We’re All Social Democrats Now

We’re All Social Democrats Now

On the left, talk of proletarian revolution has given way to vital debates about how to enact Medicare for All and a Green New Deal, revive unionism, and strip the power of the Supreme Court.

The following is part of a series of essays, “Why I’m (Still) a Socialist,” in our Fall 2022 issue.

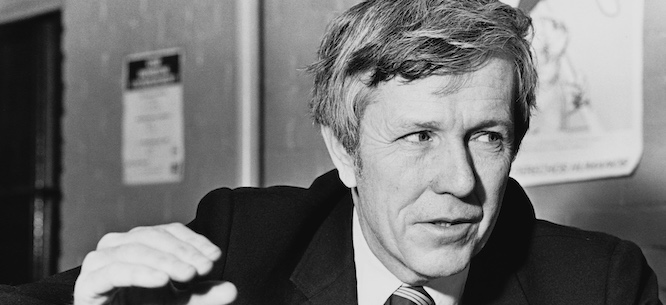

In the spring of 1973, Michael Harrington called on members of the new Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee, which he chaired, to build “the left wing of realism.” Over time, he replaced “realism” with “the possible,” but the sensibility endured. Throughout the two-century history of socialism, at least the untyrannical kind, most of its adherents have tried to balance their dream of a humane and fully egalitarian order with the need to fight for changes in the only world they would ever know.

Except for those sectarians who rant mostly to themselves, American leftists are, in their everyday practice, all social democrats now. Talk of abolishing capitalism, of proletarian revolution, and of reforms as nothing but sly tricks to make a rotten system appear fresh have given way to vital debates about how to enact Medicare for All and a Green New Deal, revive unionism, and strip the power of the Supreme Court.

True democratic socialism remains a grand and lovely vision, a secular faith that human beings can live in harmony without competing with one another for power and wealth. But no society has ever been organized that way—and the agrarian colonies that made the attempt in the nineteenth century in places like New Harmony, Indiana, and Nashoba, Tennessee, either had a short life or devolved into flawed, often authoritarian versions of their original designs. Rather than base our politics on a utopian ideal, it would be better to keep persuading our fellow Americans to nudge the country and the world closer to a point where an ethic of solidarity would have greater sway than the inhumane, individualist alternative.

So how should social democrats in the United States today define “the possible” and seek to achieve it?

First, we should recognize that big changes never occur unless large social movements pursue a patient and shrewd strategy that wins concessions from those who rule the state and economy. That is what spurred the abolition of slavery, how workers gained federal protection to form unions, how women won the vote and LGBTQ people the right to marry, and how African Americans and their allies demolished Jim Crow laws. Socialists belonged to all those movements, but they were only effective when they understood that the success of each cause mattered more than pressing their hope for a cooperative commonwealth.

Second, we should make it a priority to work for reforms that will help improve the lives of a majority of the population and can win their approval. These include higher taxes on the rich, aggressive actions to shift to renewable sources of energy, making it easier to organize unions, truly affordable and universal health provision, publicly funded child care and paid family leave, and other policies designed to turn the Constitution’s vow “to promote the general Welfare” from abstract rhetoric into enduring programs. We should also advocate reducing the military budget and oppose sending U.S. troops to fight in other people’s wars while empathizing with the women and men who choose to don a uniform and finding alternative, peaceful ways for the young to “serve the nation.”

If enacted, all these changes would do a good deal to reduce racial inequality—without compelling white people to cleanse themselves of racist sentiments, as desirable as that would be. The most politically effective way to weaken white supremacy is to promote what Heather McGhee in The Sum of Us calls a “solidarity dividend”: an expansion of access to public goods that poor Black and brown people need most but that would benefit wage-earners of all races. Back in 1966, Bayard Rustin drew up a “Freedom Budget” that would have guaranteed every citizen a job, an annual income, health coverage, good schools, and decent housing—all paid for by a tax system stripped of loopholes for the rich. Rustin counseled his fellow Black activists not to waste time trying either to soften the hearts of racists or, like Malcolm X, to scare them “into doing the right thing.” Show them how social democracy will improve their lives, and their hearts will eventually follow.

Third, we should commit ourselves to work inside the Democratic Party—to run for office at all levels, canvass for and donate to its candidates, and encourage everyone we know to get out the vote. Back in 2015, I made the case in this magazine that leftists should also be Democrats, so I won’t repeat it here. Since then, that case has only grown stronger. Bernie Sanders showed that a lifelong socialist could run two competitive races for the Democratic presidential nomination, a remarkable feat that inspired hundreds of members of the Democratic Socialists of America and other progressives to run and win elections as Democrats. With its tiny majorities in Congress, the Biden administration has been unable to enact its ambitious plans to “build back better.” But the president, a career-long centrist, embraced that agenda only because progressives in his party made it impossible for him to reject it.

For his part, Harrington urged his fellow socialists to vote and work for every Democratic presidential nominee from George McGovern in 1972 to Michael Dukakis in 1988. He had no illusions about what they could accomplish if they won (Jimmy Carter, the only who did, certainly proved that). But Harrington understood that the Democrats were the only electoral alternative to a Republican Party captured by the right. Emulate what conservatives did, he counseled in 1980, and be “as aggressive as the Goldwater-Reaganists in the long march” through the GOP.

Fourth, we have to discipline ourselves to use a political language that non-leftists understand and will be comfortable using. You can talk of “Latinx” and “BIPOC” and “birthing people” among your comrades, but realize that such terms will confuse more people we want to reach than they will comfort—and thus risk setting back the causes of racial equality, reproductive justice, and transgender rights they were coined to advance. They also make it easy for Tucker Carlson and his many fans to ridicule us as enemies of ordinary people. As the journalist Sam Adler-Bell wrote recently, the language of “‘wokeness’ . . . is hostile to the basic logic of leftist organizing. Solidarity requires an invitation, a warm and friendly offer to collude in a risky proposition. It doesn’t work as a sanctimonious entreaty to identify with an existing set of self-evident values.” Specialized language shows a disrespect for those we want and badly need to win over. We should welcome them to join a movement of peers, not a corps of language censors.

Fifth, be optimistic. Yes, a sadistic sextet dominates the Supreme Court, and it is likely that Donald Trump’s party will take over at least one house of Congress this fall and keep a stranglehold on power in half the states in the nation, despite gaining support from only a minority of voters.

Yet the ideas and programs of social democrats are more popular in the United States than at any time since the 1960s and early ’70s. Fellow realistic leftists govern most nations in South America and have increased their popularity in parts of Western and Central Europe too. The fear that our influence will grow drives much of the anxious fervor on the contemporary right, which wants desperately to “make America great again” with no clear notion of what it might mean to accomplish that impossible task.

The Indian thinker Pankaj Mishra, who usually views politics with a baleful gaze, recently told an interviewer that he felt

hopeful, because for the first time in my own lifetime, there is now an intelligentsia in Western Europe and in America that is actively engaged with the question of what left-wing politics can achieve. . . . I’ve lived through such a long period of right-wing extremism and centrist deference to it that I cannot stop being amazed and thrilled that actually, there are people who are now talking about these things we’re talking about—what socialism can achieve, what socialist ideas we should be refining in order to also deal with things like the environmental crisis.

As two young German-born leftists put it in a famous manifesto back in 1848, the task is to “represent the movement of the future in the movement of the present.”

Michael Harrington consistently spoke out for doing just that. He took seriously the need to believe in the capacity of ordinary people to take action on their own behalf—and in his own moral obligation to inspire hope. “If you consider your country capable of democratic socialism, you must do two things,” he would tell audiences. “First you must deeply love and trust your country. You must sense the dignity and humanity of the people who survive and grow within your country despite the injustices of its system. And second, you must recognize that the social vision to which you are committing yourself will never be fulfilled in your lifetime.” Carry it on. There is no other way.

Michael Kazin is co-editor emeritus of Dissent. His most recent book is What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party.