A Simple Ethos

A Simple Ethos

The implementation of socialism is dauntingly complex, beset on all sides by historical forces and individual corruption. But I’m still a socialist because it is a way to be a human among humans, a person in a society of the people.

The following is part of a series of essays, “Why I’m (Still) a Socialist,” in our Fall 2022 issue.

“So, what’re you going to do with the money?” the radio host asked. “£10,000 is a lot of cash.”

It was July 4, 2015, and I’d just won the Caine Prize for African Writing for my short story, “The Sack.” This was my first interview of the night, over a hotel phone. I was the first Zambian to win the prize, so we’d mostly discussed that. This final question was sort of a throwaway and so was my reply.

“Oh, I split the money with the other four shortlisted writers.”

“What?!”

There was a stop-the-presses moment while they scrambled to keep me on the line. Really?! But why would you do that?! This soon became the lede. In the weeks of interviews that followed, reporters and readers demanded that I explain myself. I tried to unravel my reasoning, which had sat like a knot in my chest—firm if tangled—when I’d first decided that, in the unlikely event that I won the prize, I would share the money with the other writers. I had a full-time job as a professor, so I would do it in part because I could. But this wasn’t meant to be an act of philanthropy or generosity; it was an act of rebellion! Mutiny! In the aftermath, I detailed how I felt about the condescending imperialist vibe of the Caine Prize, how I bucked at the way people had been bluntly placing bets on us five writers. “Like horses! To our faces!” I exclaimed. “And did you know John Berger split his Booker Prize with the British Black Panthers and gave a speech about how ‘extensive trading interests in the Caribbean’ financed the Booker empire?”

My own acceptance speech announcing the split had been pithier and less pugilistic. After my thank yous, I’d said something like “writing is not a competitive sport,” stated simply that I was going to split the money, then invited the other writers to share the stage with me. As we all climbed down, an editor friend embraced me, tears in the corners of her eyes. A former shortlistee approached to shake my hand. “Someone finally did it,” he said with a grin. Whatever did he mean? “Oh, every year, all the writers say they’ll split the prize if they win! But no one ever does it.” (I’ve proven to be the exception/dupe in the years since, as well.) A prize administrator cut in to admonish me: “This’ll be a logistical nightmare!” she said. I apologized and promised to take care of the bank transfers myself. Outside the venue, I found myself apologizing again, to one of the prize judges this time, for mooting their hard work. She chuckled wryly over her cigarette. “You know it won’t make any difference, right?”

When I spoke to my family that night, I apologized to them, too. During the ceremony, they had been sitting in the dark, in the middle of a typical power outage in Lusaka. They had seen the news on Twitter on my older sister’s cell phone. As soon as she picked up my call, I heard ululations and applause over the spotty WhatsApp connection. My sister triumphantly reminded me that she had predicted my win, then passed the phone around.

“I’m sorry,” I burbled to my mother. “I know it’s not financially wise.”

“It’s brilliant!” she said, laughing. “After all, we are socialists here in Zambia.”

Socialism is obviously more sophisticated than “split the money.” But my mother was right. Apologetic as I am about it, my decision—and my subsequent ones, like donating prize money to bail funds for protesters, splitting the fee for a short story I wrote among the unpaid interns at the magazine that published it, giving back or splitting the money for any prize with a shortlist—can be seen as an expression, however oblique, of my upbringing as a Zambian socialist. Which is to say, it is far more about spirit than practicality.

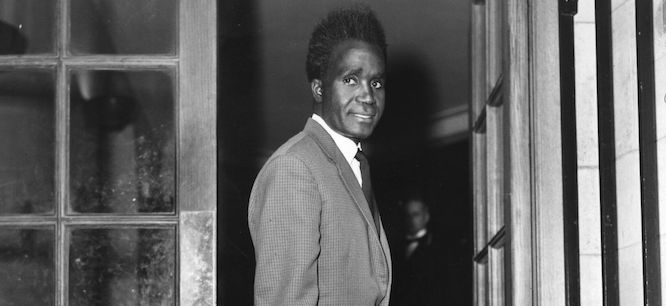

Zambia achieved independence from the United Kingdom in 1964. Our president, Kenneth Kaunda, was a mission-educated, teetotaling, guitar-playing, bicycle-riding school teacher who became famous for the white hanky he kept on hand to dab at his eyes whenever he fell to weeping. But Kaunda was also a freedom fighter. Ejected from colonial military service after one day (“I think news must have reached the army that we were ‘undesirable’ characters”), Kaunda had joined the independence movement known as the Cha-cha-cha campaign. This buoyant name disguises somewhat its tactics of direct action and civil disobedience: beyond protests and boycotts, roads and bridges were bombed to “make the imperialists dance to our tune.” (Violence would also become part of his transition to the presidency: on the very precipice of our first independence day in 1964, Kaunda sent state troops to quash a zealous communitarian religious sect, Alice Lenshina’s Lumpa Church, that was refusing to pay taxes and threatening to secede; about 1,000 people died.)

Once his United National Independence Party (UNIP) was elected, Kaunda made clear that Zambia would be nonaligned in the Cold War’s ideological and literal battles, and the country soon became a safe haven for other freedom fighters, regardless of their stated politics, from African nations that had yet to break free of colonialism. This rejection of both sides—a dwelling in the double negative that characterized many black intellectuals in this era—spurred Kaunda to pursue a new political theory. He wanted a worldview that neither centered itself around money and individualism, as capitalism did, nor dehumanized the human in the name of an abstraction (as the director of UNIP’s Research Bureau in the mid-seventies put it, “ideology is not the servant of man but his master in a communist society”).

Kaunda called his philosophy Zambian humanism. It was influenced by Christianity but also by his precursors in African socialism: Ghanaian Kwame Nkrumah’s “consciencism” and Tanzanian Julius Nyerere’s “Ujamaa.” All of these philosophies centered on the idea that one could derive a political theory from African cultural norms. For Kaunda, these included, as the scholar Alex Sekwat summarizes, “egalitarianism; inclusiveness; acceptance; mutual aid; man-centeredness; respect for human dignity; hospitality or generosity; kindness; hard work and self-reliance; communalism; cooperativism; political leadership as trusteeship; and respect for age and authority.” Kaunda’s alternative model hoped to eradicate the atrocities of colonialism and capitalism while remaining compatible with a traditional way of life, which was perhaps naively conflated with a “classless society conceived of as the natural state of Africa before the arrival of colonialism.”

The subsequent “indigenization” of public and private sectors, a term for an initiative to introduce trained Zambians into positions previously held by colonial officers and foreign subjects, chimes with this sense that Zambian humanism was a home-grown political philosophy. Translated into policy, it was meant to entail greater social security, increased state control of the economy, higher electoral participation, free education, free medical services, infrastructural expansion, and rural and agricultural development. It also aimed to do away with exploitation, abuses of power, corruption, and injustice—or, as a Nigerian political scientist paraphrased Kaunda’s rhetoric, to promote “a peaceful and just future for all Zambians under the leadership of UNIP.”

The actual viability of Zambian humanism is debatable. You might have guessed one of the problems: Kaunda remained president for nearly three decades. He had once proclaimed that “society must ultimately serve men and their well-being, men do not exist for the state.” But in 1972, UNIP became the ruling party of the nation, which was declared a “one-party participatory democracy,” a bit of an oxymoron. Zambian humanists argued that government intervention was needed to ensure that people were effective participants in and beneficiaries of social democracy; state control was also deemed necessary to push out the foreign interests that continued to extract Zambian resources and redirect the proceeds for their own countries.

Another problem is that Kaunda’s framework, while legitimate on its own terms, grossly underestimated the growing pains of a nation moving from colonial governance to self-sufficiency. Sekwat contends that

reform measures intended to turn Zambia into a humanist society failed to materialized [sic]. Deepening economic crisis caused by heavy indebtedness, high inflation rates, flight of capital, cuts in foreign aid, sharp decline in copper prices in the world market, deterioration of general terms of trade, decline in donor assistance and foreign investments, and increased corruption and misconduct in the public service all combined to undermine the humanist-based egalitarian reform measures and ultimately the legitimacy of the UNIP government.

As this suggests, certain problems were out of Kaunda’s control.

Some of them were historically overdetermined by the legacies of colonialism, like a paucity of university graduates to take over jobs (there were fewer than 100 in the whole country upon independence). Others were economic: the oil crisis, inflation, the copper market. But the Zambian government also waffled over the decades about whether to get entangled with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, in turn refusing loans, accepting conditional ones, trying out market-based structural reforms, then suspending dialogue with the IMF altogether in order to try out an indigenous reform program.

My mother, an economist, was part of that last effort to develop our own industries. Kaunda wanted us to be fully self-sustaining, and for a while we managed to stave off more loan commitments and refuse imports from places like apartheid South Africa by making our own products. I was a kid at the time, and I still remember the Zambian-made soda and candy . . . and then the reports of empty shelves and bellies. The program didn’t last. Economic crisis ensued. When push came to shove, all of our well-meaning wavering had led to a loss of trust among the international donor and foreign investment community.

Kaunda signed a constitutional amendment undoing his one-party rule of twenty-seven years and stepped down in 1991, replaced via vote by Frederick Chiluba. Since then, we’ve seen a series of mostly smooth elections, a game of tag between privatization and corruption, the seemingly ineluctable ravages of widespread poverty and the HIV epidemic—and a continued struggle to achieve anything close to the higher aims of Zambian humanism.

In my story that won the Caine Prize—a future-set floating epilogue to my novel The Old Drift—the protagonists have grown old and are musing upon their revolutionary days. Back in the 2020s, back when they were in their twenties, they tried to start a political movement. As I detail in the book, it’s called the “SOTP”—an acronym derived from a typo on a traffic sign painted on the road, more of a drift from a decisive “STOP” than an opposition to it. Inspired by their respective grandmothers, who have each dabbled in their own way in the distribution of goods, the younger generation debates the best way to achieve their goals—liberalism, revolution, subversion? They land on a rally that takes advantage of the (science-fictional) surveillance tech being tested on Zambians in the novel. Irony descends: the rally is shut down by violent force, using that same surveillance tech, backed by neocolonial funds from the global superpowers that have merged into a putative “Sino-American Conglomerate.”

I’m not especially hopeful about the real geopolitical ambitions on either side of that hyphen. In that way, I still feel the Cold War double bind of black politics: neither capitalism nor communism will save us. I don’t believe socialism is a middle way between the two, though. Nor is it the most provably successful or convenient socioeconomic or political model—I suppose this is why I’m always apologizing for it. A shadow of futility trails my feelings about socialism. But nowadays, it seems nearly impossible to resist the force of neoliberal capitalism, which is loud and everywhere and voracious; it swallows up everything, including our very resistance to it. Zambian humanism as a socialist philosophy still feels to me like a way to slip or stray from that thunderous logic.

Its Zambianness, for me, doesn’t lie in our so-called “traditional way of life,” but rather in our cosmopolitanism, what the historian Jodie Yuzhou Sun calls “the pragmatic and eclectic nature of Humanism,” and what I would call a radical embrace of contingency—which is also an embrace of the human, who famously “errs” by default. Zambia’s history is plagued by arbitrary arbitrations between competing powers, by violent and grievous errors. But the notion of syncretizing different cultures and ideas, of dancing with chance, at least as an ideal, was built into it at its birth in 1964: when the Union Jack was lowered and our green, red, black, and orange flag was raised, foreign-born Northern Rhodesians automatically became Zambian citizens.

In writing The Old Drift, I depicted one of those instantly minted citizens, a British-born woman, Agnes. One day, she stumbles into a meeting of “Reds” on the campus where her husband works:

She adored the ooh sound of the African socialist concepts from Tanzania and Kenya—uhuru and ujamaa and ubuntu, words for freedom and family and humanity. She believed in all those things, too. It was so obvious that they were true and good, especially . . . when applied to the actual oppression of actual people, the Bantu. Agnes quizzed [her maid] about her cultural beliefs. What was it like to be Bantu? To come from an ancient tribe so naturally inclined to socialism that its name simply meant “people”?

This is Zambian humanism as a kind of resonant sound, a name, a spirit.

The implementation of socialism is dauntingly complex, beset on all sides by historical forces and individual corruption—the same could be said of capitalism! But it is quite simple as an ethos. I’m still a socialist because it is a way to be a human among humans, a person in a society of the people.

Namwali Serpell is a Zambian writer and a Professor of English at Harvard University. She is the author of Seven Modes of Uncertainty (Harvard University Press, 2014), The Old Drift: A Novel (Hogarth, 2019), Stranger Faces (Transit, 2020), and The Furrows: An Elegy (Hogarth, 2022).