Disenfranchised by Debt

Disenfranchised by Debt

Court fines, fees, and restitution payments fund government operations—and hold millions of people in dire financial straits.

In the years she spent between 2002 and 2013 as a California Superior Court Judge in San Diego, Lisa Foster rarely paused when she issued a fine as part of a judgment. The courthouse ran like a production line, and her focus was on figuring out the details of custody and probation. “What we were taught is that your clerk would just hand you a number, and you would say, ‘fines and fees are this amount,’” she said in a recent phone interview. “It never occurred to me to think about the fines in relation to a person’s financial circumstances.”

One day she asked a clerk about the fine guidelines: was she absolutely required to mete out a certain amount for a given offense, or did she have discretion? The clerk didn’t know. Foster brought it up at a judge meeting. Again, no one knew—though the judges did establish that, between their courthouses, the variation in amounts seemed arbitrary. Foster led a local task force that consulted the relevant statutes and produced a standardized guide by which judges could determine what offenders should pay.

On the other side of the country, toward the end of Foster’s tenure on the bench, Marq Mitchell received a felony conviction in Florida after getting in a fight. Mitchell, who had been in and out of state custody since he was a kid, spent around two months in jail. He got out and returned to his life, but when he tried to renew his driver’s license, he found that it was suspended for failure to pay the debts he had accrued though his run-ins with the justice system. This was the first he had heard of his criminal debt, he said. He didn’t remember getting a bill in the mail, but he was often homeless and lacked a stable address.

Mitchell tried to establish a payment plan with courthouse officials, but he struggled to navigate the justice system, or even to figure out what he owed. Whether or not he had a license, sometimes he had to drive. But he tried to find work as close as possible to his residence in East Orlando—at a call center, or in the service industry. Commutes on the retrograde public transportation system could often take hours. Once, at about the same time Mitchell departed for his job at a Cracker Barrel in the south part of the city, twenty-seven miles away, his roommate departed for Jacksonville, 140 miles to the north. The roommate arrived first.

Though neither fully realized it at the time, Foster and Mitchell were experiencing the effects of a historic explosion in court-related debt, driven by sprawling fines, fees, and restitution payments. Public officials and private profiteers in local, state, and federal jurisdictions have offloaded the ballooning costs of running the criminal justice system from the general public onto the overwhelmingly poor people who “use” it.

This sprawling mechanism entangles poor and disproportionately black and brown Americans in the criminal justice system. For a long time, it went generally unremarked upon by society’s most powerful. But change is afoot. A nascent movement to curb or abolish court-related fees has emerged. Across the nation, from California, which just passed probably the most consequential bill yet in the effort to curb court-related debts, to Florida, where, in a high profile development, an appeals court recently ruled the state could prevent hundreds of thousands of ex-felons from voting because of their outstanding debt, the fight over how the criminal justice system should be funded is about not just fines and fees but the very structure of American society.

Court fines and restitution—punishment and victim recompense, respectively—have long histories in criminal justice. Fees to meet administrative costs are a more recent invention. In the late twentieth century, all three of these forms of legal financial obligations (LFOs) proliferated at a scale without modern precedent. In the 1980s, the federal government sought to cut spending and began to rescind its financial support of local and state governments. Meanwhile, a movement of “tax revolts” compelled local leaders to cap their own governments’ traditional sources of revenue.

These forces converged to create deep and persistent public budget crises in local jurisdictions, says Joe Soss, who discusses the matter in a forthcoming book, Preying on the Poor: Criminal Justice as Revenue Racket. Meanwhile, as local budgets dried up, the United States was becoming a world leader in its rates of incarceration, as aggressive discriminatory policing and an increasingly punitive legal code pulled millions of people, disproportionately poor, black, and brown, into the criminal justice system.

Criminal justice in the United States is generally administered—and funded—at the state and local level. And though the sprawling regime has usually been exempted from austerity plans, local governments have struggled to meet the rising costs associated with mass incarceration. In recent decades, public officials and managers have become more entrepreneurial. From park fees to increasing university tuition, new costs have proliferated throughout the public realm. But this dynamic played out with particularly acute force in the criminal justice system, where monetary sanctions could be instituted in the name of getting tough on crime.

Cash-strapped public officials also outsourced formerly public services to private companies, which pitched themselves as money-savers but actually just redirected costs onto the people compelled to use their services, according to one National Consumer Law Center report. A multibillion dollar “prison retail” industry emerged, charging exorbitant rates for phone calls, money transfers, and commissaries. Sentinel, a firm specializing in “offender management solutions,” boasts on its website that, as correctional agencies managed “ever-growing offender populations with ever-shrinking fiscal resources,” in 1993 it “created the first ever offender-funded electronic monitoring program.”

In local governments across the nation, market logic became “the air people breathed, the water they swam in,” Soss said in a phone interview. This ecosystem produced the “system that operates today, basically to siphon resources out of race- and class-subjugated communities and deliver them as revenues to governments and corporations.”

Some of these developments were codified into law. As Alexes Harris documents in A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Punishment for the Poor, in 1994 Arizona added a 57 percent “felony surcharge”—the percentage tacked atop a defendant’s baseline monetary sanctions. By 2012 the surcharge had reached 83 percent. Beginning in 1977, a person in Washington State had to pay $25 per felony conviction. Twenty years later they had to pay $500. Fines and fees were also assessed in an ad hoc manner in local jurisdictions around the country, often at the discretion of “street-level bureaucrats with little governmental accountability or oversight,” as Harris puts it.

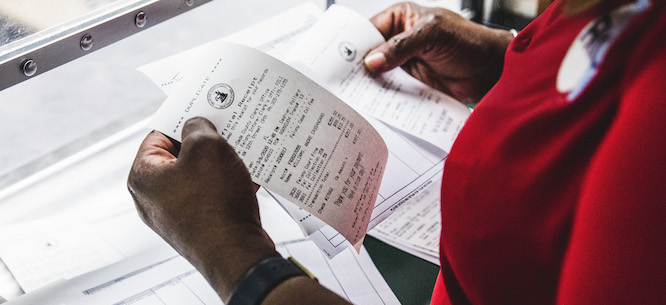

The debt incurred by these charges accrues at every step of a person’s path through the criminal justice system. In 2014 NPR found that most states charged offenders for public defenders and for room and board. A 2010 Brennan Center for Justice report includes a snapshot of one docket sheet, for which a defendant convicted of the intent to manufacture a controlled substance was charged $100 for “police transport,” an $8 “Postage Fee,” a $230 “service charge,” and $5 toward the “Firearm Education and Training Fund.” Her sentence included a maximum of twenty-three months in prison, a $500 fine, $325 in restitution, and fees amounting to $2,464.91.

The debts continue to mount during probation. A California legislative report found that, over three years, someone under high supervision—involving electronic monitoring or drug tests—might accrue $18,000 dollars in fees alone. Someone under low supervision might owe $3,000 in fees for the same period. The proceeds filter into the criminal justice system, but they also support a diverse and seemingly random array of government commitments. In California in 2015, beneficiaries of court-related fines and fees included the Oil Pollution Administration Subaccount, the State Dentistry Fund, and the Winter Recreation Fund.

When, as is frequently the case, debtors don’t or can’t pay, local jurisdictions apply pressure. Interest accrues. Collection fees mount. Harris documented the case of one Washington State woman who ended up with $33,000 in LFOs. She tried to make her payments; yet with interest she owed more than $70,000 a decade later. The New York Times reported in 2012 on the more ordinary case of Gina Ray, whose $179 speeding fine morphed into a suspended license, $1,500 dollars in debt, and jail time. In many states, license suspension for failure to pay outstanding debts—including those incurred from non-driving related offenses—has become routine. This can precipitate a monetary sanction vortex when the same person is then cited for illegally driving. Though debtors’ prison has long been banned in theory, in practice, it has not been uncommon for some authorities to issue arrest warrants for those believed to be willfully withholding court payments.

These local developments add up to a striking trend. While there is little national data available, federal agencies estimate that between 1985 and 2014, the sum total of outstanding legal financial obligations increased from roughly $260 million to $100 billion, affecting roughly 10 million people. This debt explosion went widely unremarked upon in mainstream discourse, even as, by the early 2010s, many governments were attempting to fund upward of 10 or 20 percent of their budget with court fines and fees. One such place was Ferguson, Missouri.

By the time Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown in August 2014, the swell of court-related debt had already made it onto some institutional radars. There had been litigation regarding debtors’ prisons and privatized probation programs in which companies directly charge fees to the probationers they oversee. The ACLU and NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice issued reports on fines and fees as early as 2010. “And basically no one cared,” said Mitali Nagrecha, who has been researching and writing on court-related debt for more than a decade. “No one thought it was a large, pervasive issue, and if they did [they thought] it was just in the South or something. Ferguson cracked that open.”

In March 2015 the U.S. Department of Justice published an investigation of the Ferguson Police Department, which found that the city leadership’s financial priorities had led many police officers “to see some residents, especially those who live in Ferguson’s predominantly African-American neighborhoods, less as constituents to be protected than as potential offenders and sources of revenue.” The document laid out this dynamic in granular and chilling detail and was covered widely in the media. The report’s impact derived from the way it “connected the fees and fines issue to how communities feel and experience the police,” said Nagrecha.

After leaving the bench, Foster took a job in Obama’s Justice Department, and she read the Ferguson report just before it went public. “I was profoundly disturbed,” she told me. It was clear that Ferguson was not an isolated case, and Foster spearheaded a multipronged Justice Department effort to address the court-related debt crisis. At the end of Obama’s term, Foster and Joanna Weiss, who previously worked for the Laura and John Arnold Foundation—a philanthropic outfit that has bankrolled much of the push for fines and fees reform—joined up to head the Fines and Fees Justice Center, which organizes information for researchers, activists, and journalists and works to “catalyze a movement” to eliminate fees and inequitable fines.

Meanwhile, states began to respond. In Washington, said Nick Allen, an attorney at Seattle-based Columbia Legal Services, it was only around 2015—coinciding with the DOJ report on Ferguson—that legal advocates and lawmakers started pursuing litigation and legislation to address concerns raised for years by affected communities. Since then, the state Supreme Court has increasingly pressed lower court judges to consider a defendant’s ability to pay when imposing discretionary LFOs. And in 2018 the state legislature passed a law limiting interest accrual on non-restitution LFOs, among other reforms.

A similar story played out in other states over the next few years. Missouri reduced fees for minor traffic or municipal ordinance violations. Pennsylvania required courts to provide payment plans to those who can’t afford their fees. In North Carolina, judges committed to assessing ability to pay during hearings. Over a governor’s veto, Maine banned the suspension of licenses for non-driving offenses. The Texas legislature passed a law mandating that judges consider defendants’ ability to pay certain fines, and which made it harder to arrest people who had not paid up.

Listed like this, these developments might sound piecemeal. Nagrecha has been disappointed that after the groundswell of organizing following Ferguson, fines and fees reform became “really technocratic,” characterized, she said, by judicial rule-making and an ecosystem of nonprofits—a realm, it might seem, apart from political movements that aim to reduce the footprint of the justice system in its entirety. But while some people may see the LFO problem as an administrative one to be fixed on the basis of modernized record keeping and effective ability-to-pay tests, most observers and activists I talked to seemed to agree that, in Foster’s words, legal fines and fees amount to “racialized wealth extraction”—and that eliminating all court fees and at least a significant portion of fines (not to mention restitution) would constitute just one piece of a long-past-due overhaul of the criminal justice system.

In the right conditions, piecemeal reforms can emerge into something more comprehensive. In California, Governor Gavin Newsom just signed a bill that eliminates a vast swath of court-related fees throughout the state. California, among the earliest states to ban juvenile court debt and license suspensions for non-driving related debt, has taken more forceful action to curb legal financial obligations than any other state.

The activist groundswell began around 2015, mainly in the Bay Area, where local groups—legal clinics, for example, whose clients seemed to consistently struggle with LFO debt—filed public information requests to construct a clearer picture of the problem. These efforts led three Bay Area counties, and Los Angeles County, to eliminate a significant portion of their court-related fees. It was during this period that Debt Free Justice California—a coalition of dozens of California organizations—convened to discuss how to replicate these local victories statewide. Should they focus on fees, or fines and restitution? Advocate ability-to-pay measures or abolish the fees entirely? Ultimately, the bill Newsom signed on September 18 forbids counties from assigning twenty-three specific fees—a significant subset of sanctions whose elimination the coalition estimates will relieve more than $16 billion in outstanding debt. The bill also appropriates money for counties to make up lost revenue by drawing from the state’s general fund—itself a modest move toward the world many LFO activists desire, in which the burden of funding the justice system is one all taxpayers collectively share.

The victory in California followed a dramatic setback for those holding court-related debt in Florida. After Floridians overwhelmingly voted to grant an estimated 1.4 million ex-felons the franchise in a state Donald Trump won by only slightly more than 100,000 votes, the Republican-controlled state legislature passed a law preventing members of the cohort—an estimated 700,000 people—from voting until they paid off their legal financial obligations.

It was a jarring turn for many ex-felons who planned to vote, Marq Mitchell among them. Mitchell is now the director of Chainless Change, an organization that aids with the reentry process after prison. His LFO debt remains, but despite his best efforts, he, like many others, still does not know how much he actually owes the state (he says the number stands in the thousands of dollars). Perturbed by this legal limbo, he became a plaintiff in a lawsuit that led a district court to strike down the Republican-passed law earlier this year.

The state appealed the decision, running out the clock, preventing ex-felons with unpaid debts, like Mitchell, from voting in the August primaries. In September, an appeals court stacked with Trump appointees upheld the law as constitutional. In the days leading up to the state’s voter registration deadline on October 5, Mitchell was still making phone calls to a Kafkaesque bureaucracy in a frantic effort to figure out how to pay off his debts. Now that the deadline has passed, any hope (far-fetched though it was) for a Supreme Court intervention—or for Mike Bloomberg to swoop in and pay off the debts en masse—is now officially dead: hundreds of thousands of Florida ex-felons who hold outstanding LFOs are once again disenfranchised. Still, in defeat lies the seeds of a movement. The franchise denied to legal debtors like Mitchell only underscores the latent power they collectively hold.

Andrew Schwartz reports on labor issues and political movements. His work has appeared in the Baffler, In These Times, High Country News, and the New Republic, among other places. He also co-edits Mangoprism.com