Saving Affirmative Action from Itself

Saving Affirmative Action from Itself

N. Mills: Saving Affirm- ative Action

THESE DAYS the future of affirmative action in higher education is in jeopardy. A series of states—among them Michigan, California, Florida, Nebraska, and Arizona—have banned the consideration of race, ethnicity, or gender by any unit of state government, including public colleges and universities. As a result, state-run institutions of higher education with the greatest capacity for accepting minorities are increasingly less able to do so.

THESE DAYS the future of affirmative action in higher education is in jeopardy. A series of states—among them Michigan, California, Florida, Nebraska, and Arizona—have banned the consideration of race, ethnicity, or gender by any unit of state government, including public colleges and universities. As a result, state-run institutions of higher education with the greatest capacity for accepting minorities are increasingly less able to do so.

Nor can these institutions turn to the public for support on affirmative action. By a 55-to-36 percent margin voters believe affirmative action should be abolished altogether, and by a 61-to-33 percent margin they oppose affirmative action for blacks in hiring, promotion, and college entry, according to a 2009 Quinnipiac University poll.

This negative view of affirmative action in higher education can, in part, be explained by the rightward shift of the country since 1980 and the pressures the current recession has put on state budgets. But even more important is the way in which affirmative action has strayed from its 1960s roots and lost sight of its own history.

Today, the only way affirmative action in higher education can save itself from losing still more public support is for it to become far more inclusive in practice. It needs to reach high-school students who for a variety of reasons—not just because of their race or ethnicity—have been disadvantaged in the struggle to get into college.

Lyndon Johnson’s Breakthrough

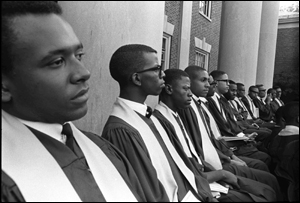

The link between affirmative action and race was first made in 1961 by President John Kennedy, when he signed Executive Order 1025 requiring contractors doing business with the federal government to take “affirmative action” to ensure that their workers would be hired without regard to race, creed, color, or national origin. But the justification for affirmative action as we know it was established four years later by President Lyndon Johnson in a breakthrough speech that he gave at Howard University’s 1965 commencement.

At the heart of Johnson’s speech, which was principally the work of former Kennedy speechwriter Richard Goodwin, lay the idea that the passage of civil rights legislation had not put whites and blacks on equal footing when it came to competing for places in society. The vestiges of segregation and the dual-school systems of the South remained. “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘you are free to compete with all others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair,” Johnson declared.

The task before the country, Johnson went on to say, was to create opportunity for black Americans in fact, not merely in theory. To that end he promised that the federal government would work on a series of fronts, from job training to health care, “to give 20 million Negroes the same chance as every other American.” The result was a clear-cut strategy for helping those suffering from America’s historic racism that could be applied to a variety of institutions.

When it came to higher education in the North, there was, however, a problem in the affirmative action remedies that Johnson proposed in his Howard University speech. The institutions in question were ones in which there had never been a legal finding of discrimination. The only lawful way for these institutions to grant preferences to minority applicants, whose grades and test scores so often fell below those of whites, was for the courts to develop a new legal basis for affirmative action: diversity.

The Supreme Court and Diversity

Diversity first became a crucial legal concept in the 1978 case University of California Regents v. Bakke. Allan Bakke, a white applicant to the medical school of the University of California at Davis, contended that he had been discriminated against because Davis’s program reserved sixteen of the 100 places in each year’s class for minorities. The Court agreed with Bakke, who had higher test scores than a number of the accepted minority applicants, and ordered the medical school to admit him. But the Court also made a second ruling in the case, declaring that race-conscious admissions programs, provided they operated without a fixed goal or percentage in selecting minority students, fell within the law.

The key opinion in Bakke was that of Justice Lewis Powell, who cast the swing vote in both rulings. The “attainment of a diverse student body” was, Powell wrote, “constitutionally permissible” and served the government’s interest. Institutions of higher learning, he went on to say, had historically been given the right to use their own judgment in selecting their student body, and they were therefore protected by the First Amendment. The key to a successful diversity program, Powell argued, was applying holistic standards to every student considered for admission. As an example of what he had in mind, Powell cited Harvard, which had made its undergraduate diversity program work by treating race as a “plus” among a variety of criteria it used to admit students. Other colleges and universities, Powell implied, had only to follow Harvard’s precedent to be in compliance with the law.

In 2003, the Supreme Court put the Bakke rulings on even solider ground when it decided two University of Michigan cases, Gratz v. Bollinger and Grutter v. Bollinger. In Gratz v. Bollinger, by a 6-to-3 margin, the Court ruled unconstitutional the University of Michigan’s practice of automatically awarding all undergraduate, minority applicants twenty points on their admission forms (100 were needed to get in). Like the sixteen of 100 places reserved for minorities in Davis’s medical school, the twenty points given minority applicants constituted a rigid quota, the Court held in a decision written by Chief Justice William Rehnquist. In Grutter v. Bollinger the Court, on the other hand, ruled in favor of the University of Michigan Law School’s practice of making the minority status of an applicant a “plus,” because the “plus” was accompanied by the use of a broad set of admission criteria.

The standards Justice Powell had put forward in support of affirmative action in Bakke were affirmed by the 5-to-4 decision. The Court fully endorsed Powell’s belief that achieving diversity in high education was a compelling state interest; colleges and universities working to achieve that end were, the majority said, protected by the First Amendment, provided they took steps to limit the damage done to students who constituted innocent third parties.

This proviso meant that in practice any affirmative action plan had to be narrowly tailored. Its focus had to be on increasing the diversity of a college or university student body. Preferences could not be given with the intention of reducing the historic deficit of disfavored minorities in higher education or as a remedy for societal discrimination.

The Michigan cases were landmark rulings, but in contrast to the historic Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954, in which the Court unanimously overturned the concept of separate but equal, the Court in 2003 was uneasy about what it had decided. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who wrote the majority opinion in the Grutter case, went out of her way to qualify what she had written. Instead of speaking as if she and the justices who sided with her had established a lasting precedent, O’Connor concluded her opinion by observing that “race-conscious admissions policies must be limited in time.” All “racial classifications, however compelling their goals, are potentially so dangerous that they may be employed no more broadly than the interest demands,” Justice O’Connor warned. Twenty-five years, Justice O’Connor declared, was as long as she expected the racial preferences sanctioned in Grutter to be needed.

Backlash

Michigan voters reacted angrily to the Court’s rulings. In 2006, by a whopping 58-to-42 percent margin, they passed the Michigan Civil Rights Initiative, which amended the Michigan constitution to prohibit state agencies and institutions from using affirmative action programs based on race, color, ethnicity, national origin, or gender. Behind the Michigan voters’ response was certainly racial resentment, but it is a mistake to think, especially in the midst of the current recession, that the backlash to affirmative action in Michigan and elsewhere is limited to bigots.

Who in higher education benefits from affirmative action and who is left in the cold has changed dramatically since Lyndon Johnson spoke at Howard University in 1965. Behind Johnson’s affirmative action proposals was the argument that black Americans were being singled out for help because they had been victimized by the country. African Americans, as Johnson put it, had been “deprived of freedom, crippled by hatred.” Johnson’s metaphor of the runner who has been hobbled by chains and is vainly trying to compete showed how fully he had America’s slave and Jim Crow history in mind.

Who in higher education benefits from affirmative action and who is left in the cold has changed dramatically since Lyndon Johnson spoke at Howard University in 1965. Behind Johnson’s affirmative action proposals was the argument that black Americans were being singled out for help because they had been victimized by the country. African Americans, as Johnson put it, had been “deprived of freedom, crippled by hatred.” Johnson’s metaphor of the runner who has been hobbled by chains and is vainly trying to compete showed how fully he had America’s slave and Jim Crow history in mind.

The implementation of the Bakke and Grutter decisions has, by contrast, frequently lacked both a moral basis and the Supreme Court’s sense of restraint. The carefully calibrated “plus” that Justice Powell spoke of racial and ethnic minorities getting has become far more than a mere “plus” in practice. In No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal, the most important study to date of race and class in college admissions, Thomas Espenshade and Alexandria Walton Radford point out that for black and Hispanic minorities preferences are large and significant rather than mere tipping mechanisms. Using data from the 1997 SAT college admissions exam, they came up with a startling discovery. Private colleges and universities gave blacks an overall admissions bonus of 310 points and Hispanics an extra 130 points, out of a possible score of 1600 points. Conversely, Asian applicants were penalized 140 points in the admissions game.

In addition, many of the black students receiving the 310 point admissions bonus were not from families that were ever the victims of slavery or Jim Crow. As William Chace, a strong defender of affirmative action and the former president of Wesleyan University and Emory University, observed in a recent essay in the American Scholar, affirmative action now turns out to be helping a considerable number of black students “who have suffered the wounds of old-fashioned American racism little or not at all.”

This issue of who should benefit from affirmative action came up in 2004 at a controversial meeting of Harvard’s black alumni. There it was pointed out that only about a third of Harvard’s black students were from families in which all four grandparents were born in America and descendants of slaves. Other studies have shown that Harvard is not unique in the preferences it gives to black immigrants or the children of black immigrants. More than a quarter of the black students enrolled at America’s selective colleges and universities are immigrants or the children of immigrants, and at schools such as Columbia, Princeton, and Yale, two-fifths of admitted black students are of immigrant origin.

But even among students who come from families that were once the victims of America’s historic racism, the rewarding of affirmative action benefits has been problematic. In Lyndon Johnson’s Howard speech, the runners receiving the extra help are those still suffering from the vestiges of slavery and segregation. They are not those who by skill and by circumstance are now able to compete. The irony in higher education is that those unable to compete—typically students from poor, inner-city schools—are all too frequently the ones affirmative action has ignored. These students are too far behind educationally for affirmative action to help them. Instead, time and again the minority students benefiting from affirmative action come from middle-class families and attended good public and private schools.

Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson explained this phenomenon by pointing out that “affirmative action programs are not really designed to address the problems of poor people of color,” but in the real world such a defense of affirmative action won’t cut it. Especially for the sons and daughters of poor and working-class white families, affirmative action preferences as they now exist have stirred enormous resentment. These students have seen affirmative action benefits go not only to students who were never the victims of America’s historic racism but students who are often wealthier and better educated than them. The message these white students have gotten is that their problems don’t really count in the eyes of affirmative action’s liberal defenders.

Such feelings are not paranoid. As Espenshade and Radford note, “The admission preference accorded to low-income students appears to be reserved largely for nonwhite students.” The nation’s best private colleges believe they have enough general access to whites, and so when it comes to investing in disadvantaged students the colleges are motivated by the fact that nonwhites give them what whites cannot—a boost in their multicultural statistics and, by extension, better ratings in influential publications such as U.S. News & World Report.

Nobody is more aware of these calculations than today’s high-school students, who currently have every incentive to game the college admissions system. In a recent front-page story, “On College Forms, A Question of Race, or Races, Can Perplex,” the New York Times featured a Maryland high-school student with a black father and an Asian mother who faced the dilemma of how to define herself in applying for college. “It pains me to say this, but putting down black might help my admissions chances and putting down Asian might hurt it,” the student observed. For her, it was clear that when it came to getting into the college of her choice, her true advantages and disadvantages were not as important as the category into which college admissions officers could place her.

Helping the Truly Vulnerable

The result is an affirmative action crisis that, if nothing is done about it, promises to get worse. Doing away with affirmative action entirely and leaving our colleges and universities white and Asian-American enclaves is unthinkable, but so, too, is continuing an affirmative action system increasingly weakened by the broad political opposition it generates and by the fact that it often benefits students with no historical basis for claiming special preferences.

The good news is that between these two poles lies a compelling alternative: make sure that, in theory and in practice, affirmative action has the same moral basis today that it did when Lyndon Johnson spoke at Howard University. In Barack Obama we have a president who understands and defends the kind of moral distinctions that were part of Johnson’s Howard speech. When asked by ABC News’s George Stephanopoulos if his daughters should benefit from affirmative action, Obama, a supporter of affirmative action, replied, “I think that my daughters should probably be treated by any admissions officer as folks who are pretty advantaged.” He then went on to say, “I think we should take into account white kids who have been disadvantaged and have grown up in poverty and shown themselves to have what it takes to succeed.”

In the affirmative action that presidents Johnson and Obama describe, fairness, rather than mere diversity, is the goal. To give affirmative action a realistic future, we need only to extend their logic. In the coming years the aim of affirmative action preferences should be to give sympathetic treatment to all students who have started out in life with disadvantages—whether caused by race, poverty, ethnicity, family, or any other sources for which they cannot be held accountable.

The Supreme Court has already sanctioned taking such an approach to affirmative action. In Bakke Justice Powell described the need to see diversity in terms that both included and went beyond race and ethnicity. “The diversity that furthers a compelling state interest encompasses a far broader array of qualifications and characteristics of which racial or ethnic origin is but a single though important element,” he declared in an observation that Justice O’Connor quoted in writing her majority opinion in Grutter. The advantage of such a broad definition of affirmative action is that it avoids implying, as is now frequently the case, that the disadvantages suffered by some college applicants are worthy of our sympathy while those of others are just tough luck.

Today, just 3 percent of the students enrolled in our most academically selective colleges come from the bottom quarter of the socioeconomic scale, and therein lies the source of much of the resentment that many poor, white families feel toward affirmative action. A broadly conceived vision of affirmative action has the capacity to reduce such resentment. It enlarges the constituency with a stake in affirmative action, and in so doing strengthens the coalition affirmative action needs to withstand the hard times that lie ahead.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Like a Holy Crusade: Mississippi 1964 and Debating Affirmative Action: Race, Gender, Ethnicity, and the Politics of Inclusion.

Photographs taken by Yoichi Okamoto at President Johnson’s Howard University commencement speech