Texas’s New Ground Game

Texas’s New Ground Game

While conservatives tighten their grip on Washington, a network of grassroots organizers in three Texas cities is showing how local progressives can beat the odds. Could their efforts become a national model for opposing Trumpism?

For the past four decades, Texas has been a reliably red state. But that means that Trump’s nine-point victory last fall was less stunning and discouraging to the state’s left activists compared to the shock of Trump’s sweep in historically blue northern states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, which many Democrats had assumed were safe bets in presidential races.

Oddly, though, while conservatives tighten their grip on all three branches of federal government, it’s never been a better time to be a left-wing organizer in Texas: now the trench-warfare tactics local activists have been honing have a chance to become a national model for mobilizing the opposition to Trumpism. The Texas Organizing Project (TOP), a gritty grassroots network linking three rapidly browning cities—San Antonio, Dallas, and Houston—has fought and won enough local battles to demonstrate the value of seeding incremental progressive wins on the neighborhood level in order to build a grassroots people’s movement. And they know better than to take anything about Texas for granted.

For TOP’s communications director Mary Moreno, giving people a reason to believe voting still makes a difference in a politically predictable state starts with talking about them, not their vote.

“When we show up at people’s doors, we found that if you ask them, ‘What would you like to see changed in your neighborhood and in your community?’—that it really does help start a conversation,” said Moreno, as we drove to a union get-out-the-vote event in downtown Houston a weekend before Election Day. “Whereas if you show up with a slate of candidates, they might not be inspired,” she continued. “They might be like, ‘I don’t like politicians’. . . and they’ll shut the door. But if you ask them about issues, they always care about that. . . . It’s like they’ve been waiting for someone to ask them, ‘What would you like to see changed?'”

Despite Texas’s history as a fortress of conservatism, Houston organizers have been building a progressive local base through street-level advocacy. In last year’s demographically and ideologically polarized election season, they presented a fresh opposition to a political atmosphere rife with racial invective and media spectacle.

TOP launched in 2009 as a grassroots operation, inspired by ACORN’s Alinskyite community-organizing model, to build localized power in underrepresented, working-class black and Latino communities. Over the years, through its three city branches, the group has built a support base of more than 120,000 people across Texas. A staff of a few dozen has campaigned alongside unions and neighborhood groups on affordable housing and fair wage campaigns; protested for criminal justice reform with the national coalition, Color of Change and the local chapter of Black Lives Matter; and advocated for immigrant-friendly local ID cards for undocumented youth and parents threatened with deportation, and the transgender migrant community. For the election, TOP partnered with voter outreach initiatives of local unions and Latino community groups in order to secure allies in local office.

As Election Day approached, TOP’s three branches canvassed hard in districts known for low turnout through home visits, phone banking, and by offering rides to polling sites. Although nationally, Texas predictably went for Trump, the mostly black and Latino voters mobilized by TOP helped deliver its cities for Clinton, and more importantly, score its most important victories locally. In Houston’s Harris County, Kim Ogg became the first Democratic district attorney in thirty-six years; she promised to end the systematic jailing of those with low-level drug charges. And the new county sheriff, Ed Gonzales, has been vocal about overturning harsh immigration enforcement policies that have spurred the mass detention of undocumented immigrants.

Yet in pushing for progressive local candidates, TOP approached the election as a vehicle to advance a budding people’s movement, regardless of who won on November 8. “We always express to the members that the elected officials and ultimately campaigning politicians work for them,” Constance Luo, TOP’s voting drive coordinator, told me. “It’s never the other way around . . . so raise your voice, flip the paradigm of power, and make them work for you.”

Harris County’s traditional blue streak lies in its union-oriented working-class base. TOP’s labor ally, the Harris County Central Labor Council, made its usual get-out-the-vote drive on early-voting weekend with a team of beefy men in trucker caps, armed with tablets displaying addresses of fellow union members.

The mobilization started with a booming send-off in the cavernous union hall with interfaith consultant Reverend Ron Lister: “If you walk these streets, then keep in mind, that you are creating a new Houston! A new Texas, a new United States, a new world, a new spiritual consciousness. Let us pray . . . Protect each worker from pit-bull dogs, Doberman pinchers, Chihuahuas, and anything else . . . Empower us, strengthen us. This is our vote right now.”

But while Houston’s union base seemed reliably loyal, labor support for Clinton tumbled nationwide compared to Obama in 2012, with many defecting to Trump. TOP’s other voter drive that day centered on more promising terrain a few miles away, on a neat green patch known as Moody Park. There, a blaring Mariachi band serenaded the ditch-strafed working-class enclave, and families clustered around a sizzling taco grill astride a life-sized Trump piñata (pointedly stuffed with nothing but hot air) outside the polling site. The community gathering, organized by TOP in collaboration with a Latino-focused mobilization campaign named Tacos & Votes, aimed to make early-voting week a festive civic ritual in Houston.

Observing neighbors and activists celebrating the early vote, Beatrice, a seventy-seven-year-old homeowner whose Mexican-American family goes back generations in Texas, remarked, “This one is awful, this year. . . . It’s not really about politics. It looks like it’s about personality.” She had voted early, all Democrat as usual. Of the two leading candidates, she said, “I wish there were another choice.”

A retiree from a clerical job with an oil company, Beatrice empathized with the economic frustration roiling in the charged political atmosphere; she chafes at Houston’s rising cost of living and her thinly stretched fixed income. But the ascent of Trump’s “build the wall” demagoguery alarmed her, the daughter of a Second World War veteran. Immigration, she observed, had “never been an issue anywhere I’ve gone, because we’re all native Texans.”

“Where are we gonna end up? That man is weird in the head,” she said of Trump, but “so many of the things he says is what they want.”

|

|

|

Who exactly “they” are, though, was actually in play in Harris County and other battleground territories of the otherwise red state. Though Texas remains a Republican bastion, the “browning” of the southern electorate has been driving some cities leftward, as Latinos and other voters of color tend to favor Democrats, and are steadily turning swing states like Nevada and Colorado purple.

Texas is roughly 38 percent Latino, but according to recent election data, fewer than half were eligible to vote, compared to nearly 80 percent of the state’s white population. Of those eligible to vote in 2012, fewer than half actually cast a ballot. Still, while Texas ranks only twenty-third in the country in statewide Latino voter eligibility, this demographic constitutes over a quarter of eligible Texas voters. And since 2012, estimated Latino voter registrations rose by about 530,000, apparently spurred both by targeted voter mobilization efforts and a general growth in population.

Following several weeks of knocking on doors, distributing bilingual voting guides, and shuttling about 2,000 early voters to the polls, TOP’s data analysis showed Harris County’s Latino turnout during early-voting week, from October 24 through November 4 in 2016 was double what it had been in 2012. Some 155,000 registered voters TOP contacted across the county reported voting early.

Pre-election surveys indicated that immigration was the top issue driving Texas’s Latino voters. In the United States as a whole the overall Latino turnout was 13.1 million to 14.7 million, up from 11.2 million in 2012. An estimated 79 percent voted for Clinton—but her overall support was at lower rates than the turnout for Obama in 2012, and still not enough to turn key swing states.

TOP’s “ground game” is directed more toward strengthening local civic culture by organizing black and brown voters—historically the most underrepresented groups in local and state politics—than it is to winning elections. In Houston, San Antonio, and Dallas, the organization has run campaigns designed by its membership, including post-hurricane home rebuilding, legislation setting fair-wage standards for local firms, and cleaning up neighborhood pollution. TOP uses electoral organizing to amplify street-level organizing work in order to influence local officials.

TOP sees local officials as key to its broader program for criminal justice reform, which in turn helps alleviate social distress in their communities. After helping turn out a slim margin of victory for Houston’s democratic mayor last year, TOP hopes a more progressive law-enforcement approach will lead the city to redirect public funds away from jails and courts and into programs for community revitalization. TOP has pushed for the restoration of Sunnyside, a historically black community that has for years suffered chronic poverty and unsustainable housing costs. The community coalition behind the plan demands that public services and infrastructure be “provided equitably in low-income neighborhoods of color, at the same levels they are provided to privileged neighborhoods of whites.”

TOP’s vision for Sunnyside is the kind of place Tarsha Jackson, a middle-aged black woman with a tough smile, would have liked to raise her son. Jackson traced her reluctant politicization to the early 1990s, during the first Clinton administration. She first got entangled in a spate of traffic violations, she said, and then spent years cycling through the courts, trapped by the fines and fees that are routinely imposed on poor residents of color. By the time she emerged from the legal mire, Jackson, a former bank agent, recalled that her young son, a special-needs student, entered the criminal system himself. What his school deemed “misbehavior” ended up bouncing him from juvenile detention to adult prison. She considers her son, who is finally getting out of prison, as being “raised by the state.”

Years ago, Jackson noted, “When I was fighting for my son, I didn’t know the responsibility of the District Attorney and the County Judge.” As a survivor of the criminal justice system, she focuses on “educating the community [so] they start connecting [the elections to] the issue that I’m having in my neighborhood, and my schools are shutting down, and then we don’t have no sidewalks. . . . The reason I’m here is because I want to make sure that people know that they do have a voice.”

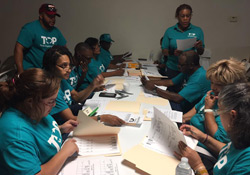

TOP’s voices rang out across Houston from its phone-banking headquarters on Halloween afternoon in 2016. Political director Tarah Taylor, dressed as a comic superhero, stood before tables of callers and a Trump piñata festooned with epithet-filled sticky notes and explained a controversial ballot referendum. The proposal was to redirect Houston school district funds, marked as “excess” property tax revenues, back into state coffers under a scheme to redistribute resources to poorer districts. Though it sounded like a fair funding measure, activists dismissed it as a rob-Peter-to-pay-Paul stopgap. Despite the district being deemed “property rich,” Houston schools have suffered with impoverished classrooms and deep budget cuts.

Callers should urge a “no” vote, Taylor said, to show that “the legislature has to figure out how to fund education, be it the rainy-day fund, taking money from border patrol, whatever they got to do. They need to put a priority on Texas children, and not try to . . . make homeowners pay for it.”

As they punched through their phone lists, the callers marked the poll rides they arranged by ringing miniature red cowbells. A few days later the proposition was defeated by over 60 percent.

Rosemary Escalante, a middle-aged sandy-haired retiree, was recruited to the bank from the other end of the line. A call from a TOP campaigner during a previous voter drive drew her curiosity and led to a visit to the office. Soon, she was attending meetings and joining protest rallies, inspired by TOP’s campaigns for criminal justice reform. It was a big change from her previous job processing warrants for the Houston police department.

“My total way of thinking [before] was that yes, I’m activating the warrant, but it wouldn’t be issued if he was a good boy, so he’s getting what he deserves,” Escalante said. “But I wasn’t seeing the entire picture. If you don’t have money, you’re treated differently.” As she’s become more involved with activism, she says, “I’m seeing it from the other side, and how some of the laws are so unfair to certain people.”

The law wasn’t just unfair to Miguel Fuentes, it downright ignored him. The Mexican-born Houstonian represented Texas’s newest and most precarious voting bloc on the Saturday of early-voting week at the Moody Park polling site. When he showed up to vote early, however, he discovered his name had been purged from the registration list. Fuentes, who said he has been a citizen since the early 1990s, was shocked when he was told his name had been scrubbed automatically during a routine screening of the registration rolls, just because he had not voted in the recent federal elections. (Controversy erupted in 2012 when reports emerged of a statewide purge of voter rolls under a seemingly arbitrary plan to cull supposedly erroneous records of “dead voters.”)

The disputed delisting of voters was one of a number of polling mishaps in the election. A few weeks before the election, a court order suspended Texas’s new voter-ID law, which civil rights groups argued were discriminatory to blacks and Latinos, and would potentially disenfranchise some 600,000 people statewide. But the first days of early voting were marred by reports of polling machine mishaps and widespread complaints from some high-Latino precincts about voter harassment and intimidation. Trump stoked these anxieties with baseless, fear-mongering allegations about “voter fraud” by undocumented immigrants.

With nationwide outreach efforts, civil rights activists went into overdrive, fearing that Latino voters could be deterred from voting in tight districts. Even as projected Latino turnout in southern states appeared to be surging, particularly in Georgia, North Carolina, and Florida, complaints of voter deterrence and logistical mishaps kept rolling in. A nationwide voter survey ahead of the election indicated roughly four in ten Latino voters facing obstacles, including being unable to locate their voting locations.

“That’s the way to suppress voting in the community. . . . My citizenship is for life, it’s not for every four years,” Fuentes said sternly as he called, seemingly in vain, a voter hotline outside the polling center. He eventually resigned himself to the possibility that his ballot had been legally stolen.

“The system’s kind of corrupt for me,” he said. “I don’t want to give up. But the thing is, you try to suppress us, it’s gonna make us bigger. . . . This is attacking our community.”

With an untold number of voters like Fuentes reportedly blocked or obstructed at the polls, Trump’s electoral win seems even more absurd. But for TOP, it mattered more that Fuentes remained politically defiant despite his disenfranchisement. Each individual voter they mobilized mattered more than any single ballot cast, for any candidate.

After the election, Luo said TOP’s major electoral achievement was to turn Harris County bluer than ever, up and down ballot, by sweeping local offices. In the wake of Trump’s victory, activists were readying their defenses on a familiar frontline, having battled anti-immigrant state and city legislators for years.

“Right now, more than ever, our members and the wider Harris County [and] Texas community in general realizes how important it is to stay united,” Luo said. “Because really, we’re not just fighting against one man. The target itself is never just one person, President Trump. It’s multiple targets. . . . Texans are ready for the fight.”

Omar Perez’s fight was never about elections, really; the clean-cut twenty-six-year-old Mexican immigrant and former teacher has temporary deportation reprieve under the Obama administration’s “Deferred Action” program for undocumented youth. On the campaign trail, Clinton had promised to renew the measure if elected; Trump has vowed to repeal the program and ramp up deportations while building his “wall” with Mexico.

As Election Day drew near, Perez’s fate hinged on the election even though—and, in fact, precisely because—he had no direct say in the race. But he could join TOP’s canvassing team to turn out his community’s vote instead.

On his poll-driving rounds on the only Sunday of the early-voting period, Perez recounted that he had been surprised to hear many local voters denounce Trump not so much because of his racial animus, but because they resented his wealth and arrogance. Yes, racism was a factor, but “subconsciously, they know that it’s a class issue, in a way.”

Trump sought to “use fear and ignorance, so these poor white people can blame other poor minorities for their problems, when in reality it’s not the minorities that are the problem,” he continued. “It’s the ones on top—the wealthiest of the wealthiest . . . What should matter is that we’re not treated equally. . . . We need to unify.”

His last pick-up of the day was the rumpled cottage of an eighty-six-year-old Mexican-American man, who ambled with a cane down the poll line at his local community center. A member of Houston’s New Deal–era working class, the former factory worker said he had lived in his neighborhood for about half a century, each year stubbornly voting Democrat. That same political sensibility was finally turning Harris County blue, up and down the ticket, with the help of younger residents like Perez, who are committed to staying put, with or without a vote.

“I feel more involved than any other citizen. . . . The Latino vote, they don’t know how much power they can have,” he said. “It’s like a sleeping giant, and we’re waking that giant up.”

Michelle Chen is a contributing editor to Dissent and co-host of its Belabored podcast.