Who Passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964?

Who Passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964?

tk

LIKE SO many of my generation who did voter registration work in the South during the 1960s, I have been saddened by the debate that Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama sparked over whether Martin Luther King or President Lyndon Johnson was responsible for the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act that outlawed discrimination in hiring and public accommodations. Instead of providing voters with a thoughtful view of the recent past, Clinton and Obama combined to offer a crude, “great man” theory of history in which King’s vision and Johnson’s pragmatism were portrayed as antithetical forces.

The debate has quieted down. But it should not be allowed to fade from the headlines without a reminder of the lesson this controversy threatened to obscure—blacks and whites across America relied on one another to make the Civil Rights Act of 1964 a reality.

The act had its legislative origins in a June 11, 1963 speech that President John Kennedy delivered on national television after Justice Department officials, aided by federal marshals, forced Alabama Governor George Wallace to stand aside while two black students were admitted to the previously segregated University of Alabama. “If an American, because his skin is dark . . . cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place?” Kennedy asked the country.

But Kennedy’s speech, which was followed hours later by the murder of Mississippi civil rights leader Medgar Evers in Jackson, did not guarantee a speedy passage of civil rights legislation. A coalition of southern Democrats and conservative Republicans stood in the way and the best that Kennedy could do before his November 22 assassination was to get his civil rights bill voted out of committee.

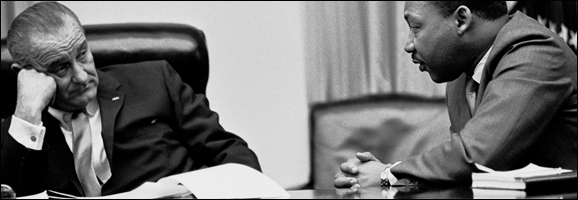

It fell to President Lyndon Johnson to get Kennedy’s civil rights legislation enacted. Soon after taking office, Johnson made his intentions clear. “We have talked long enough in this country about equal rights,” he told a joint session of Congress on November 27. “It is time now to write the next chapter and to write it in books of law.” At this same time, Martin Luther King was playing a crucial role in shaping public opinion. His April 16 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and his August 28 speech “I Have a Dream” galvanized millions of Americans who in the past had remained passive when support for civil rights was needed.

Still, it was not until 1964 that Kennedy’s civil rights bill got through Congress. On February 10, the House passed the bill by a vote of 290 to 130 and on June 19, in the wake of a record-breaking 75-day filibuster, which took up 534 hours, the Senate passed its version of the civil rights bill by a 73 to 27 margin. Now Lyndon Johnson began pressuring Congress to reach agreement on a bill that he could sign by July 4.

At this moment, Johnson benefited not only from the civil rights coalition led by Martin Luther King but from the grassroots work of Bob Moses, then a young organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) who had been active in Mississippi since 1961. At a November 1963 SNCC meeting, Moses had proposed a 1964 “Summer Project” in Mississippi that would make extensive use of college students, getting them to teach in freedom schools and carry out voter registration drives. A black-white coalition, Moses believed, would engage the whole country. But no sooner had the Summer Project begun when three of its participants—Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman—disappeared on June 21 near Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Their disappearance (their bodies would later be found buried in an earthen dam) could not be ignored by America. Television cameras and the print media descended on Mississippi while state officials acted as if nothing of importance had happened. “They could be in Cuba,” joked Mississippi Governor Paul Johnson.

It was the worst response that the diehard segregationists of the Deep South could have made. The influence of Martin Luther King, Lyndon Johnson, and John Kennedy, along with years of demonstrations and sit-ins, had created a political tide that reached its peak with the disappearance of the three men. On July 2, two days ahead of schedule, Congress, under heavy public pressure, agreed to the civil rights bill that Johnson wanted. Five hours later in a White House signing ceremony timed to coincide with the evening news, the president addressed the nation.

It was the worst response that the diehard segregationists of the Deep South could have made. The influence of Martin Luther King, Lyndon Johnson, and John Kennedy, along with years of demonstrations and sit-ins, had created a political tide that reached its peak with the disappearance of the three men. On July 2, two days ahead of schedule, Congress, under heavy public pressure, agreed to the civil rights bill that Johnson wanted. Five hours later in a White House signing ceremony timed to coincide with the evening news, the president addressed the nation.

“One hundred and eighty-eight years ago this week a small band of valiant men began a long struggle for freedom,” Johnson told the nation. “Now our generation of Americans has been called on to continue the unending search for justice within our own borders.” The analogy was unmistakable. The president was comparing the work of the Founding Fathers with that of the civil rights movement.

Martin Luther King, who was present at the White House signing ceremony, also had no doubts about the significance of the day or about Lyndon Johnson’s role in making the civil rights bill law. “It was a great moment,” King declared, “something like the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln.”

Today, we cannot know exactly what Johnson and King, two coalition builders, would say about the efforts to portray them as civil rights rivals. But it is hard to imagine that both would not have seen comparisons that pit them against each other as inimical to the civil rights movement they believed in. As King observed of the struggle for racial justice in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail”: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.”

Nicolaus Mills is a professor of American Studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Like a Holy Crusade: Mississippi 1964—The Turning of the Civil Rights Movement in America and most recently, Winning the Peace: The Marshall Plan and America s Coming of Age as a Superpower.