Will the Teachers Take Control?

Will the Teachers Take Control?

No group is better positioned than organized teachers to force Washington to develop a national plan to deal with the pandemic.

On August 3, 1981, federal air traffic controllers in the United States launched an illegal strike, grounding flights from Guam to Puerto Rico. President Ronald Reagan walked into the Rose Garden that morning to deliver an ultimatum: unless they returned to work within forty-eight hours, the controllers would be fired. While few contemporary observers immediately grasped its significance, that confrontation soon led not only to defeat for the controllers—who were permanently replaced when they defied Reagan’s order—but to disempowerment for American workers generally. Following Reagan’s example, private-sector employers made the 1980s synonymous with strikebreaking and union-busting, initiating a decades-long labor retreat.

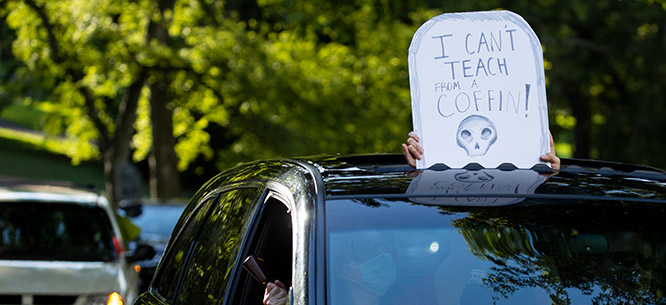

We might soon witness a similarly momentous showdown. Today, thirty-nine years to the day after the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike began, teachers across the nation are staging a National Day of Resistance demanding safe schools. Their protest is every bit as audacious as the 1981 strike, yet the teachers’ strategy, and the context behind their protest, could not be more different. The differences indicate both how much public-sector unions have learned from history and the crucial role their members are poised to play in pushing our leaders to finally deal seriously with this raging pandemic.

The controllers’ strike, even many of its most ardent supporters later conceded, was poorly conceived. It was an illegal walkout whose most important demand was a large across-the-board wage increase—a demand levied during a recession in which other unions were offering concessions. PATCO not only challenged a popular president, it made no effort to cultivate allies even in the AFL-CIO, after alienating union leaders by endorsing Reagan’s election a year earlier. Controllers believed they could win their fight alone—that they would never be replaced if they only stuck together. Their misjudgment was costly.

Today’s teachers will not make the same mistake. The central demand of the Day of Resistance is not a wage increase, but safe schools. Its impetus comes from local teachers’ unions in cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, and St. Paul that have embraced a far-sighted strategy of mutual support called Bargaining for the Common Good, which has now evolved into a network of the same name. Their members are not trying to shut down education, but rather to ensure that schools don’t reopen until they are safe for teachers, students, and their families. The protest enjoys the active support of parents and community allies, whose causes the teachers are embracing in turn. Teachers’ demands include a moratorium on evictions that threaten to upend their students’ lives and police-free schools where black lives matter. They are also attempting to stay the cruel hand of fiscal austerity that now hangs like a Sword of Damocles over school boards, states, and local governments, even as the fortunes of the wealthiest continue to balloon during the COVID-19 crisis. Their approach addresses head on the dynamics that have beset workers and unions since the Reagan era.

Just as the PATCO strike erupted out of years of festering labor conflict in the stagflation-beset 1970s, this Day of Resistance is the fruit of a decade of activism that has slowly reshaped public-sector labor—especially teachers’ unions—amid surging inequality. In the aftermath of the Great Recession and the election of labor foes like Wisconsin’s Governor Scott Walker, public-sector unions understood that their very survival depended on their ability to align their cause more closely with the communities their members served. In 2012 the Chicago Teachers Union helped show the way, joining with community allies and leading a successful strike against Mayor Rahm Emanuel in which they demanded schools that served Chicago’s children. That strike helped inspire the Bargaining for the Common Good model.

During the #RedforEd strikes of 2018 that erupted across West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, North Carolina, and Arizona, teachers spontaneously adopted that same logic, fighting as much for their students, communities, and working-class taxpayers as for themselves: the West Virginians refused to return to work until other government employees got the same raise they were offered, while the Arizonans demanded a tax on the wealthy. Embracing common good demands, teachers have almost single-handedly resurrected the strike after decades of dormancy. More strikers took to U.S. streets in 2018 than at any time since Reagan’s presidency—and a staggering 78 percent of them worked in schools.

While the Day of Resistance is not a strike, the recent decision of the American Federation of Teachers to authorize its state and local affiliates to walk out if their districts don’t take proper precautions suggests how quickly resistance could swell into a nationwide wave of teacher strikes—a possibility unimaginable only two months ago. If we fail to develop a response to COVID-19 that protects children, essential workers, and vulnerable (especially black and brown) communities, we might see strikes that channel and fuse the passions of both #RedforEd and Black Lives Matter. No group is better positioned to force Washington to finally develop a national plan to deal with this pandemic.

Ronald Reagan delivered a historic ultimatum thirty-nine years ago. We may soon see the teachers’ ultimatum—#EdEquityOrElse—as equally historic.

Joseph A. McCartin teaches history at Georgetown University, is the author of Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike that Changed America, and has written widely on Bargaining for the Common Good.