Disenfranchisement: An American Tradition

Disenfranchisement: An American Tradition

Invoking the specter of voter fraud to undermine democratic participation is a tactic as old as the United States itself.

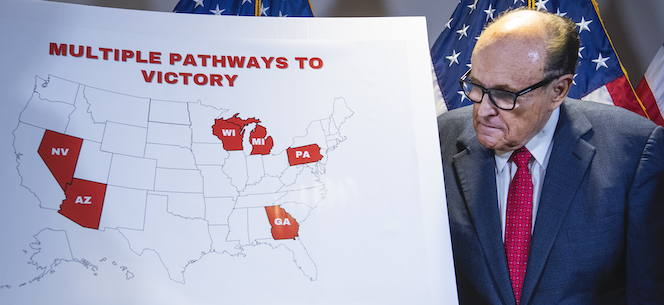

During the 2020 election, liberal pundits and politicians repeatedly warned that democracy was “on the line,” “at stake,” “in peril,” and facing “an existential threat.” There was occasion for the hyperbolic language: Donald Trump and his Republican allies orchestrated an unprecedented assault on the integrity of U.S. elections by, to list just a few examples, promulgating ludicrous lies about voter fraud, obstructing early mail-in voting, encouraging vigilante voter intimidation, and constricting access to polls. But critics risk succumbing to a liberal version of “Make America Great Again” nostalgia if they assume Trump’s departure from office will solve our democratic crisis. His efforts to maintain power built upon a long history of political exclusion and racial subordination in the United States. It is not surprising that politicians, if allowed, would prefer to pick their own voters. The more vexing question is why voter suppression is not more taboo in a country that extols its democratic system as a beacon for the world.

This election has exposed a broad ambivalence about (and from some quarters, outright disdain for) majoritarian, multiracial democracy. Candidates compete on a playing field designed over generations to protect capital, colonial ambitions, and white supremacy. The anti-majoritarian Senate and Electoral College have rightly come under harsh scrutiny this election cycle. But contests are also distorted by the nation’s gerrymandered districts, a campaign finance system that licenses wide-scale legalized corruption, and immigration and naturalization policies that dictate which residents must live and work under laws that they have no voice in shaping. Millions more are disenfranchised due to incarceration and felony convictions, or because they lived in Washington, D.C., Guam, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, or the Northern Mariana Islands.

Trump’s voter suppression efforts drew on currents in U.S. political culture that sanction this status quo. Politicians have been zealously using election regulations to sculpt the electorate since the earliest days of the republic. Elites protected their power by diluting or excising altogether the votes of subordinated groups, particularly African Americans, Indigenous people, the poor, women, and immigrants. To do so, lawmakers have barred voters on the basis of race, gender, character, language, literacy, property ownership, pauperism, tax-paying status, mental competency, felony conviction, and failing to properly register to vote. The architects of these policies often presented voting as a privilege—not a right—that can be revoked or restricted to cultivate a virtuous electorate. These restrictions, they argued, ensured the “purity of the ballot box,” the “integrity of the electorate,” and protection against voter fraud. And they often blurred the threat of illegally cast ballots with the alleged dangers posed by nonwhite, unfit, or uncivilized voters.

In popular memory, these practices finally ended with the 1965 Voting Rights Act. But despite the civil rights movement’s monumental victories, the battles to shape the electorate have raged on. Charges of voter fraud and tweaks to election and registration administration, which had always played a role in pruning the electorate and suppressing the Black vote, took on increased importance after lawmakers and courts confiscated more nakedly antidemocratic tools. People could not legally be disenfranchised on the basis of fixed characteristics such as gender or race, but they could still forfeit their vote through choices—most importantly, by breaking the law, but also by failing to register to vote by a certain date or lacking proper identification or skipping multiple elections in a row (which can result in being purged from the voter rolls). Fair elections require clear regulations and standards, but bureaucratic hurdles inevitably depress participation by disadvantaged groups. And they have often been deliberately constructed—as an appeals court found in 2016—to “target African-Americans with almost surgical precision.”

As overt barriers to the franchise fell in the 1960s and millions of Black Southerners joined the electorate, overall political participation plummeted. In the 1970s and 1980s, barely above half of eligible voters participated in presidential elections, and only around 40 percent in midterm elections. Some analysts debated whether dismal turnout reflected public apathy, alienation, or satisfaction with the status quo. Others shifted the focus from non-voters’ psychology to the structural barriers they faced: how voter registration regulations and voter-roll purging unevenly depressed turnout, skewing the electorate to overrepresent affluent whites.

Attempts to address these concerns were met, at every turn, with charges of voter fraud. Congressional Democrats introduced postcard registration legislation repeatedly throughout the 1970s. The policy would allow individuals to register by mail, bypassing local registrars’ notoriously inconvenient locations and limited hours. Opponents raised the risk of fraud, and the legislation failed to gain traction.

President Jimmy Carter’s attempts at electoral reform met a similar fate. In 1977, he proposed abolishing the Electoral College and instituting same-day registration for all federal elections, which would permit citizens to both register and vote at the polls on election day. The four states that had implemented election day registration saw increased turnout in a period of national declines and reported negligible irregularities. Still, the Carter administration, anticipating that charges of fraud would be the opposition’s principal strategy, preemptively added identification requirements and harsh fraud penalties to the bill. It was to no avail. Republicans and some sympathetic Democrats invoked the threat of voter fraud to kill the bill.

Many involved in these debates acknowledged the partisan motivations for preserving a shrunken electorate. One conservative strategist warned that same-day registration was “a satchel of pure political dynamite that could blow the Republican party sky high.” Democratic Vice President Walter Mondale conceded that even some members of his own party saw little incentive to push for a dramatic expansion of the electorate. In a memo to President Carter, he lamented, “There is, unfortunately, no real constituency for this bill.”

After these dead ends, activists turned to agency registration. These “motor voter” laws required that state agents offer people applying for a driver’s license or social services the opportunity to register to vote. In the 1980s, scholar-activists Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward embraced agency registration as a strategy to counter Ronald Reagan’s assault on the welfare state, hoping that registering public assistance beneficiaries would alter the demographics of the electorate and force politicians to more aggressively defend the interests of state workers, low-income people, and communities of color. Their organization, the Human Service Employees Registration and Voter Education Fund, joined with civil rights, community action, and voting rights organizations (and later “Rock the Vote”) to push for registration reforms at the state and federal level throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. Because officials would be registering people already affirmatively identified by the state, organizers hoped the policy would be insulated from concerns about voter fraud. But the specter of fraud continued to haunt the debate. Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell campaigned tirelessly against the law, sarcastically dubbing it “auto-fraudo,” while arguing that “relatively low voter turnout is a sign of a content democracy.” President George H.W. Bush vetoed motor voter legislation in 1992 on the grounds that it was “an open invitation to fraud and corruption.” When President Bill Clinton finally signed the law in 1993, fraud concerns had rationalized the inclusion of new voter list maintenance requirements and the elimination of election day registration.

Political elites with a vested interest in limited participation have bequeathed us with a maze of seemingly apolitical technical regulations—restrictive registration policy, limited poll locations, constrained absentee and early voting—that the Trump administration seized upon in their efforts to undermine the 2020 election. These mechanisms are best understood as growing out of old status tests for political rights, tools used to guard not just against unlawful votes but unwelcome, particularly Black, voters.

If there is anything positive to come out of Trump’s harrowing assault on U.S. elections, perhaps it will be a popular reckoning with the long-standing systemic opposition to majoritarian rule, full political participation, and universal adult suffrage. Building on the struggles that have expanded early voting and same-day registration in many blue states, House Democrats are pushing federal reforms to ease registration, limit voter roll purges, restore the gutted Voting Rights Act, and restrict felon disenfranchisement. Republicans will oppose these reforms and champion additional restrictions by invoking the dangers of fraud. Countering these charges will take more than pointing out the lack of evidence of voter fraud or introducing harsher penalties. It will require undermining the racially stratified notions of citizenship that such claims rest upon—and looking beyond electoral reform to the greater democratization of public life. That might mean self-determination for all permanent residents—regardless of their citizenship status, criminal record, or the territory where they reside—or the extension of democratic control into new arenas, such as workplaces, economic policymaking, media, and community safety. Ultimately, the most pressing question to arise from the 2020 election may not be whether our democracy can survive Trump, but whether the public supports an egalitarian and multiracial democracy.

Julilly Kohler-Hausmann is an Associate Professor of History at Cornell University and author of Getting Tough: Welfare and Imprisonment in 1970s America. She is currently writing a history of U.S. democracy since the 1965 Voting Rights Act through the lens of nonvoters.