Two Decades After the Fall: Is Social Democracy Dead?

Two Decades After the Fall: Is Social Democracy Dead?

Two Decades After the Fall: Anna Seleny

TO PARAPHRASE Mark Twain, reports of the death of social democracy in Eastern Europe are greatly exaggerated—or, at the very least, premature. The neoliberal rhetoric of the early transition years is history. Even at the time, it revealed more about the disgust with the corruption and repression of state socialism than a clear choice between the relatively freewheeling U.S. market and the European social market model. Eastern and Central European economies have either retained or adopted new forms of social protection not unlike those of their western neighbors. They are still evolving however, and stand to varying degrees on the unstable political and economic ground of the partially reformed institutions of the old regime.

In the context of the EU and the ever-expanding Euro-zone, it’s easy to forget that institutional reform takes time even in highly developed democracies. But the former Soviet bloc countries faced the unique challenge of tackling political and economic reform simultaneously, and five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, eminent economists and political scientists were still predicting that it would take at least three decades for Eastern Europe to “catch up” to the West.

But twenty years on, even a casual visitor would find such views quaint. The prognosticators were much too pessimistic; this was most evident in the case of privatization, which proceeded faster than anyone expected (even if the results, especially in terms of corporate governance, varied widely). And in retrospect, nobody fully appreciated the impact of the EU, which began to exert indirect influence on Eastern Europe even as merrymakers hacked away at the Berlin Wall. Today, the Baltic states and most of Eastern Europe are fully consolidated democracies with functioning market economies; through 2007, the region was growing at 1-2 percent faster, on average, than its western neighbors.

These achievements are all the more remarkable when considered in an international context. If the political and economic challenges were not enough, the former state-socialist nations–with their under-developed financial markets and still-evolving legal infrastructures–came to the market in an era of explosive globalization and unfettered international capital flows.

Some countries faced additional constraints. Poland and Hungary had heavy international debt burdens in 1989. While Hungary was able to put off the day of reckoning thanks to significant reforms made in the 1980s and before, Poland essentially defaulted, and only shock therapy forestalled a spiral of hyperinflation. Czechoslovakia was luckier. It had very low international debt and was poised to re-establish the trade ties it had with Germany from the first half of the twentieth century. Bulgaria and Romania had no international debt but were considerably less developed than the Central European countries and suffered more serious un- and underemployment.

Given the shared challenges of their transition away from communism and their integration into an increasingly global economy, it’s not surprising that we can find at least some areas in which the thirty-year prediction was not far off the mark. Real incomes may not reach West European levels in some countries for at least another decade and none of the countries have yet completed the reform of their main redistributive systems.

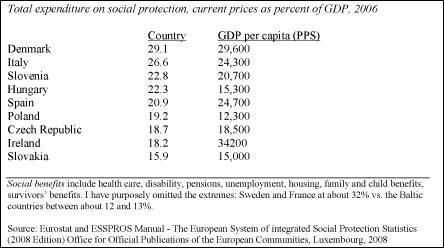

The economist Janos Kornai famously described East European countries as “premature welfare states” with entitlements out of all proportion to GDP and the fiscal capacity of the state. In Central Europe, welfare spending is in fact broadly comparable to some of the older European democracies, despite the fact that the Eastern economies are still significantly weaker in virtually all respects.

There can be no doubt that social democracy works best in wealthy countries, and that the significantly lower per-capita incomes of most of the East European countries does not augur well, in the short term, for the consolidation of social democratic policies and institutions. But some core social democratic values are widely held in the region.

There can be no doubt that social democracy works best in wealthy countries, and that the significantly lower per-capita incomes of most of the East European countries does not augur well, in the short term, for the consolidation of social democratic policies and institutions. But some core social democratic values are widely held in the region.

The Sociologist Zsuzsa Ferge refers to surveys from Eastern Europe and also from the 2002 European Social Survey to show that the “culture” of welfare is not very different in the West and the East. In both West and East, the demand for the state to provide health care is on the order of 90 percent of all respondents; and the percentage of those who want the government to take steps to reduce income inequality is comparable in Eastern Europe (84 percent in Hungary and Slovenia, and 80 percent in Poland) and Western Europe (80 percent in Spain, 79 percent in Italy, 90 percent in Greece, and 89 percent in Portugal). Countries scoring lower on this value can also be found in both the East and West (53 percent in the Czech Republic and only 43 percent in Denmark).(1)

To be sure, the welfare systems of Eastern and Western Europe developed in dramatically different ways. In the West, social protections grew up organically over “a long gestation period with the creation of ‘common social property’ (essentially social insurance based on strong labor rights) as a counterpart to private ownership,” whereas in the East, “socialist dictatorship found a tragically opposed solution to the dilemma of assuring security to non-owners by abolishing private property altogether.”(2)

Eastern Europeans who lived through that “solution” are deeply cynical about politics, and this legacy presents a serious obstacle to the strengthening of a social democratic ethos. Many voters cannot see past the fact that the region’s social democratic parties are often led by repackaged former communists. A few years ago Jurgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida argued that “Europeans have a relatively large amount of trust in the organizational and steering capacities of the state…[and] maintain a preference for the welfare state’s guarantees of social security and for regulations on the basis of solidarity.”(3) The second half of the statement applies to most Eastern Europeans, too; but not the first. Eastern Europeans do not trust their politicians and are cynical about the political process. This may pose as much of a challenge to social democracy as the relative weakness of the region’s economies. Even so, the surveys cited above point to other legacies of the state socialist era—such as a preference for low income inequality—that offer, at least, a qualified hope for social democracy.

Anna Seleny teaches at Tuft University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

(1) The percentages reflect those who “strongly agreed” and “agreed” taken together. See Zsuzsa Ferge, “Is there a specific East Central European Welfare Culture?”, in Peter Herrmann, ed., Governance and Social Professions: How Much Openness is Needed and How Much Openness is Possible (New York: Nova Science Publishers 2008), Table 8 p. 176.

(2) Ibid. p. 177.

(3) Habermas, J. and J. Derrida (2003) ‘February 15, or What Binds Europeans Together: a Plea for a Common Foreign Policy, Beginning in a Core of Europe’, Constellations 10 (3): 291-7.