say we’re going to vote for Shafiq just because the Ikhwan had the parliament. Egyptians don’t want the parliament and the president to start passing laws requiring them to wear a hijab and things like that.

The invalidation of parliament makes room for people like Hamdeen Sabbahi, who I think would be very good for Egypt, or perhaps Mohamed ElBaradei, though I’m not sure what his plans are. Such people have gained two things: they have more time to organize, and they’ve learned that you can’t campaign among intellectuals and university students—what percentage of the Egyptian population is that?—and think that it’s going to be enough to win.

So I think there might be an accidental benefit that comes out of it, although the military council has played a very devilish role, especially [Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein] Tantawi.

FM: One final and more general question, on the kind of political Islam that you see emerging in Egypt and other countries of the Arab Spring. Can Egypt strike out in the direction of a modern, democratic political Islam, or is the influence of the Gulf too strong?

KAF: I’m generally optimistic. These battles over the soul, or the theology, or the intellectual heritage of a tradition, whether it is Christianity, or Judaism, or Islam, or whatever, often take periods to develop, but we can identify good indicators and bad indicators.

What’s good in this situation is, first, that Saudi Arabia had initially done everything possible to prevent the sentencing of Mubarak, threatening to withdraw all investments in Egypt if Mubarak was tried. Second, Saudi Arabia really backed the Jama’a al-Islamiya. These folks, who are truly Wahhabi, are their favorites. You’re going to see a lot of tension and friction forcing the Ikhwan to distinguish themselves from the Wahhabi and Salafi types. I think they’re going to draw closer to the model of [Tunisia’s] Ghannoushi and the Islamist party in Turkey. Among the Ikhwan themselves, no one is in any mood to talk about whether music is halal or haram, or whether women should be banned from this or that, or any of that social stuff, while the Jama’a al-Islamiya are fantasizing about it. I think ultimately the Ikhwan are going to be forced away from the Wahhabis. It’s very difficult to work with the Wahhabis or live with the Wahhabis long term, because they lack flexibility in their thought.

Another positive indicator: I was surprised in this whole process by how very few Egyptians even contemplated the idea of living in a state resembling the Iranian or Saudi model. Those who voted for the Ikhwan believe that personal piety might make people less corrupt, but I haven’t encountered any substantial numbers who say, “We vote for the Ikhwan because they will rule in the name of God and apply God’s law, which is infallible.” I definitely think the whole experience in Tunisia, Egypt, and Syria is about a return to authenticity, in the sense that no one is denying their Islamic identity. But at the same time they are restructuring that identity in a way that is entirely consistent with democratic ideas. It’s remarkable to me how many mosques I attended in Egypt where the sheikh would say, “God has given you the right to decide who will rule you, and no one can take that away.” That has to be positive. It’s very different from the years I spent in Kuwait or Saudi Arabia, where you were basically told that you have to obey the ruler even if he beats you or oppresses you. It’s a really different discourse, so I’m optimistic.

I think the real issue is the military and foreign intervention. This is not the first constitutional awakening in this part of the world. There have been several in the past, bringing with them some quite enlightened ideas, and every time foreign intervention aborts the project. But it’s going to be different this time, because of the level of education and because of the modern means of exchanging information, which provide multiple sources so that no one relies on state TV. It’s not going to be easy just to control and steer people, as in the past.

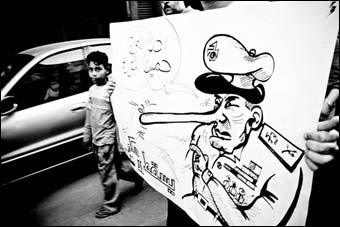

Photo: anti-military council poster, by Maggie Osama, 2011, via Flickr creative commons