How Labor Learned to Love Immigration

How Labor Learned to Love Immigration

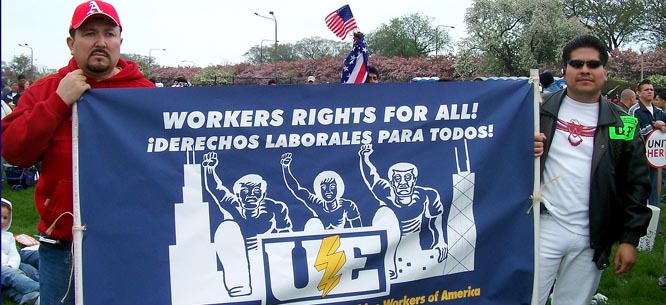

No group in America, aside from Latino activists, is a more steadfast champion of generous immigration reform than organized labor. That stance, declares the AFL-CIO, is “based on the simple idea that working people are strongest when we work together and the labor movement is strongest when we are open to all workers, regardless of where they come from.”

In recent months, union members have flocked to support rallies, while their leaders have lobbied Congress to allow the undocumented to become citizens and made an unprecedented deal with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to allow thousands of guest workers into the country. In a poll taken last December, nearly two-thirds of AFL-CIO members favored a law that would offer immigrants without papers a path to citizenship.

This is a rather stunning reversal from the policy the labor movement clung to tenaciously throughout its long history. Imagine if the Family Research Council suddenly decided to work hard for the legalization of same-sex marriage because it now believes the institution of matrimony is strongest when it is open to all Americans, regardless of whom they want to wed.

Through the nineteenth century and most of the twentieth century, unionists were nearly as consistent in their dislike of immigration as they are now in favoring it. They claimed that more foreigners, legal or not, lowered the wages and degraded the working conditions of native-born wage earners–and were less willing than the native born to risk their jobs by joining a union.

In the Gilded Age, the Knights of Labor and the AFL spearheaded the successful drive to bar any Chinese laborer from coming ashore. In California, a new state constitution drafted by the Workingmen’s Party barred Chinese residents from buying property, having access to the courts, or taking jobs in most businesses. During the long presidency of Samuel Gompers (who, as a boy, had migrated to the United States from England), the AFL backed both a literacy test for would-be newcomers and the now infamous quotas of the 1920s, which reduced immigration from the non-“Nordic” countries of Southern and Eastern Europe to almost nothing.

By the 1960s, labor had abandoned its resistance to legal immigration, as long as the numbers arriving remained modest. But most unions still viewed undocumented immigrants as incipient strikebreakers or worse. In 1973, the United Farm Workers, most of whose members were Mexican American, even set up a “wet line” along the southern border to stop undocumented migrants who might jeopardize their organizing campaigns.

The turning point came at the beginning of the new century. In 2000, the Executive Council of the AFL-CIO called for repealing employer sanctions for hiring unauthorized immigrants and a form of amnesty. What caused the change?

In part, unionists were smacked in the face by reality. The flood of unauthorized migrants seemed impossible to stop, and many of them were moving to places, like Los Angeles and Las Vegas, where impressive drives to organize Latino workers were already underway. Justice for Janitors, a project of the Service Employees International Union, demonstrated that even undocumented men and women who cleaned up downtown office buildings were eager to join a union.

Moreover, labor’s new decision-makers rarely looked or sounded anything like George Meany, the cigar-chomping foe of radical causes who presided over the AFL-CIO during its years of greatest power. An internationalist perspective came naturally to unionists who began their activist careers in the movements for civil rights, peace, or feminism. Together with the emerging generation of Latino leaders, they view legalizing the undocumented as a splendid opportunity. “For 11 million workers to know that the boss is not going to be able to intimidate them because of their immigration status,” explains Maria Elena Durazo, head of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, “It’s going to bring them out of the shadows and give them a lot more confidence and courage to stand up for their rights.” Of course, she also expects that, once these workers become citizens, they will vote for politicians the unions endorse.

Welcome as this change has been, it is hardly a magic solution to labor’s decreasing membership or weakened political clout. Passage of a decent immigration bill won’t stop employers from intimidating union organizers or force congressional Republicans to allow the National Labor Relations Board to operate normally or transform the current image of labor as a “self-interest” that loses far more often than it wins. And there are still millions of native-born wage earners, in and out of the unions, who fear—as did old Sam Gompers—that making it easier for non-citizens to get jobs makes it harder for Americans to find and improve them.

Yet a union movement that turned its back on those non-citizens would have little prospect of revival or a strong claim to moral decency in a globalized society. Working-class liberalism may sound like an oxymoron. Labor’s vigorous support for helping undocumented immigrants become citizens may alter that perception in the future.

Michael Kazin is the editor of Dissent. He thanks his colleague Joseph McCartin for his advice on this piece.