Deadly Games

Deadly Games

In the spectacularly violent world of Squid Game, exploitation and brutality are built on the illusion of choice.

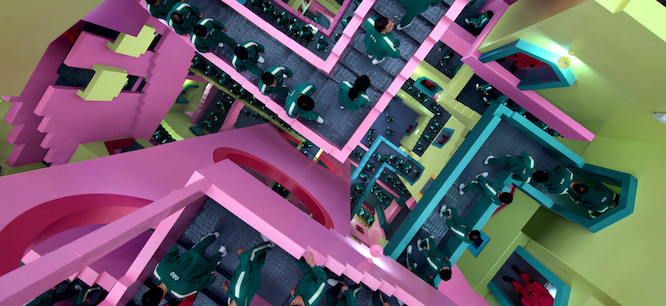

Squid Game, the South Korean Netflix series that has become the streaming platform’s most-watched show of all time, takes place in a grim fantasy setting burrowed within a relatively unaltered version of our own reality. In the show, 456 deeply indebted participants compete in a secret series of children’s games to win a portion of a pot of 45.6 billion won (roughly $38 million). Losing a game means death; the fewer players left at the end, the more money each player wins, incentivizing murder. The participants give a limited form of consent to the rules of the games—they are unaware of the deadly stakes when they join but are swayed to continue by the money at stake—and a simple majority vote among the players will allow them to stop the game and leave (though any individual who attempts to escape alone is executed). It is this element of financially constrained choice that sets Squid Game apart from similarly dystopian deadly competitions like The Hunger Games.

Squid Game is the latest in a series of popular fictional depictions of class conflict in the past decade. The show makes no mystery of its political themes. The protagonists are primarily working-class people who have been backed into a corner. They may have their weaknesses, like the main character Seong Gi-hun’s (Lee Jung-jae) gambling habit, but writer-director Hwang Dong-hyuk goes out of his way to make clear that Seong’s real troubles began after his factory was shut down following the violent repression of a strike. Another character, Abdul Ali (Anupam Tripathi), is an undocumented worker from Pakistan who is essentially forced into the game after his wages are stolen by his boss. While some of the contestants, like the gangster Jang Deok-su (Heo Sung-tae), are portrayed as antagonists, the real villains of the show are a masked wealthy elite who bet on the players and the armed enforcers hired to police the game. The game masters actively encourage the players to turn on another. They set the terms of the contest, which they profess is untainted by the discrimination and unfairness found in the outside world, but they also represent the economic system that forced the players into the games in the first place. It’s little wonder that the show has resonated so strongly after a global pandemic in which many faced the very real choice to either risk their lives working or to sink deeper into poverty and debt.

While the creators of the competition are eager to pit the players against one another, the characters do come together to vote to leave the game at one point. But when faced with harsh realities at home, over 90 percent of the players decide to return to the game for their chance to escape a life of misery, no matter how unlikely or traumatizing—or fatal—the process might be. Opting out of the competition means giving up their lottery ticket. While the stakes of the game are heightened, Hwang believes that the abundance of false choices under crushing conditions in the real world is key to why the show has been so successful. In a recent interview with the Korea Times, he argued that “the world has changed into a place where such peculiar, violent survival stories are actually welcomed. . . . The series’ games that participants go crazy over align with people’s desires to hit the jackpot with things like cryptocurrency, real estate and stocks.” In the show, the accumulated prize money literally dangles above the participants’ beds in a transparent orb that lights up and emits slot-machine chirps every time another player dies.

Despite the incentive to harm other contestants—and the dawning realization that it is unlikely that more than one player will survive the final game—many of the protagonists band together. Seong creates a team of contestants that look out for each other; in one case, they build a defensive structure in their massive shared dormitory to protect themselves from attacks at night. While some contestants are willing to step over anyone’s body to reach the top, others make major sacrifices. One woman gives her life once she realizes that her new friend, North Korean defector Kang Sae-byeok (Jung Ho-yeon), has people depending on her in the world outside the game. On multiple occasions, Seong distinguishes himself with his compassion, especially in his friendship with an elderly man who stands at a disadvantage in contests that depend on physical strength. When Seong ultimately wins the contest despite his refusal to kill his final opponent, he uses the prize money to support the families of two deceased participants. And in the final scene of the show, he turns back from his flight to leave Korea to be with his young daughter so that he can fight the organization that ran the games.

Squid Game owes some of its popularity to the brutality and graphic violence that drive its plot. But responses to the show online have revealed that fans connected deeply with the characters and their struggles. The spectacle of the competition may draw viewers in, but it is our familiarity with false choices, exploitation, and the struggle to be decent under horrible conditions that has made Squid Game into a smash success.

Akin Olla is a Lead Trainer at Momentum, a social movement training institute. He is also a contributing opinion writer at the Guardian and the host of This Is the Revolution podcast.)