The Renminbi’s Rollercoaster

The Renminbi’s Rollercoaster

As China’s economic prospects darken, headlines worldwide accuse China’s leaders of threatening global capitalism. Once upon a time, that was precisely the point.

As China’s economic prospects darken, headlines worldwide have accused China’s leaders of threatening global capitalism. Once upon a time, that was precisely the point. Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong dismantled capitalism at home after he founded the People’s Republic, and soon began fomenting socialist revolutions abroad. Mao hated money itself. The founder of the People’s Republic would send occasional sums to old comrades in need, but refused to touch any tender himself. Once, “he threw aside a bill pouch as if he had accidentally picked up a toad,” wrote an aide. The Chairman ordered, “Take it away! I never touch money.” Then he mused: “Money is such a wretched thing, yet I don’t know how to get rid of it. No one has managed to, not even Lenin.” Pending money’s abolition, Maoist China made do with renminbi, Mandarin for “the people’s currency.”

The renminbi has come a long way since, a reflection of China’s epochal economic transformation since Mao’s death in 1976. Last November, the International Monetary Fund tapped “the People’s Currency” to join its Special Drawing Rights, the elite currency club of global capitalism. The “redback” has arrived: in IMF ledgers, it now rubs shoulders with the euro, yen, pound, and U.S. dollar. But Chinese market shocks of recent months have global markets wondering if even this largely symbolic step was premature. In hindsight, the renminbi’s ascension to the SDR looks like a rare bright spot amid economic troubles that are roiling global markets and taking China’s currency for a ride.

This year, Chinese markets have continued to wobble. In January, regulators discontinued the trading “circuit breaker” that was meant to have curbed such volatility, but they have since sought to clamp down in other ways, hardly reassuring global investors. Early this year, the Party imposed stricter capital controls to stem an outflow of money from China into safer markets. As a result, the renminbi, a currency that the IMF certified as “freely usable” as a precondition of joining the SDR, is less convertible to hard currency today than it was in November.

This predicament would have been hard to foresee when China’s first communist tender was minted in guerrilla bases in the early 1930s. Its pulpy notes bore a grimacing Lenin and the characters “Bank of the Chinese Soviet Republic.” Chiang Kai-shek, leader of China’s ruling Nationalist government, sent armies to crush the insurgents.

The Communists spent two decades on the run, minting outlaw money as they went. Mao and his comrades settled in the remote northwest, running a rival state out of caves hewn into the mountainside.

The Second World War ravaged China. Japan’s defeat renewed the civil war, bringing Weimar-like inflation and gold hoarding. Ordinary Chinese trusted only gold, American greenbacks, and, occasionally, old Mexican silver dollars.

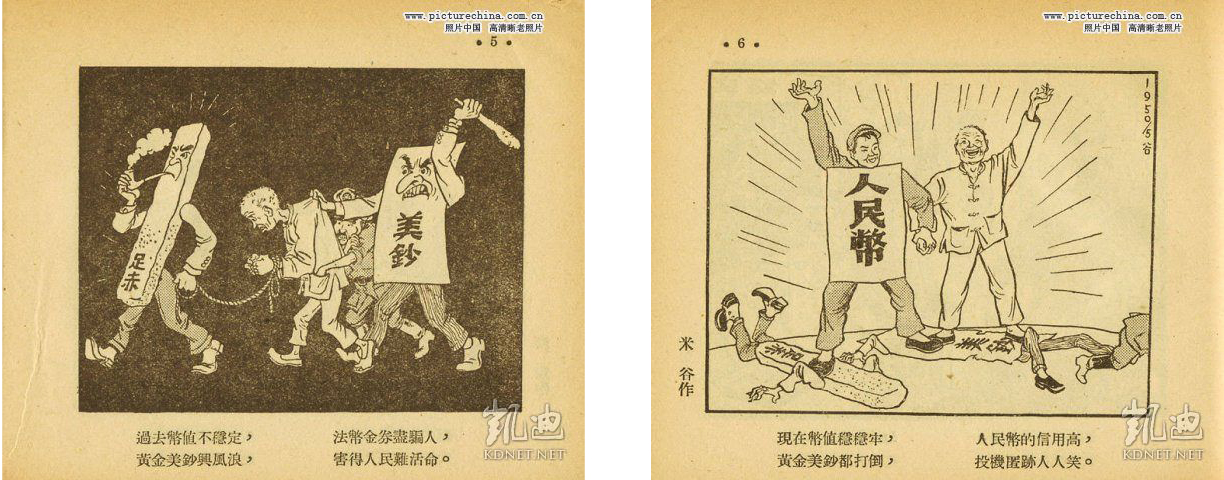

When Mao’s Communists won the civil war and established the People’s Republic in 1949, stabilizing prices was a priority. In 1950, a cartoon collection called “Liberation: Before and After” put two panels on its cover. The “Before” panel showed a Chinese peasant led in shackles by Gold, whipped from behind by U.S. Dollar. The “After” panel had a new character: a Mr. Renminbi beaming triumphantly at the grateful peasant, stomping “Gold” and “Dollar” beneath his boots.

Mr. Renminbi was resolutely proletarian. Bills displayed tractors, iron forges, soldiers, farmers, dams, harvests. Mao vetoed proposals to put his own face on the currency, even during the Cultural Revolution, when China revered him as a living god and stamped his likeness everywhere. After touching the money packet, recalled the aide, Mao “wiped his hands as if they had been soiled,” and repeated: “I never touch money. Remember that!”

China’s Communist Party has since conveniently forgotten Mao’s aversion. In 1999, the Chairman appeared on a redesigned hundred-Renminbi bill. Its new color was the flushed pink of a wild salmon, cooked rare. The nickname “redback” has stuck since.

A steady purge of non-Mao notes continued through the aughts, down the ranks of denominations. During a 2004 summer language program in Beijing, I noticed that only the old one-yuan bills remained. Flattening one on a classroom desk, I laid it out next to a crisp new note. The old bill was brown, with mountain tribeswomen on one side and the Great Wall on the other. The crisp new bill was pea green and had the same moonfaced Mao as every other denomination.

In Beijing, we learned to ask the bank for wads of jiao bills—a tenth of a yuan—to have something for crowds of beggars outside our campus gates.

One weekend, in Shanghai, I was surprised to notice one-yuan coins. Coins circulate better than bills: they jangle in pockets, pop into the slots of vending machines. One-yuan coins soon began to percolate in Beijing too. The panhandlers preferred them to tattered jiao notes; soon, a fistful of jiao wouldn’t even buy an egg pancake.

In more remote suburbs, vendors sometimes made change from the past. The old fifty-yuan bill displayed the socialist trinity: peasant, worker, and intellectual, with rosy cheeks so chiseled they could carve a Peking duck. Further out in the countryside, one spotted the occasional a one-fen note: worth a hundredth of a yuan, a sixth of a U.S. cent.

Older expatriates told tales of the nineties, when it was illegal for foreigners to use renminbi. Outsiders in China lived in the currency apartheid of Foreign Exchange Certificates, accepted only at dingy “Friendship Stores” and “Friendship Hotels” in larger cities. The system was abolished in 1997.

Less than a decade later, one could spot foreigners using renminbi outside China. In the market square of a Mongolian border town, I was mobbed by black marketeers eager to trade renminbi for Tögrög. (An estimated 60 percent of currency circulated in Mongolia is now Chinese.) Later, a Manhattan bank clerk gladly switched my Mao bills back into dollars, but stared blankly at a wad of Tögrögs stamped with Genghis Khan. I regretted leaving my redbacks at the border.

North Korea, which extracts visitors’ hard currency to bolster the regime, changed its cash system in the early aughts, allowing tourist shops in Pyongyang to take renminbi alongside euros and yen.

On Taiwan, an island ruled for decades by the communists’ bitter enemies, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party, RMB are now accepted from visiting mainlanders. Mao and Chiang, two former foes, are now cheek to cheek in the cash registers of Taipei tourist shops, Chiang on New Taiwan dollars and Mao on mainland tourists’ renminbi.

Renminbi also filtered into Hong Kong, the proudly free-market former British colony that is now an autonomous enclave of the People’s Republic. First, currency exchange stands traded renminbi for Hong Kong dollars. Then, cashiers at upscale boutiques and dim sum joints started taking them. Soon ATMs began dispensing renminbi along with Hong Kong dollars, and customers could open renminbi accounts. Offshore renminbi, used to denominate bonds and settle payments, began to clear through Hong Kong. Then Singapore, Paris, and London.

At the dawn of this decade, boutiques on London’s Bond Street and the Champs-Élysées began accepting the redback from eager crowds of Chinese tourists. Zimbabwe, its own currency sunk by hyperinflation and its government budget kept afloat by aid from Beijing, made the renminbi legal tender late last year. Some analysts hailed the renminbi as a rival to the dollar.

Most, though, find reports of the greenback’s demise exaggerated. The renminbi’s recent berth in Special Drawing Rights is essentially symbolic, and has been largely forgotten amid recent market turmoil and currency uncertainty. SDR status acknowledges China’s bulk more than its currency’s parity with the legal tender of rich democracies. Moreover, Beijing’s bankers didn’t have much time to bask in the SDR’s propaganda prestige. They still answer to a Party leadership that is opaque, mercurial, and unswervingly “puts politics in command.” Two recent bouts of market turbulence show just how true this Maoist aphorism remains, and how quickly promises—of an orderly normalization of China’s money, a progression away from capital controls and other market interventions, of the redback’s ever-freer convertibility—can be forgotten when the Party’s monopoly on power is threatened.

Last June, China’s overheated stock market swooned. By July, its gyrations had wiped out ten times the value of Greece’s GDP. The Party snapped into action as only a Leninist state can. It canceled IPOs by fiat and forbade brokerages from selling shares, as nearly half of all listed companies suspended share trading for days. The People’s Bank of China gave direct loans to state-backed financial institutions to buy shares, and commercial banks joined in. In August, Beijing staged a surprise devaluation of the renminbi, its biggest negative value shock since 1994. By month’s end, dozens of “malicious speculators” and “rumor-mongers” were under arrest. A financial journalist who had vanished into the hands of state security resurfaced on China Central Television, confessing to market sabotage and “spreading panic.” Some state media darkly hinted that foreign investors with a “hidden agenda” were manipulating markets. A propaganda slogan went viral: “There is a war to protect A-Shares! Join the fight if you can; if you have no bullets, lend your voice!” Patriotic propaganda keyed up nationwide.

Market volatility calmed in the fall, only to flare up again in the first weeks of 2016. This time, stock market shocks could not be explained away as bursting bubbles in a relatively small and speculative casino unrelated to the broader economy. China’s once-in-a-century economic miracle is coming to an end. GDP growth is at its slowest in over two decades, and China’s financial commissars are resorting to increasingly draconian measures to prevent capital flight out of the country, reversing policies intended to internationalize the yuan. Meanwhile, foreign financiers like George Soros have smelled blood and are betting that China’s slowdown will hurt its neighbors’ economies and currencies, likely devaluing the renminbi in the process. The propaganda machine has ratcheted up again: last month, editorials in People’s Daily and the official Xinhua News Agency blasted “radical speculators” and said that “Soros’s attacks will not succeed . . . have no doubt of that.”

The jargon was up to date. But the Party’s distrust of money and markets, determination to put politics in command, and xenophobic paranoia—these are still pure Mao.

Nick Frisch is an Asian studies doctoral student at Yale’s graduate school and a resident fellow at Yale Law School.