Recovering the Progressive Frederick Douglass

Recovering the Progressive Frederick Douglass

In the face of this barrage of conservative appropriations, the time has come to set the record straight and recover the progressivism of Frederick Douglass.

Each Black History Month, there is plenty of discussion of Frederick Douglass, the slave-turned-abolitionist who is remembered as one of the greatest figures in African-American history, and whose legacy remains a source of conflict. To the chagrin of many progressives, a number of scholars and public officials claim that Douglass’s political philosophy “lives on” in the ideas of contemporary conservatives.

Each Black History Month, there is plenty of discussion of Frederick Douglass, the slave-turned-abolitionist who is remembered as one of the greatest figures in African-American history, and whose legacy remains a source of conflict. To the chagrin of many progressives, a number of scholars and public officials claim that Douglass’s political philosophy “lives on” in the ideas of contemporary conservatives.

In the wake of the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the U.S. Supreme Court, for example, political theorist Stephen Macedo wrote an essay in the New Republic arguing that Thomas is best understood as part of a tradition of black conservatism that began with Douglass. Macedo was not the first—or the last—to claim that Douglass’s philosophy of self-reliance has a certain resonance with familiar right-wing tropes. In On Hallowed Ground, intellectual historian John P. Diggins contended that there is a tradition of African-American thought “stretching from Frederick Douglass to Booker T. Washington to our contemporaries Shelby Steele and Thomas Sowell” that “emphasizes liberal individualism based on initiative in the private sphere, self-development, work and thrift, the rationality of economic life, personal responsibility, and integration with the larger white society.” Historian Jonathan Bean took to the pages of National Review to argue that “Douglass’s timeless vision of America celebrates both national and individual independence, in sharp contrast to the culture of entitlement and infantile dependence on the government’s management of our economic and personal affairs.” Justice Thomas himself has used some of his judicial opinions as vehicles to defend the “Douglass to Thomas” thesis.

In the face of this barrage of conservative appropriations, the time has come to set the record straight and recover the progressivism of Frederick Douglass.

In Grutter v. Bollinger, the 2003 case in which the Court upheld the University of Michigan Law School’s affirmative action program, Justice Thomas began his dissenting opinion with Douglass’s words:

[I]n regard to the colored people, there is always more that is benevolent, I perceive, than just, manifested towards us. What I ask for the negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice. The American people have always been anxious to know what they shall do with us. . . . I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are worm-eaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall! . . . And if the negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone! . . . [Y]our interference is doing him positive injury.

“Like Douglass,” wrote Thomas, “I believe blacks can achieve in every avenue of American life without the meddling of university administrators.” If Thomas is to be believed, Douglass is best understood as an anti-paternalist libertarian. His message to would-be benefactors is, leave us alone! But this interpretation is deeply flawed.

First, it is important to make sense of what Douglass meant by “let him alone.” In context, it is clear that Douglass’s words were aimed at a very different target than what Thomas has in mind: “If you see a negro wanting to purchase land, let him purchase it. If you see him on the way to school, let him go; don’t say he shall not go into the same school with other people. . . . If you see him on his way to the workshop, let him alone; let him work. . . . ” When Douglass said “let him alone,” he was demanding that both state and non-state actors allow African Americans to exercise their legitimate rights without interference.

Second, Douglass always coupled his command to “let him alone” with a demand for “fair play.” For Douglass, fair play meant that the social and economic rules were not rigged in favor of or against any particular group. He believed that government had a vital role to play in ensuring that individuals were relatively free to participate in the marketplace, and were not subject to systematic attempts to prevent them from making economic progress (as was the case, for example, with sharecropping).

At a certain level of abstraction, both conservatives and progressives accept the idea that government should play this role, but differ on precisely how this role should be carried out. But a second idea encapsulated in Douglass’s understanding of fair play undermines a conservative reading of his legacy: he believed that government should take aggressive action to level the playing field. In an 1894 speech on “Self-Made Men,” which is a favorite of contemporary conservatives, Douglass makes this point clear:

It is not fair play to start the negro out in life, from nothing and with nothing, while others start with the advantage of a thousand years behind them. . . . Should the American people put a school house in every valley of the South and a church on every hillside and supply the one with teachers and the other with preachers, for a hundred years to come, they would not then have given fair play to the negro. The nearest approach to justice to the negro for the past is to do him justice in the present.

Third, Douglass’s political beliefs go against the arguments offered by conservatives like Thomas that government programs to assist those in need—the agenda of what Thomas calls “the benevolent state”—are rooted in “an ideology of victimhood” that undermines the dignity and self-respect of those they are intended to help. Although Douglass was always sensitive to the impact of policies on the self-respect of beneficiaries, and on outside perceptions of those beneficiaries, he did not accept the contemporary conservative way of thinking. In 1886, Douglass reflected on the challenges still confronting blacks in the South. Of the “emancipated class” in Mississippi, he said:

They need and ought to have material aid of both white and colored people of the free states. A million dollars devoted to this purpose would do more for the colored people of the south than the same amount expended in any other way. There is no degradation, no loss of self-respect, in asking this aid, considering the circumstances of these people. The white people of this nation owe them this help and a great deal more. The key-note of the future should not be the concentration, but diffusion [and] distribution. This may not be a remedy for all evils now uncured, but it certainly will be a help in the right direction.

All of this makes clear that Douglass’s rhetoric, while sometimes individualist, was always coupled with sensitivity to circumstances. In certain contexts, he believed, a simple pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps philosophy was woefully inadequate.

WHILE THE conservative reading of Douglass is deeply flawed, it retains some truth, which scholars on the left have often overlooked. There is perhaps no better example of this tendency than the interpretation of Douglass offered by the late Wilson Carey McWilliams, one the greatest students of American political thought. In his magnum opus, The Idea of Fraternity in America, McWilliams argued that Douglass’s experience as a slave led him “close to a true recognition of human weakness and dependence” and to an understanding “that what is really to be feared in human affairs is isolation.” Douglass, McWilliams argued, was “devoted to the ideal of human fraternity” and saw that the “principal antagonists” of this ideal are “those who accept individualism and the doctrine of self-reliance, for these must necessarily be fearful of their fellows.”

While McWilliams was right that Douglass’s experiences as a slave led him to a deep appreciation of the myriad ways we rely upon one another to survive and flourish, Douglass did not accept the view that the doctrine of self-reliance was at odds with the idea of fraternity. He believed that practicing the virtues of self-reliance, industriousness, sobriety, integrity, orderliness, and a desire for self-improvement was the most promising path to both independence and, perhaps paradoxically, assimilation into the community. In an 1886 speech on the “progress of the colored race,” he said:

We have but to toil and trust, throw away whiskey and tobacco, improve the opportunities that we have, put away all extravagance, learn to live within our means, lay up our earnings, educate our children, live industrious and virtuous lives, establish a character for sobriety, punctuality, and general uprightness, and we shall raise up powerful friends who shall stand by us in our struggle for an equal chance in the race of life.

Douglass believed individuals could “raise up powerful friends” by striving to be self-reliant. In other words, rather than seeing the ethos of self-reliance as deleterious to the bonds of community, Douglass thought of it as a crucial step in building up the respect individuals have for one another.

THESE CRITICISMS of the flawed attempts by Thomas and McWilliams to appropriate Douglass’s ideas should not be read as a general condemnation of all attempts to cull wisdom from the great statesmen and citizens of the American past. Douglass has many important lessons to teach us, but our attempts to learn from him ought to be chastened by a heavy dose of humility. More than one hundred years have passed since Douglass’s death, and we cannot know how the ensuing years would have altered his understanding of the world.Perhaps the closest we can come to capturing the spirit of Douglass’s political philosophy in our time is to adopt the critical disposition he endorses in an essay he wrote in 1860 entitled, “The Prospect in the Future.” In that essay, he lamented the fact that “narrow and wicked” selfishness allowed Americans to proclaim their love of liberty while at the same time denying basic rights to so many human beings. Douglass wanted to resolve this “terrible paradox” by convincing Americans to move from “the downy seat of inaction” and replace their narrowness with egalitarianism, their selfishness with humanitarianism. In those moments when we are willing to ask ourselves how “narrow and wicked” impulses haunt our love of liberty—and when we ask how to close the gap between the ideal of liberty and the realities that surround us—we come closest to acting as the legitimate heirs of Frederick Douglass’s political project.

Nicholas Buccola is an assistant professor of political science at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon. His book, The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass: In Pursuit of American Liberty, will be published by New York University Press in April.

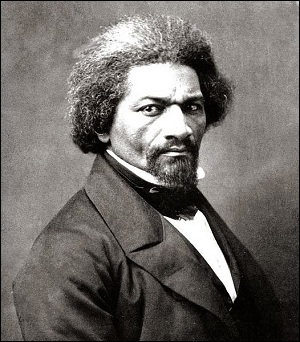

Photo: Douglass c. 1866, Collection of the New York Historical Society, via Wikimedia Commons