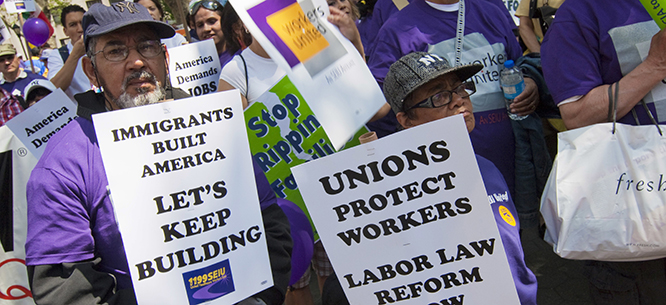

How Unions Can Protect Immigrants

How Unions Can Protect Immigrants

An interview with Faye Guenther, president of UFCW Local 3000.

In February, the labor reporter Luis Feliz Leon published an essay on the n+1 website on unions’ varying responses to Trump. We were intrigued by his mention of a members’ meeting organized by Faye Guenther, president of United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 3000, to discuss immigration and how the union could prepare for the new administration’s deportation plans. We spoke to Faye on February 28 about how she confronts divisions within her membership, and how unions can protect their immigrant members. Since then several union members have been detained—including former UAW member Mahmoud Khalil, Lewelyn Dixon and Rümeysa Öztürk of SEIU, and Alfredo Juárez of Familias Unidas por la Justicia—which only underscores the importance of this discussion.

Patrick Iber: You’re in daily contact with people whose experiences are shaped by changes in the immigration regime, whether they’re immigrants or not. Luis Feliz Leon reported that you had a meeting about immigration with United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) members. What did you hear from workers?

Faye Guenther: We’ve been doing scenario planning since April of last year, when we thought Donald Trump was going to win. We focused on the most likely threat, which was deportations.

We’ve been talking with our members for a long time about why unity has to be maintained when we’re protecting everybody at work. And we’ve been doing a ton of know your rights work: “Employers do not have to let ICE agents in without a warrant; here’s how to check a warrant.” And we were trying to negotiate that training into all of our contracts prior to Trump taking office. Because people have more rights than they think.

Employers have rights also. Employers do not have to scare the shit out of workers. They do not have to tell people that they could be fired. They don’t have to do anything. And employers do not want to lose their workforce. Kids do not want to lose their family members. I’ve seen kids who haven’t been picked up from day care. You need to have a plan for the worst-case scenario.

Iber: How has the membership responded?

Guenther: We’ve been talking and trying to build unity and solidarity between workers for a long time. For example, we took a strong stance on wearing masks and being vaccinated; if coworkers felt safer with people wearing masks, people needed to wear masks. That’s our duty to each other. There are some folks who don’t agree. But we work hard to build consensus, and if we can’t build consensus, we vote using majority rule.

Iber: There are big debates about whether a more homogeneous working class is easier to organize. And it seems to me that whatever debate they’re having about this in Denmark doesn’t apply to the United States. Our working class is diverse, and it always will be. Even if the Trump administration creates a terrible environment for recent immigrants, that’s not going to change. What message do you have to union leaders who might not be taking the same approach that you’re taking?

Guenther: Right now, there’s so much isolation in our society that the only place you’re interacting with people is at work. The workplace is where people care about each other, talk to each other, and of course disagree with each other. I think it’s a bunch of bullshit that people can’t, or think that they can’t, build unity among workers. Workers already care about each other. That’s just the natural way humans behave. White workers will stand with a worker who they know and who is going to get picked up by ICE and ripped away from their family. I’ve watched people stand together.

UFCW has the youngest membership of any union in the country. It’s majority women, because we work in grocery stores and healthcare facilities. And a big chunk of our workforce is people of color. When you have a predominantly white male workforce, then maybe you’re not getting exposed to the true stories of other people’s lives, and it might be harder to understand what somebody else is going through. But I think workplaces that are integrated, where you meet people from all walks of life, are super vibrant and a place where learning happens. I represent workers all across Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, and I’ve found rural and urban workers face the same things: the housing crisis, low wages, and shitty bosses.

Natasha Lewis: When there is disagreement, how does that process work? What questions are you asking?

Guenther: I’m a certified mediator, which I think has been helpful. We try to get to the heart of the matter and put how people really feel on the table. Then—even if there are emotions—we take a caucus. We go for a walk. We have people talk it through one-on-one or in groups. Sometimes people get really pissed off and decide they don’t want to be on the bargaining team anymore. But we have guidelines when we’re trying to reach consensus that we all sign off on, so there are expectations about how we treat each other. It sounds a little corporate, and it is, but we’ve put our staff through something called Radical Candor, which is about trying to talk to people directly. We do a lot of education with our staff around communicating, listening, and being okay with disagreement. If we’re winning, it’s going to feel very chaotic, but our member-leaders have the tools they need to fight fair.

Lewis: How has the debate about immigration changed among workers since you joined the labor movement? Is there an example you can think of when you’ve seen a worker change their mind?

Guenther: There’s always been a problem with racism and anti-immigrant rhetoric, but I felt like we were making advances in building a multiracial, multi-generational, multi-gendered front. Now we have slipped back quite a bit. And many labor leaders are afraid. I went to the People’s March in D.C. [on January 18], and I thought I was going to see all my labor friends, but nobody was there. We’re headed toward a fascist or conservative period of time, and I’m hoping that we can at least stop the fascist part.

When I meet Republican members—and all my family are Republican—I keep listening and I keep talking and I keep having conversations. And people do sometimes say: “You know what? You changed my mind.” Or, “I hear what you’re saying.” Or, “You treated me with respect, even though I completely disagree with you and you disagree with me.” I think it requires constant listening to see if there’s something that can bind us together. I try to appeal to people’s humanity. I think it’s the only way forward.

Iber: What do you make of the Republican Party’s attempt to brand itself as a more working-class party?

Guenther: I grew up in very rural eastern Oregon. I didn’t have access to a television, so I didn’t see the news very much, but there was radio. And Rush Limbaugh was on it, poisoning everybody’s minds. I remember thinking, “My community is getting rotted out by this.” The floor was falling out on logging, but they spun it and blamed it on [efforts to protect] the spotted owl, which was so bizarre to me.

I am so sick of billionaires having two parties and workers having none. People say Biden was the most pro-labor president. Oh, really? He’s the most pro-labor president, who chose to not step down so that we could have a real primary—and now Trump is the president? No thank you. I know there are good Democrats. And I think there are some good Republicans. But overall, both parties are too owned by money to be good advocates for working people.

In Poverty, by America by Matthew Desmond, you can see the rates of poverty don’t change whether the president is a Republican or a Democrat. They just hold steady. And if there’s poverty, that pulls down workers’ wages. There are dips, like during COVID-19, but the parties are not solving problems that workers care about. So I am not satisfied with either party.

Lewis: Do you have advice for other people in the labor movement about how to conquer some of the information that’s coming from the Rush Limbaugh types?

Guenther: No matter how white a workforce is, there are people who are affected or who are married to somebody who is affected. Stories change hearts. One-on-one conversations change minds. You’re not going to do a big town hall and get screamed at; that’s not going to help you. Go and find your people who are empathetic to the position and center them. Center their stories, and keep building out. You can start with five people who will come with you to meetings and who will push back and say, “Hey, well, that’s not how I experienced that,” or, “My grandfather and my grandmother immigrated here.” Every single person, whether they’re white or a person of color, has a story about how their family immigrated here, and a lot of it was through war and starvation. Our histories are actually quite similar.

We have a stagnant labor leadership who are afraid to talk to their own members, who got their unions from their daddies, who are getting their pension and their healthcare. They’re not movement builders. We need to clean up the labor movement, just as much as we need to clean up our political parties. We’re trying to reform the UFCW. If you’ve been in office for more than ten years and you can’t figure out how to talk to your members, it’s time to step aside. Let somebody else lead.

Lewis: How is the reform effort going?

Guenther: UFCW really doesn’t want to be the union that advocates for low-wage workers and takes on corporate America, but someday that will change. It’s either going to change soon or it’s going to change later, but it’s going to change. Because low-wage workers, grocery store workers, healthcare workers, frontline workers—they know that they kept this country going during the pandemic, and they are coming for what they deserve. They are going to expect more from their unions.

Faye Guenther is president of UFCW Local 3000.

Patrick Iber and Natasha Lewis are co-editors of Dissent.