Scapegoats in a City Under Siege

Scapegoats in a City Under Siege

The Central Park Five is a powerful reminder of what can happen when innocents are caught up in racial divisions and tensions they didn’t create and railroaded for a crime they didn’t commit, and when all of the city’s institutions collaborate in the horrific act.

On one level, the New York of the late 1980s was a crack-ridden, violent city, where garbage overflowed the curbs, garish graffiti engulfed the subways, homelessness was epidemic, and houses sat abandoned. I always looked over my shoulder while uneasily walking the Manhattan streets at night. I know these images create an oversimplified, tabloid version of the city of that period. There were many intact, thriving white ethnic and black working-class neighborhoods like Astoria and St. Albans. New York was also a city of big money, with booming financial markets and real estate development (though the 1989-92 recession was beginning to hit the housing market hard, with the city ultimately losing one-tenth of its jobs) and a flourishing high culture. It was still an exhilarating place to live for someone who loved urban rhythms and cityscapes. Though the city could feel threatening and the dangers were real, they were only one part of New York’s story. But the sensational nightmare image of decay and crime dominated the way most Americans perceived New York.

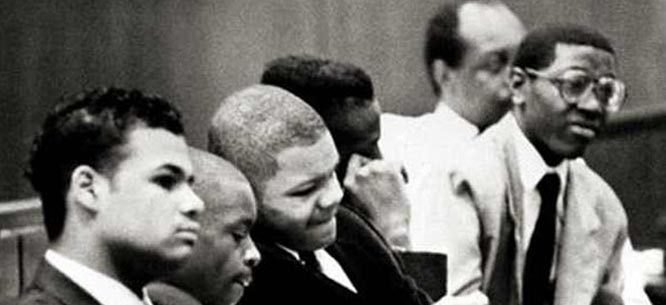

That chaotic, violent New York of 1989 is the social context for Emmy Award–winning documentary filmmaker Ken Burns’s new film—directed and written in collaboration with his daughter Sarah Burns (author of the book The Central Park Five: A Chronicle of a City Wilding) and her husband, David McMahon. The documentary explores the arrest and trial of five black and Latino teenagers from Harlem. They were arrested for the rape and vicious beating of a Central Park jogger, who was not expected to survive the crime though she miraculously did. The jogger, Trisha Meili, a twenty-eight-year-old Wall Street investment banker and Yale University business school grad, was a white, upper-middle-class resident of the Upper East Side—the perfect victim for the police, courts, media, and public to sympathize and identify with, while the perpetrators, on the surface, fit the stereotypes of menacing kids who could commit such a heinous crime. (In 1989 there were close to 1,900 murders in New York, many of them committed by adolescents.) The case had a special resonance in a city wracked by racial tension.

The film is like a procedural, scrupulously detailing how the incident began with a loose-knit group of five boys—part of a crew of thirty to fourty teens who violently erupted into the park one evening from their East Harlem neighborhood, harassing bikers and joggers and causing general mayhem. Their behavior—ranging from adolescent macho stupidity to criminal activity—led the press to create the buzzword “wilding” for the actions of these so-called uncontrolled “wolf packs.” The police rounded up a number of teenagers, but only these five were held for the rape and near-deadly assault of the jogger. The other boys were given short sentences for additional crimes or sent home.

These five boys were, in Burns’s words, easy targets. “They had never been in the system…they were the most vulnerable to police tactics. They wanted to please, and they wanted to go home.” Held for days, and exhausted by the interrogation process, the boys were manipulated and frightened into providing confessions to the police, though there was no other evidence against them. The confessions themselves were filled with contradictory statements, inconsistencies, and a timeline that made little sense. In addition, their parents did not have the wherewithal to deal with the workings of the judicial process once it got underway.

The film conveys just how loaded the trial was against the five: they had inadequate defense lawyers and a tough judge, and they faced daily alarming bold headlines revving up racist feeling and public antipathy toward them. They were turned into scapegoats in order to assuage the public’s fear of and anger about runaway crime. The police and prosecution wanted to close the case quickly, so they could claim they were successfully dealing with the problem.

The five boys—Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, Yusef Salaam, and Kharey Wise (who was hard of hearing and developmentally challenged)—spent between six and thirteen years in prison for a crime they didn’t commit. In prison they rejected all plea bargains. It was only more than a decade later, in 2002, that Matias Reyes confessed to the rape, as well as a series of other rapes and assaults across the city. All the accumulated evidence supported his guilt, including the advanced DNA and forensics evidence. The boys’ convictions were overturned, and in 2003 they filed a multi-million-dollar federal lawsuit for malicious prosecution, racial discrimination, and emotional distress, which still remains to be settled. Clearly, the police found it easier to commit a profound injustice than to take responsibility for their transgressions—an admission that would hurt their careers. In Burns’s words: “This strikes us as just another effort to delay and deny closure and justice to these five men, each of whom was cleared of guilt even though they served out their full and unjustified terms.”

The Central Park Five is much narrower in focus and much more objective in tone than most of Burns’s other work. But like all his films, it deals with a prime aspect of the American experience: in this case, how major American institutions dealt with a racially charged case at a time when residents of New York felt, justifiably, under siege.

Burns achieves this by skillfully blending archival footage, including the original videos of the case (some shot by the police); interviews with the boys, now men in their late thirties; and commentary by people involved in different ways with the proceedings—politicians, journalists, a social psychologist, and even a member of the jury—like David Dinkins, Ronald Gold, LynNell Hancock, Michael Joseph, Saul Kassin, Ed Koch, New York Times reporter and columnist Jim Dwyer, and historian Craig Steven Wilder.

Wilder puts forward the undeniable truth that the public’s concern and rush to judgment would have been much diminished if it was a non-white, inner-city woman who was raped, while Dwyer suggests that the wrongful convictions were the result of a lot of people not doing their jobs, in a profoundly divided city. Even liberal columnist Bob Herbert, writing in 2002 after Reyes’s confession, maintained that “We pronounced them guilty the first time we ever heard of them, and they remained guilty, until now.” An understandable response, given the climate of the time, but it indicates how reflexively most New Yorkers, liberals and conservatives, reacted to crimes of this nature.

Burns’s film stirs moral outrage by showing just how much of the five men’s lives were stolen from them. The boys were victims of a system that treated them as disposable objects. And when released, none of them have had an easy time adjusting—finding it impossible to recover lost time, and struggling to live like ordinary people.

They are rightly angry about what they have endured. The most articulate, Yusef Salaam, states: “It feels great to have a voice now that’s not proceeded by animal, wolf pack, or any of those other derogatory, colorful statements.” Burns, however, does not delve deeply enough into their personalities to differentiate them, since he’s more interested in them as social victims than as flawed individuals. We could have gained greater understanding of who the boys are if, for example, the film had decided to examine more closely what they had done in the park that night. Burns, however, wants to make the most potent case for them that he can, and the film achieves just that—resonating both morally and emotionally with the viewer.

The city is clearly a different place today. Crime is radically reduced, and the streets feel more secure and cleaner. The graffiti plague is no more, and there are few abandoned houses. But as the city has gotten wealthier and more gentrified, it has become one of the most unequal places in the nation. And though racial tension has abated, the police (who are much more racially and ethnically integrated) continue to face minority protests. The controversy over the police department’s stop-and-frisk tactics has divided the city along racial lines, with most whites seeing it as a way to improve public safety, while the majority of blacks and Latinos feel it leads to the harassment of innocent people. Of course, of the 700,000 stops made by police last year, about 85 percent involved blacks or Hispanics, with few resulting in arrests, and fewer still for non-drug-related offenses. If the police are less brutal and racist since the days of the Central Park Five, major and minor incidents continue to occur. Burns’s film is a powerful reminder of what can happen when innocents are caught up in racial divisions and tensions they didn’t create and railroaded for a crime they didn’t commit, and when all of the city’s institutions collaborate in the horrific act. It was an urban tragedy.

Leonard Quart is the coauthor of American Film and Society Since 1945 and a contributing editor at Cineaste.