One Death, Myriad Resurrections: In Search of the Historical Jesus

One Death, Myriad Resurrections: In Search of the Historical Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth was not the first or last to preach against empire, but he is the only revolutionary whose story has held such sway over millennia.

Radical Jesus: A Graphic History of Faith

Paul Buhle, editor; Sabrina Jones, Gary Dumm, Nick Thorkelson, artists; Laura Dumm, colorist

Herald Press, 2013, 128 pp.

Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth

Reza Aslan

Random House, 2013, 296 pp.

Killing Jesus: A History

Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard

Henry Holt and Co., 2013, 293 pp.

When I was a middle schooler I found Fulton Oursler’s fictionalized account of the Gospels, The Greatest Story Ever Told, much easier to read than the archaic language of my confirmation-class King James Bible. Although over-written and full of too many blue-eyed denizens of Galilee, Oursler’s classic tells a gripping story of resistance and transformation, one familiar to the 2.1 billion people who claim Christianity as their religion. The sixty-five-year-old book remains in print and is still selling well in paperback. Chances are, though, that the buyers are quite a bit older than I was when I found it under the tree one Christmas morning. They’re probably not in the demographic that checks “none” when religious affiliation comes up on forms.

It is this demographic that historian Paul Buhle hopes to reach with Radical Jesus: A Graphic History of Faith, which brings together politically engaged graphic artists Sabrina Jones, Gary Dumm, and Nick Thorkelson to tell political stories of the faith. The first is of a Jewish peasant who inspired his followers with parables about equality and justice and who urged them to feed the hungry, comfort the broken-hearted, heal the sick, and resist oppression. The text follows the biblical narrative, with more emphasis on Jesus as a reformer within Judaism than as an opponent of empire.

The images on the page remind us of the story’s contemporary relevance, with Wall Street bankers strutting by beggars, a Dick Cheney–esque devil tempting Jesus in the wilderness, and modern-day soldiers arresting Jesus against the Jerusalem skyline. The Sermon on the Mount is juxtaposed with pictures of union organizers, nonviolent protesters, anti-foreclosure activists, prisoners, and victims of gun violence. Not surprisingly for a book published by a Mennonite press, the stories chosen for this anthology trace a red line of nonviolent dissent through the ages: Jesus from pagan Rome, the Protestants from Christian Rome, pacifists from other Protestants, Catholic priests and nuns from their bishops. The book’s dedication reads, “To those many Christians who have sacrificed their lives, across two millennia, for the causes of peace and justice.”

From the Lollards to the Anabaptists to the Quakers to the abolitionists to the civil rights movement, from the anti–Vietnam War movement to the base communities of Latin American liberation theology, to the Plowshares movement against nuclear weapons and the Christian Peacemaker Teams in war zones, Buhle and co. offer vignettes of what we could loosely call the Social Gospel, although not all the people described would put themselves in that camp. (And many who do believe in the Social Gospel do not subscribe to the pacifism or strategies of the more modern movements chronicled here.) The graphic rendering serves as a valuable introduction to these movements, especially the earlier ones, many of which are little known outside of fairly small circles. Even the stories that are better known, such as those of the nonviolent abolitionists and supporters of the civil rights movement, often ignore the religious roots from which the participants drew nourishment.

Here, the protagonists’ faith is front and center. On one page, we see the home of Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth being bombed the night before the kick-off of a campaign against segregated buses in Birmingham, Alabama. Lying stunned in the ruins, a miraculously alive Shuttlesworth quips, “Now that’s what I call being saved.” In the next frame, reporters ask if he’s going ahead with the campaign. When he says yes, they ask, “Didn’t that bombing teach you anything?” and he answers, “I wasn’t saved to run.”

In Radical Jesus, nobody runs. They witness, they persevere, sometimes they despair, but they keep on. Too often, they die for the faith.

Is it worth it? When one person is released from twenty-seven years in jail for a series of symbolic acts of resistance, a fellow activist says, “27 years?!? And what do we have to show for it?” Another responds, perhaps quoting one of the Berrigan brothers, “Jesus never told us to be successful, only to be faithful.”

The preachers of today’s “prosperity gospel” might disagree. And they would not be alone in doing so. Just what Jesus really told his followers ranks among history’s most vexed questions, and it’s gotten even more airtime than usual in recent months thanks to two books about the historical Jesus that appeared around the same time as Buhle’s compilation: Zealot, by Reza Aslan, and Killing Jesus: A History, by Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard.

The Iranian-born Aslan, who is associate professor of creative writing and cooperating faculty in the department of religion at the University of California–Riverside, has written the most ambitious account of the three—a gripping story of a brutal empire and the people who tried, unsuccessfully, to oppose it. This empire not only tortured and killed many of the revolutionaries who battled it, but later co-opted the religion developed by the followers of its most famous opponent and thus defeated him in death as well as in life. (Many progressive Christians date the distortion and subsequent decline of Jesus’ message from 330 CE, when it was adopted by the Roman emperor Constantine, but Aslan puts it earlier still.)

In Aslan’s telling, Jesus is an illiterate revolutionary who, with his followers, defied Rome and died an insurrectionist’s public, painful, and humiliating death. The effort to overthrow Caesar, who called himself the Son of God, by one who mocked him by using the same name came to a blood-soaked end not at Calvary but in 70 CE amid the ruins of Jerusalem, with the failed insurrection of the Zealots, which led to near-annihilation of the Jews and of those who preached Jesus’ message among the Jews. And that message, Aslan contends, was nationalistic and revolutionary, not inclusive and metaphorical.

Aslan claims that the destruction of the Temple and of Jerusalem traumatized the Jews into giving up on revolution. Those who preached the revolutionary, non-collaborationist message of Jesus had either already been put to death or died in the subsequent slaughter. Paul, who had been in conflict with others about how enthusiastically to seek converts outside of Judaism, was in Rome at the time and was now free to reinterpret the message as one of personal salvation rather than physical liberation and to seek more followers among the Gentiles (read, Rome). It’s not a new thesis, but Aslan’s deft writing makes it a page-turner. And although the very human historical Jesus of Aslan’s telling is not quite the same as the “radical Jesus” who has inspired major social movements, the two have more in common with one another than with the beatific blond personal savior of much of mainstream Christianity.

Last September, a few months after Aslan’s book skyrocketed in sales (largely because of a Fox News interview in which the interviewer claimed that Aslan, as a Muslim, had no place writing about Christianity), conservative news commentator Bill O’Reilly’s Killing Jesus: A History hit the stands. O’Reilly and his co-author, Martin Dugard, with whom he also wrote Killing Lincoln and Killing Kennedy (two other figures for whom the book market never seems to be saturated), present a conventional biblical narrative as if it were a groundbreaking account of historical facts: a man named Jesus preached a gospel of love and was put to death because he opposed both the ossification of his own religion and the yoke of Rome. His body disappeared after his death and has never been found, but his prophecies about the destruction of Jerusalem came true, and he has inspired millions throughout the last two thousand years. He did this with “no infrastructure . . . no government behind him.” He is a lone actor against the forces of organized religion and an oppressive state.

Much as they claim to be dealing only with a historical Jesus, the reverence O’Reilly and Dugard show for the Gospels as, well, gospel truth, belie their claim. They have, however, brought to a conventional story the intrigue of a thriller. Each chapter ends with the cliffhanger that takes you to the next page. When John the Baptist is beheaded, we read, “Jesus of Nazareth has one year to live.” After the interview with Pilate, “The scourging pole waits.”

Ignoring the last sixty-five years of biblical scholarship, O’Reilly and Dugard tell much the same story as Oursler did in The Greatest Story Ever Told, but with less character development and more torture porn. We learn more than we want to know of the proclivities of the Romans, whose depravities were only hinted at in Oursler’s more innocent age.

More insidiously, Killing Jesus repeats the anti-Jewish tropes of the Gospels. After paying lip service to the oppressed Jewish population’s view of Pilate as villain, O’Reilly and Dugard remind us: “But one of their own is just as guilty.”

Aslan’s corrective on this point is invaluable. If the Jewish establishment had been set on punishing Jesus for blasphemy, he stresses, they would hardly have needed Pilate’s approval; they could easily have stoned Jesus to death on their own, as they later did to many of his followers. The responsibility, then, lay with the brutal Pilate, who probably never even saw Jesus before his death and would barely have glanced up from signing a death warrant if he had. For Aslan, the lasting notion that the Jewish establishment was implicated in Jesus’ death is largely attributable to his later followers, who softened the story for the large Gentile population among whom they hoped to win converts.

Aslan notes that John

adds one final, unforgivable insult to the Jewish nation that at the time was on the verge of full-scale insurrection, by attributing to them the most foul, the most blasphemous piece of pure heresy that any Jew in first-century Palestine could conceivably utter. When asked by Pilate what he should do with “their king,” the Jews reply, “We have no king but Caesar!”

“Thus,” Aslan concludes, “a story concocted by Mark [probably the earliest writer] strictly for evangelistic purposes to shift the blame for Jesus’s death away from Rome is stretched with the passage of time to the point of absurdity, becoming in the process the basis for two thousand years of Christian anti-Semitism.”

Aslan gives us a historical Jesus shorn of all mysticism and mystery:

If one knew nothing else about Jesus of Nazareth save that he was crucified by Rome, one would know practically all that was needed to uncover who he was, what he was, and why he ended up nailed to a cross. . . . Jesus was executed by the Roman state for the crime of sedition.

It is an attempt that confirms much for the unbeliever and adds fascinating insights for the believer. However, it fails to convince this skeptical believer, compellingly written as it is. Aslan’s work has been attacked for its factual errors, but it is the theological conclusion that is so hard for many Christians to accept. Although he asserts that “Jesus the man is every bit as compelling, charismatic, and praiseworthy as Jesus the Christ,” there is nothing in this book to distinguish Jesus from other revolutionaries. There is nothing that would make his teachings stand out through the centuries, that would inspire those martyrs in Buhle and co.’s book and countless others. He was not the first or last to preach against empire, but he is the only revolutionary whose story has held such sway over millennia. Paul may well have twisted the message, as Aslan says, but it is not Paul who will be celebrated this Easter. At this point, two thousand years after the fact, it is perhaps impossible to separate man from myth. What will be celebrated is a story of victory over defeat as embodied in someone whose life continues to be interpreted and reinterpreted for each new age.

O’Reilly and Dugard do not ask why the story has such power. Their historical Jesus as presented in the Gospels is accepted on faith from the moment he steps on to their pages. He makes the transition from would-be messiah to the Christ practically in one weekend.

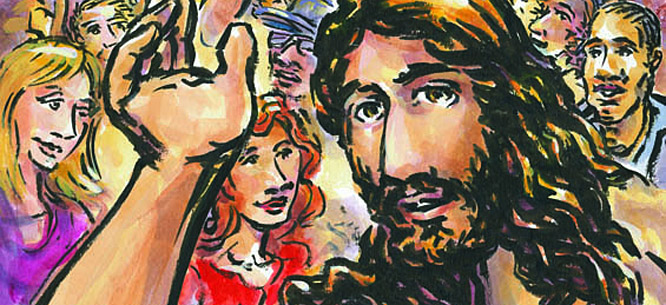

So, which Jesus do some of us take home this Easter? The covers of each of these books offer a pretty straightforward distillation of their competing narratives. Radical Jesus shows a traditional-looking but dark-haired, dark-skinned Jesus surrounded by a placard-bearing, multiracial crowd, perhaps on Wall Street, presumably protesting injustice. The point here is that this is not the “personal savior” or lone actor of conservative religion. This is a man who speaks and acts in community and whose message is constantly being reinterpreted in community. Aslan’s Jesus, painted during the Italian Renaissance, is a haunted-looking, wide-eyed enigma. He stares out at us. He is alone. O’Reilly and Dugard’s book jacket shows not a person but a blood-stained wooden cross, with the inscription, “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews” at the top. In a postscript, the authors pay tribute to the power of a message of love that inspired both Martin Luther King and Ronald Reagan.

O’Reilly and Dugard’s book has been in Amazon’s top one hundred for about thirty-two weeks. Aslan’s book is No. 505 at Amazon, though it had a stint, along with O’Reilly and Dugard’s, as the number one New York Times bestseller. Radical Jesus is at No. 529,743.

And that just about sums it up. Those of us who find Jesus of Nazareth’s concern for the poor, for equality, for justice (words that never appear in O’Reilly and Dugard’s narrative) to be compelling don’t get a lot of publicity or sell a lot of books. But we’re still here and have been since the stone—real or figurative—was rolled away from the tomb.

In claiming the story of Jesus, we find ourselves alongside right-wingers, left-wingers, middle of-the-roaders, the apolitical, and the ahistorical. But we don’t cede ground.

This Easter, even in my ultra-liberal Greenwich Village church, we’ll probably sing “Christ, the Lord, Is Risen Today,” our minister will finesse the Resurrection, and we’ll gather around tables for a shared Easter meal of abundance and community. We’ll hope for good weather to complement the symbolism of new life, of renewal both spiritual and political. But even if it’s raining, even if the cause of justice and equality seems stalled, we’ll break bread in memory of those who came before, in honor of those who still fight, and in hope for a truly new world to rise from the ruins of the old.

Maxine Phillips is editor of Democratic Left and former executive editor of Dissent. She is also former co-editor of Religious Socialism, the newsletter of the Religion and Socialism Commission of Democratic Socialists of America. Last fall she organized a book talk at her church for Radical Jesus that featured artist Sabrina Jones.