A New Hope for Mexico?

A New Hope for Mexico?

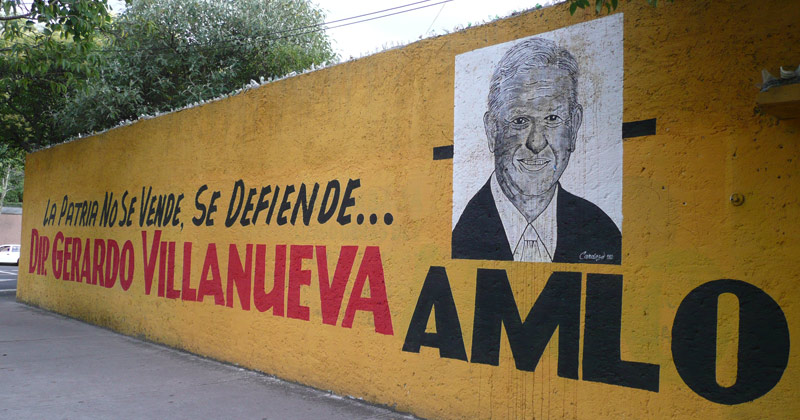

Andrés Manuel López Obrador is hardly the demagogue of his critics’ imaginations. The more relevant question is: if he becomes Mexico’s next president, will he actually bring the changes the country needs?

These diverse and even opposing reactions speak to the anxieties of their authors—as well as to the ambiguities that AMLO himself has cultivated over his many years in politics. Still, these comparisons to foreign leaders are misleading and frequently superficial, focusing excessively on personality while neglecting the political conditions that have both made AMLO a viable candidate and will shape his presidency if he wins. As of late February, AMLO looks like the clear frontrunner, and the likely next president of Mexico. But the coalition he is assembling will probably not constitute a solid majority, and the political situation he is likely to enter into may make the transformative changes that people either expect or fear from him difficult to carry out.

Mexico’s electoral field in 2018 is complex and fragmented. It bears the strains and disappointments of the country’s relatively recent democratization. For most of the twentieth century, Mexico was governed by the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) and its ideologically flexible form of machine politics. Presidential re-election was banned, so every six years the president chose his successor from the same party. Leadership changed regularly, while the party used electoral mobilization, patronage relationships, and sometimes fraud to retain control of Congress, governorships, local legislatures, mayoral offices, as well as the unions, government bureaucracies, and most of the press.

Opposition parties were allowed to organize but not to rule; some even got subsidies from the PRI and became official “satellite” parties. The most serious opposition party was the Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), a center-right party founded in 1939, which appealed to conservative Catholics and middle-class professionals, and became especially strong in the cities and in the more industrial northern states. But before the 1990s, the PAN—and any other genuine opposition—was excluded from national power.

Ideologically, the PRI contained multiple currents. Its left wing looked back to the “national-revolutionary” tradition of Lázaro Cárdenas, Mexico’s president from 1934–1940. Cárdenas nationalized Mexico’s oil, redistributed land, implemented secular, socialist education, and welcomed radical exiles from around the world, including thousands of republicans fleeing Franco at the end of the Spanish Civil War. He also consolidated much of the PRI’s corporatist structure that lasted for decades to come, with workers, peasants, and professionals represented (and managed) from within the party. Cárdenas understood this form of corporatism to be democratic, since it included ordinary people and gave them a place in the party, but it also preserved single-party rule. Even during periods of conservative dominance within the PRI, the “national-revolutionary” wing remained important, running left-wing candidates in local or regional elections and containing political opposition within the bounds of the PRI.

For a time, AMLO was just such a figure. Born in 1953 in a small town in the tropical southern state of Tabasco, AMLO came of age politically in the 1960s and ’70s. He joined the PRI in the mid-70s, supporting the 1976 senatorial campaign of his friend, the Catholic socialist poet Carlos Pellicer. He identifies strongly with Lázaro Cárdenas and with Benito Juárez, the nineteenth-century liberal president of indigenous heritage whom AMLO understands to represent a responsible, public-spirited, nationalistic, and popular approach to government. Among figures from his own time, he describes Salvador Allende, the elected socialist president of Chile who was overthrown in 1973, as the non-Mexican he most admires: “a humanist, a good man, a victim of despicable bastards.”

In 1982, AMLO was put in charge of a progressive PRI candidate’s gubernatorial campaign, promising “democracy and social justice” and working to renew local Cardenista-style participatory organizations to take control away from party bosses. His candidate won, but the party pushed back. AMLO resigned from the government. “We had tried to democratize the PRI with a progressive governor and it could not be done,” he wrote. “From that moment on, I reached the conclusion that the PRI was beyond hope.” Only through competing opposition parties could Mexico be democratized.

That same year, an unprecedented debt crisis led to devaluation of the peso and massive capital flight, pushing the government to nationalize banks and impose currency controls. This brought about a break between the PRI and the hitherto depoliticized business community, which started to gravitate toward the center-right opposition, the PAN. Moreover, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund mandated structural adjustment policies to deal with the crisis, and the reforms undermined the PRI’s relationships with the unions and peasant organizations it counted on for popular support. The elaborate structure supporting the PRI’s hegemony became unstable.

With the benefit of hindsight, other signs of Mexico’s democratization can be seen throughout the 1980s. The negligent official response to a massive 1985 earthquake in Mexico City robbed the regime of legitimacy, and the civic mobilization that followed began transforming the city into a hub of left-wing opposition. In 1986 the PRI carried out what it described as a “patriotic fraud” to keep control of the governorship of the northern state of Chihuahua, prompting opposition rivals to form a left-right coalition in an (unsuccessful) attempt to defend electoral integrity. In 1988, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, son of Lázaro Cárdenas, mounted a serious challenge to the PRI from the left. The PRI held the presidency in an election marked by irregularities; many believe Cárdenas was the legitimate winner. The next year the coalition supporting his candidacy formed the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD), which united various strands of the Mexican left.

AMLO immediately joined the PRD and became its leader in his home state of Tabasco, and ran for governor as the PRD candidate in 1994 (as he had in 1988, supported by a coalition of small leftist parties). Since the PRI used its corporatist organizations to influence civil society, assembling a political counterweight meant creating parallel media outlets, parallel peasant organizations, and parallel benefits for those who would participate. AMLO couldn’t win the election—not least because of fraud—but he was building a party and a reputation. After a demonstration, he appeared bloodied on the cover of Proceso, Mexico’s most important left-wing newsmagazine. In 1992 and 1995 he led 600-mile-long marches to Mexico City to protest against electoral fraud in Tabasco. In 1996 AMLO became the national leader of the PRD, a position he maintained until 1999.

His term was successful. Between 1990 and 1996, successive waves of electoral reform engendered an autonomous electoral authority, the Instituto Federal Electoral, that made elections fairer and freer. As a result, in 1997, two important turnovers occurred. For the first time, the PRI lost a congressional majority; the PRD doubled its representation in the Senate, and nearly did the same in the Chamber of Deputies. In addition, the position of Mexico City mayor became elected, rather than presidentially appointed, and it was won by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas.

In 2000, the PRI finally lost the presidency, not to the left but to the PAN candidate: center-right former businessman Vicente Fox, who ran on a minimal conservative program of defeating the PRI while retaining neoliberal economic orthodoxy. The PRI still held many regional, legislative, and bureaucratic centers of power, and Fox’s government was perceived as aimless, improvised, and erratic, partly because resistance from entrenched interests prevented change and partly because Fox himself privileged stability over transformation. As political scientist Gibrán Ramírez told us in an interview, democratization was limited to the imposition of a new set of political rules; it was a fundamentally procedural achievement, bearing “a deficit in terms of the egalitarian promise of democracy.”

AMLO’s supporters see him as capable of restoring that forgotten promise. Although hailing from Tabasco, hundreds of miles away, AMLO served as mayor of Mexico City from 2000 to 2005, and his term as mayor brought him considerable renown. He promised honest government and sought to embody it, living in a tiny house in a middle-class neighborhood and driving a basic Nissan Tsuru (the most common car in Mexico at the time, especially favored among cab drivers). He delivered early-morning news conferences every day, worked up to eighteen hours, and remained disciplined and focused. His approval ratings sometimes soared above 80 percent.

The beginning of the “pink tide” in Latin America is often dated to 1999, when Hugo Chávez was elected in Venezuela, and Mexico is said to have missed out. But Mexico City is different: It has been governed by the PRD continuously since 1997. It has the second-largest population of any city in the Americas, making it an important base on which to test out new policies. And its mayor is usually Mexico’s second-most-influential politician, well positioned for national office. These points were not lost on AMLO, who, while mayor, significantly expanded local social programs. He gave out cards with monthly cash allotments to senior citizens, single mothers, the unemployed, and the disabled; built social housing and schools, including a new public university; and reduced salaries for city officials. He was a successful mayor, though hardly a radical one. AMLO partnered with Mexico’s richest man, Carlos Slim, to redevelop the city’s historic center. His government inaugurated a bus rapid transit service used more by the middle class than the poor, and its major infrastructural project was an elevated highway that benefited car owners.

Furthermore, AMLO has never been particularly socially progressive. He talks with a language of moral renewal and social reconciliation that has profoundly conservative undertones. It was his successor, Marcelo Ebrard, who decriminalized abortion and legalized same-sex marriage in Mexico City (while it remained illegal in the rest of the country). In 2001, after a lynch mob killed a burglar trying to steal from a church in a rural corner of Mexico City, AMLO defended the incident by arguing that “it is better not to mess with popular traditions, with the people’s faith.”

The final years of his term were marked by scandal. In 2004, videos displayed on national television showed close associates of AMLO’s gambling in Las Vegas and receiving thousands of dollars in cash bribes. He blamed the attacks on his colleagues, as he usually does, on a “mafia of power”—a cabalistic power elite working to protect its privileges. The “mafia” charge does capture the oligarchic qualities of Mexico’s political system, and in this case was partly true: it was later revealed that the videos were made public after one of the shady businessmen involved was paid off by AMLO’s political opponents. But ascribing everything to the “mafia” can also serve to deflect attention from problems in AMLO’s own camp.

In 2004, Vicente Fox’s government revived an old legal controversy regarding a plot of land in an upscale neighborhood, which AMLO’s predecessor as mayor had expropriated in order to build an entrance to a private hospital. After the owner of the plot filed a suit, a judge ordered construction to stop until the matter was definitively settled. AMLO broadly obeyed the judge’s order but the Federal Department of Justice asked Congress to impeach him. The PRI and the PAN voted to remove him from office. Polls showed a majority of Mexicans disagreed with the impeachment and saw it as a politically motivated move to block AMLO from appearing on the 2006 presidential ticket. Massive protests ensued, the most important of which drew almost a million people to the Zócalo, Mexico City’s central plaza. In the end, Fox fired the head of the Department of Justice and appointed a new one who backpedaled. AMLO had been removed from his post as Mexico City mayor but was now free to run for president.

He soon became the leading candidate. AMLO’s approval ratings as Mexico City mayor had been consistently high, and in January 2006, polls gave him a 9 percent lead over his chief rival, Felipe Calderón of the PAN. During the campaign, he made costly mistakes—telling the president “¡Cállate, chachalaca!” (“Shut up, noisy bird!”), not attending one of the debates, and openly dismissing polls that showed his advantage was shrinking. The PAN and its allies attacked him as a dangerous figure who would destabilize the economy and behave like Hugo Chávez.

On election night, results were too close to call. Official numbers revealed that AMLO lost by a quarter of a million votes, about half a percentage point. He claimed to be a victim of fraud, and filed a poorly crafted legal challenge that the Federal Electoral Tribunal easily dismissed. But his supporters poured into the streets and he launched a massive, two-month long plantón (sit-in) on Mexico City’s most emblematic avenue, Reforma. In the end, he set up a kind of shadow cabinet with no real power and declared himself the “legitimate president of Mexico.” His public image collapsed.

After the disputed electoral results of 2006, Felipe Calderón’s presidency was marked by two trends. One was the dramatic militarization and escalation of the conflict with drug cartels and organized crime. The death toll during his term (about 121,000 homicides) was about eighteen times the number of Americans who died in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars combined (about 6,800 deaths). This “war” made the issues of drug trafficking, impunity, and violence the most important factor governing life in many parts of the country. The other trend was a much more silent but no less painful reversal: since 1996, poverty had been constantly declining for a decade, but during Calderón’s administration it started to rise again. For many Mexicans, the notion that democracy could open a way out of poverty proved itself to be an illusion.

AMLO decided to run for president again in 2012, sidelining his progressive successor as Mexico City’s mayor, Marcelo Ebrard, in the process. He rose steadily in the polls, from third place to a final tally of around 32 percent of the vote. But he didn’t overtake Enrique Peña Nieto, the PRI’s candidate, a TV-handsome doofus married to a telenovela actress. A former governor of the Estado de México (which partially surrounds Mexico City) Peña Nieto had been groomed for the position for years, hoping to recover the PRI’s traditional position and promising, above all, to get things done. An informal saying summarized (half jokingly, half seriously) the reasoning behind his victory: “que se vayan los pendejos y regresen los corruptos” (let the incompetents go and the corrupt return). It was a rejection of the PAN’s government, but also a rejection of the intransigent opposition that AMLO epitomized after his loss in 2006.

Peña Nieto’s victory—and AMLO’s loss—sparked a crisis within the left. The PRD used to represent a truly historic achievement: a united party transcending decades of left fragmentation. Still, it had always been a messy coalition, with characteristics of both a social movement and a political party. After this second presidential defeat, AMLO decided he would leave the PRD to start what became, in 2014, a new party: MORENA (an acronym for Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional). It was a vehicle for AMLO to enhance his personal leadership and to free himself from the political restrictions and factional struggles that consumed the PRD. But it meant that there were two parties positioned on the left, competing for some of the same votes.

As soon as Peña Nieto got to power he announced an ambitious agenda to “move Mexico,” especially beyond the sluggish 2.2 percent economic growth it had averaged in the preceding decade. The agenda included neoliberal reforms of the energy, financial, and telecommunications sectors, most of which were carried out under the umbrella of the “Pacto por México”—a legislative coalition including the PRI, the PAN, and the PRD. AMLO opposed all of the reforms, but didn’t mobilize his base to stop them.

If the results proved underwhelming at first, they soon turned disastrous. The Pacto por México of Peña Nieto’s first two years in office has given way to crime, economic disappointment, and corruption scandals. The violence has been stunning: from the rise of vigilante groups, extrajudicial killings, and the unsolved and widely publicized disappearance of forty-three teachers-in-training from Ayotzinapa. The year 2017 has set a record for homicides, and economic growth has remained weak. Peña Nieto’s government may be one of the most corrupt in the country’s history. Most notoriously, the president himself was involved in a case where he used a government contractor to build his wife a mansion in Mexico City’s most exclusive residential neighborhood. But there has been a seemingly unending series of scandals involving cabinet members, party leaders, governors, legislators, mayors, all implicated in both small and large schemes of graft, money laundering, and resource diversion.

AMLO has worked hard to maintain an image of pure, moral opposition to this kind of dishonest government—in spite of the corruption scandals roiling some of his associates. He insists over and over again, paraphrasing a verse from the Mexican poet Salvador Díaz Mirón, that “there are feathers that cross the swamp and do not get dirty. . . . My plumage is one of those!” In one ad, he criticized Peña Nieto’s new presidential airplane by saying that “not even Obama has one” so luxurious and that in 2018 “we will sell it.” The phrase was easy to turn into a meme and soon spawned countless variations and jokes on the internet. It was light mockery, but helped represent AMLO’s fundamental message that “there cannot be a rich government and a poor people.”

All of the established major parties, then, enter the 2018 election with some level of discredit. After its defeat in 2012, the PAN underwent a period of instability, change, and renovation of leadership that left it in many ways unrecognizable. The PRD, meanwhile, is staring down its increasingly minority status. With the departure of many of its members, operatives, and activists to MORENA, all that remains is a moderate wing without a large social base. The startling response from both PRD and PAN has been to join forces and co-nominate the PAN’s national leader: a thirty-eight-year-old rising star named Ricardo Anaya, with a PhD in Political Science from Mexico’s National University and little political experience. Above all, Anaya is known for his remarkable ability to defeat his rivals, both within and beyond the PAN. One of those rivals, Margarita Zavala, wife of former President Calderón and relatively popular among Panista voters, left the party and will try to run as an independent candidate—a move that in all likelihood will hurt Anaya. As a candidate of a center-left/center-right alliance, Anaya will be forced to be a centrist who, somehow, is also bold and audacious. He will be the candidate of a coalition of politically correct moderates, who are both angry with the PRI and scared of AMLO.

Given Peña Nieto’s unpopularity, the PRI had to try a different kind of candidate, and nominated orthodox technocrat José Antonio Meade, a lawyer and economist with a PhD from Yale who has worked in both PAN and PRI administrations. But as of late February, with pre-campaigns coming to an end, it seems that some of the PRI’s core voters are rejecting Meade, who prides himself on being a “citizen-candidate”—that is, not a member of the party—and are considering moving toward AMLO.

The difficult situation facing all of the other parties leaves AMLO as the clear frontrunner. Whether people love or fear him, he has a strong national standing. His reputation for personal austerity makes a good contrast with the things that voters dislike about the current government. He has dedicated and enthusiastic followers, who have been organizing for many years. MORENA is unified behind him in a way that the other parties, or alliances, cannot be with their candidates. A solid third of voters favored him previously—he officially won 35.3 percent of the vote in 2006, and 31.6 percent in 2012. Mid-February polling showed him with similar or even higher levels of support during the 2018 pre-campaign period, eight to ten points ahead of Anaya, his closest rival, in a field of five.

As a relatively new party, however, MORENA lacks many of the advantages that the other parties have. In spite of gaining a lot of ground against the PRD, MORENA still has not won any governorship; as of the 2015 national elections, it is the fourth-largest party in terms of votes (8 percent) and the fifth-largest in terms of seats in the Chamber of Deputies, akin to the U.S. House (35 out of 500); and it needs to make significant inroads in the Central and Northern regions of the country, where the left has never been strong.

Moving beyond his base to make a path to victory remains the challenge for AMLO. He is trying to forge a broad coalition. Apparently recognizing the need to win over conservatives, AMLO is running both under MORENA’s banner and that of the Partido Encuentro Social (PES), a far-right evangelical party that might add one or two percentage points to his tally. The PES’s agenda is at odds with AMLO’s leftist credentials—although not necessarily with his personal beliefs nor those of some of his followers. In two years of canvassing experience in Mexico City, Sebastián Ramírez, an organizer for MORENA, told us he has only once been told “I used to vote for [AMLO], but now you are against abortion.” Far more common is to find someone who will take out their Bible and show him the photo of AMLO they have tucked inside, saying that they are praying for him. This sort of political discovery has led to a reckoning in the movement, what Ramírez describes as “a big learning process within lopezobradorismo.”

“Yes,” he told us, “we are guilty of wanting to win elections. And for that, we have chosen not to have a proper ideology but certain principles, certain expectations around which we try to bring together large sectors of society.” Where some see opportunism, Ramírez sees “a way of democratizing the left, of getting rid of ideological dogmatism.” He continues: “Right now we are in an exceptional situation—this is our best opportunity to win the presidency. And this has to force us to accept a lot of things, to update ourselves and align our strategy to reach all of our potential constituencies.”

In spite of the “unnatural” alliance between MORENA and PES, it is likely that most socially progressive voters, most of all from Mexico City, will still vote for AMLO. They have nowhere else to go, since all other candidates are socially conservative as well. More fundamentally, MORENA is still the most credible opposition to what lopezobradoristas call the PRIAN (combining the PRI and the PAN) and he has been fulminating against it for eighteen years. Since Mexico became a democracy, both the PAN and the PRI have had a chance at the presidency. The most likely option for voters who want change—even if they disagree with particular aspects of his style or his agenda—is AMLO.

AMLO’s greatest strengths are his persistence and popular appeal. He has correctly identified the most pressing ills that have undermined Mexico for a long time: rampant corruption, extreme poverty, regulatory capture, and wasteful government spending. Yet, even if his diagnoses hit the mark, his solutions lack institutional perspective and policy specifics. His movement is afflicted by a great-man theory of history in which a change in leadership will, by itself, turn things around. In this regard, sometimes it seems that AMLO’s most important proposal is AMLO himself.

The first draft of MORENA’s program, which was released last November, does very little to ease such concerns. Even though social policy against poverty was AMLO’s strong suit as Mexico City mayor, MORENA’s platform is an embarrassingly uneven 415-page document devoid of any clear sense of priorities, with some interesting proposals about wages, development, and public health services; some flagrant contradictions in regards to internal security, justice, and energy policies; and barely a mention of women’s rights, discrimination against minorities, or a social safety net. Asked why the platform was in such disarray, Alfonso Romo, a former pro-Fox businessman and agro-industrialist from the northern city of Monterrey who has become very close to AMLO, answered that even though some of the ideas did not make sense, they were incorporated because the drafters wanted to make everybody feel included.

In the same spirit, AMLO has opened his movement to a motley crew: business leaders, B-list celebrities, a soccer star turned politician, former Priístas, Panistas, and many Perredistas, some with highly questionable reputations. In mid-December, he presented a kind of preliminary cabinet. It had a bit of everything: a former Supreme Court Justice well known for her progressive politics; a couple of private-sector darlings; a Harvard-educated economic historian specializing in industrial policy; two children of old-time lopezobradorista loyalists; and a distinguished economics professor who had a run as Mexico City’s finance minister during the first half of AMLO’s tenure as mayor. Some of his cabinet members have publicly defended positions that are at odds with AMLO’s. But somehow this doesn’t seem to matter. “Everybody deserves a second chance,” he says proudly.

All this amounts to a very different situation than those who reach for analogies with other political figures—from Mexico or abroad, past or present—have reckoned with. However much a MORENA government might want to resemble the old left-wing nationalist government of Lázaro Cárdenas, for example, it would be difficult to replicate this model in a setting that is not post-revolutionary, in such a fragmented political landscape, or with an economy as complex and integrated as contemporary Mexico’s. Even if AMLO performs well in the election, it seems unlikely that he will have a strong congressional majority, or that he will have enough allies at the state and local levels to build something resembling the mythical Cardenista Leviathan. The messy compromises of coalition politics will be inevitable. By the same token, those who fear a Mexican Hugo Chávez should recognize that AMLO’s term as mayor was hardly radical, that he is neither an outsider nor an ideologue, and that he comes from the world of civilian politics rather than from the military. The strength of his movement and the extent of his popular support pale in comparison to those of Chavismo, and the fragility of Mexican public finances, plus the low price of oil, render such a possibility even more remote.

If AMLO’s detractors are unlikely to see their worst fears realized, his enthusiasts are almost certain to be unsatisfied as well. If AMLO is no Hugo Chávez, he will find it equally difficult to emulate Brazil’s Lula, who enjoyed high commodity prices and a deep well of popular support during his term in office. Even if he performs well, he will still find himself facing a multitude of powerful, frightened forces committed to boycotting his administration from day one. At the same time, AMLO’s socially progressive supporters have already been given several signals that their rights and diversity agenda is not a priority. Economic progressives who care about inequality will probably find that the Mexican state’s current capacity to implement and sustain significant redistributive efforts is limited, and that improving it will require herculean and improbable reforms. AMLO has promised not to raise taxes, instead seeking savings by fighting corruption. As important as that is, it can’t possibly be enough—particularly without a clear policy course on how to produce actual results in such a fight. Progressives will also have to grapple with the fact that in assembling his 2018 coalition, AMLO is tending more toward conciliatory rather than transformative goals.

AMLO’s critics portray him as a danger to Mexican democracy, and it’s true that his personal leadership style might test the strength of its institutions. But so would the election of any other candidate. AMLO’s election would also be a testament of democratic normalcy: he is the strongest opposition candidate confronting a deeply unpopular administration. The real issue, perhaps, is that Mexico’s greatest problems—massive inequality along with devastating crime and violence—cannot be fully resolved by its political system. In that, too, Mexico is hardly alone. It is merely one face of the great problem of our time, as oligarchic pressures crowd out democratic ones. MORENA’s slogan is “Mexico’s hope,” and Mexicans have sorely earned it. But what comes after hope?

Carlos Bravo Regidor is associate professor and coordinator of the journalism program at the Center for Economic Research and Teaching (CIDE) in Mexico City.

Patrick Iber is assistant professor of history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He is the author of Neither Peace nor Freedom: The Cultural Cold War in Latin America (Harvard University Press, 2015) and a member of the Dissent editorial board.

[contentblock id=spring-2018-teaser]