Hunger at the End of the Supply Chain

Hunger at the End of the Supply Chain

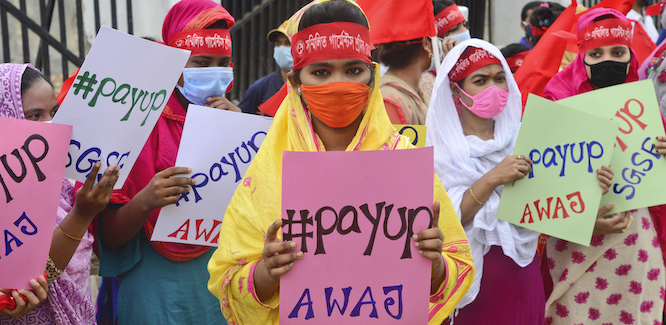

The workers who sew clothes for global apparel giants are facing widespread hunger and destitution during the pandemic—even as many of these corporations continue to turn a profit.

A Bangladeshi woman loses her factory job in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before, she was able to afford the occasional purchase of meat, fish, and fruit for her family. This is no longer the case. “Egg is a luxurious food for us now,” she says.

In Indonesia, a garment worker whose monthly income has dropped by 20 percent since the beginning of the pandemic begins her days with a devastating calculus: should she eat, or go hungry to avoid accumulating more debt?

A garment worker in Myanmar goes to the market and purchases food that would have lasted her family a week before the pandemic. But because she and her family are rationing their food intake, the same amount of food has to last two weeks instead of one.

Far from a handful of rare episodes, these stories illustrate an alarming trend in the global apparel supply chain: the people who sew clothes for major apparel giants around the globe are facing widespread hunger and destitution as a result of falling income and job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic. In September 2020, we launched a survey to understand the impact of changes to garment workers’ employment status and income levels on food security. We interviewed 396 workers in nine garment-exporting countries. Our survey respondents included workers who were temporarily suspended or permanently fired, as well as those still employed. They reported sewing clothes for well-known brands and retailers, such as Adidas, H&M, Inditex (the parent company of Zara), Nike, Target, and Walmart. In late 2020, we published our findings in a report called “Hunger in the Apparel Supply Chain,” which documented job loss, declining incomes, and food insecurity among the world’s garment workforce.

Our survey found that hunger is a growing and acute problem not only for workers who have lost their jobs, but also for those who are still working. Of the workers in our survey, 88 percent stated that diminished income—whether the result of losing their jobs without being paid a legally mandated severance, being sent home without pay from a factory that was shutting down temporarily, or losing income despite still being employed—had forced a reduction in the amount of food consumed per day by members of their households. And 77 percent told us that they or a member of their household have gone hungry since the beginning of the pandemic, while 80 percent of workers with dependent children said they are forced to skip meals or reduce the amount or quality of food they eat in order to feed their children. Three quarters of the survey respondents have borrowed money or accumulated debt in order to buy food since the onset of the pandemic. And 80 percent told us that they anticipate continuing to reduce the amount of food they eat or purchase for their family if the situation does not improve. Garment workers experienced widespread and growing hunger despite the fact that half of them had received some form of public assistance.

This growing trend of food insecurity is the result of the chronically low wages and precarity in brands’ supply chains that predated the pandemic, compounded by apparel companies’ irresponsible practices in response to the crisis.

In March 2020, retail stores shuttered their doors due to the spread of COVID-19, which led to a sharp and enduring decline in consumer demand for clothes. Rising unemployment and inequality wrought by the COVID-19 economic recession also led to a decrease in consumer spending on apparel. Faced with looming sales losses, the immediate response of many apparel companies was to shift the economic pain down the supply chain by abruptly canceling orders to supplier factories. In many cases, they did so retroactively and refused to pay for orders that factories were already manufacturing or had completed. Brands cited dubious force majeure clauses to skirt their contractual obligation to pay their supplier factories. Because supplier factories operate on razor-thin margins, factory owners responded to the economic shock by suspending or dismissing workers en masse, and slashing the hours and wages of millions of others. Supplier factories around the world reportedly lost over $16 billion in revenues between April and June 2020 alone, but garment workers were left to bear the cost of the crisis.

Since March 2020, pressure from trade unions, labor rights advocates, and consumers has led some brands and retailers to reverse course and pay for their bills. But this success has been partial; much remains unpaid. Making matters worse, a number of apparel brands placing orders for autumn and winter exploited their suppliers’ desperation for new orders and demanded lower prices and slower payment schedules, thus subjecting their suppliers to additional financial stress, which has translated to downward pressure on wages and accelerated job losses.

Apparel companies are not solely responsible for the plight of the world’s garment workforce in the era of COVID-19. This unprecedented public health crisis had colossal economic repercussions that no one was prepared for. But apparel companies are responsible for the uneven distribution of economic pain and the longer-standing inequities in global supply chains, which left workers exceedingly vulnerable to any economic shock.

For decades, apparel giants have championed a business model that relies on deep power and wealth asymmetries between brands and their suppliers. Apparel brands and retailers were able to outsource much of their economic losses during the pandemic down the supply chain because these chains are regulated in ways that allow brands to limit their obligations to suppliers. Brands dictate how profits are distributed along the supply chain, squeezing suppliers while claiming a disproportionate share of the gains.

Garment workers are left with the smallest piece of the pie. Chronically low wages in garment factories may be the most obvious manifestation of this dynamic, but it fosters a climate that is ripe for other forms of labor abuses as well. By continually lowering prices and demanding shorter turnaround times for orders, brands and retailers make it increasingly difficult for factory owners to adhere to labor laws and standards. Sourcing practices give suppliers a financial incentive to cut corners by withholding wages, failing to pay overtime, depriving workers of personal protective equipment, refusing to pay severance, and cracking down on workers who attempt to organize.

We cannot disentangle the income shocks, layoffs, and hunger garment workers are currently facing from the deep-seated injustice baked into the global supply chain. The workers we surveyed entered the COVID-19 crisis with no margin of economic security; their wages were so low that most of them weren’t able to accumulate any savings. Moreover, most apparel-exporting countries lack social protections such as unemployment insurance for workers who lose their jobs or have their hours cut. The protections that do exist are poorly enforced, as is the case with mandatory severance pay. Among the workers we interviewed who had permanently lost their jobs (roughly one fourth of the total number of workers in our study), 70 percent had not received their full legally mandated severance pay; 40 percent of them received none at all.

Workers have few options besides resorting to debt when they face sudden losses of income. In fact, chronic indebtedness was commonplace for garment workers even before the pandemic. Many workers now face high levels of interest with little prospect of earning enough to repay loans, a worrying dynamic in light of the well-documented links between debt, high-interest rates, and vulnerability to severe forms of labor exploitation.

Even during the pandemic, apparel giants have continued to turn a profit. Many have benefitted from government corporate aid packages. In the United States, major brands like Nike and PVH (the parent company of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger) accessed government loans through the 2020 CARES Act. And in Europe, companies including H&M, C&A, and Adidas received government support for employee wages. Mass market retailers like Amazon, Target, and Walmart have seen their sales soar during the pandemic. Other apparel companies, like Bestseller, C&A, and Zara, are owned by the planet’s most prominent multibillionaires.

Apparel companies urgently need to step up to ensure that garment workers’ income is sustained throughout this crisis, as unions and labor advocates around the world are calling on them to do. They need to pay suppliers in full for any orders they placed prior to the pandemic and immediately cease irresponsible sourcing practices that take advantage of supplier factories’ increasing desperation. Beyond these urgent, short-term demands, systemic change to address the gaping and increasing power and wealth inequalities within supply chains is long overdue.

The past few decades have seen a sharp and persistent rise in corporate-led initiatives to signal apparel brands’ dedication to improving the conditions of the workers that sew their clothes. These corporate social responsibility (CSR) projects assure us that there is no conflict between the goals of maximizing profit and social uplift for workers. But the CSR initiatives have failed to deliver concrete gains for global garment workers; they are designed to keep the current power dynamics within supply chains intact. Any corporate initiative purporting to protect garment workers is only as effective as its ability and willingness to disrupt power relations within supply chains and provide suppliers with sufficient income to cover the costs of legal and voluntary labor standards.

Crucially, apparel brands and retailers must recognize workers’ right to organize and bargain collectively. Drawing from the success of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh—a worker-driven, legally binding agreement between workers, factory managers, and apparel companies that have led to a safer and healthier garment and textile industry in Bangladesh—workers, trade unions, and their allies across the globe are demanding that brands and retailers make an enforceable commitment to pay a price premium on apparel orders to establish a global severance guarantee fund. This fund will not only ensure that workers who have been laid off receive legally mandated severance payments but provide garment-exporting countries with the financial support to broaden social protections at a national level, thus mitigating the risk of destitution for garment workers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

The Worker Rights Consortium and Clean Clothes Campaign estimate that it would cost brands and retailers less than 10 cents per T-shirt to enable garment workers to survive the pandemic and strengthen unemployment protection in the future. The apparel industry is more than financially capable of ensuring that the workers who sew the products that generate their profits are not left to starve.

Penelope Kyritsis is the Director of Strategic Research at the Worker Rights Consortium, an independent labor rights monitoring organization for the global garment industry.

Genevieve LeBaron is Professor of Politics at the University of Sheffield with a focus on labor and employment in the global economy. She is the author of Combatting Modern Slavery: Why Labour Governance is Failing and What We Can Do About It.