The Bereavement of Elder Care

The Bereavement of Elder Care

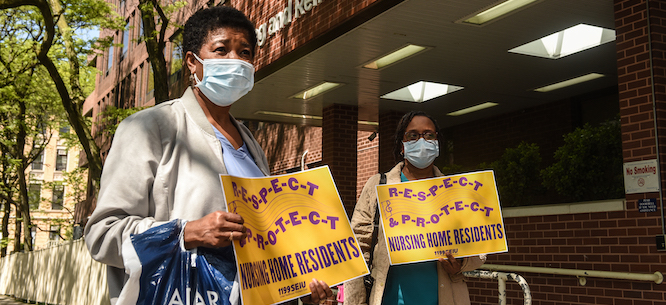

As coronavirus tore through nursing homes, workers weathered fights for adequate protection and anguish from mounting deaths.

Felicia Glasgow’s job might be easier if she loved it a bit less. As a veteran licensed practical nurse (LPN) at a Long Island nursing home, the devastation of the pandemic has left her with the kind of bereavement that can only emerge from the emotional freight of care work.

Glasgow has barely had time to grieve, though, working virtually nonstop since late March, when the outbreak began to creep through the facility, the Grand Pavilion for Rehabilitation and Nursing at Rockville Centre. (Around that time, Governor Andrew Cuomo mandated that nursing homes accept COVID-19 patients from hospitals, which likely added to New York’s horrid nursing home death toll.)

Soon, dozens of residents were infected, and the staff set up an isolated wing on the third floor to serve as an ad-hoc COVID-19 ward.

“We have had long-term residents that passed,” she recalled:

And every time you have death, it takes a little part of you. Because you work as hard as you can. When I step into that building and I get off that elevator, I go nonstop, and there are days when I don’t get out of there until 9:30 in the morning, which is two-and-a-half hours after my shift is over. Because [there] is so much to do. And I don’t think people on the outside realize how difficult it is for us. . . . [The residents] become a part of you.

The emotional burden of providing care in the last moments of a senior’s life was deepened by the isolation of the residents and staff. Like other nursing homes across the country, the pandemic forced administrators to put facilities in lockdown, forbidding family and friends from visiting.

For those who cannot fight off the virus, Glasgow continued, “when you see that you have done everything that you could possibly do, and they still die, it’s very hard. It’s extremely hard. Emotionally, it’s devastating. There were days when I would come home, and I would just sit down and cry. Because I have had residents that’ve been with me five, six years.” Many residents with underlying illnesses perished, as might be expected in such a vulnerable population. But she added that in some fortunate cases, “we thought they wouldn’t even pull through, but they did.”

The public is often not aware that “apart from being nurses, and nursing assistants, that work so hard, we are also people,” she said. “And you grow to love them, you know?”

Their work was frustrated by a medical infrastructure utterly unprepared for a global pandemic. For the first few weeks of the outbreak, the staff grappled with a massive shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE). Neither the management nor the government was able to provide the basic gear they needed for proper infection control like masks and gowns. “It was a struggle, fighting with management about proper PPE, [even though] they have to provide what we need,” she said As the staff assigned to the COVID-19 section tended to deteriorating patients around the clock—sometimes with just one nurse and nursing assistant looking after thirty-two beds—they resorted to reusing masks day after day, dousing them with disinfectant spray and saving them for their next shift.

However, as a veteran LPN and union delegate with SEIU 1199, Glasgow stepped up and made sure no one was caring for COVID-19 patients without at least basic protections, telling her coworkers to refuse to work unless they had the right gear.

“I stood up,” she said, “because, as a delegate, I have to look out for my [co-]workers, too . . . and I told them straight-up: you don’t give me PPE, we don’t go down that hall. . . . You don’t give us PPE, we are not going upstairs. I told the staff as they came in from the third floor: sit. Clock in, and sit. And that’s the kind of attitude we had to take in order to get PPEs.”

As the outbreak intensified, she recalled, she was working twelve or thirteen days straight. “There were days when they called me in on my day off,” she said, “because they couldn’t find a nurse to work my unit.” At one point, about a dozen nursing staff had fallen ill, and the part-time staff that would usually fill in were unavailable, she said, “because, if they think they’re going to send them to the third floor, they’re not going to answer [the call].”

But Glasgow was more focused on calls with the residents’ families. The staff did their best to facilitate FaceTime calls between family members using their cell phones. Over the video link, she said, “at least they can see them . . . we tried to accommodate the family as best as we could. . . . I’ve been in this field for forty-one years. And I have never, ever worked this hard. I have never been emotionally devastated as I was throughout those three months.”

In a statement, the Grand Pavilion for Rehabilitation and Nursing at Rockville Centre defended its practices, saying it had been “incredibly proactive with pre-planning our supply management before the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was announced in the United States, to ensure that our employees would have the necessary equipment to provide the highest level of care while maintaining their personal safety,” had separated patients based on whether the had tested positive or negative for COVID-19, “provided comprehensive education and training for our entire staff, and had “facilitated more than adequate levels of sufficient staffing. Our employees were never mandated to come into work on their scheduled day off.”

Now there are only a handful of COVID-19 cases left at the facility, and the chaos of the early days has yielded to a steady rhythm of infection-control protocol, with nursing staff now getting tested regularly for the coronavirus. But Glasgow worries about a second wave of infections in New York. Although her nursing home feels better prepared now, the pandemic has revealed that there are some things for which healthcare workers can never completely prepare.

When I walk in a room and a resident says, “where have you been?” he doesn’t know my name, but he knows my voice. And he says, “here comes my angel.” And then I come back the next day, and he’s not there. So I feel that this has been a great test. Not just for nursing homes, but all the frontline workers. It has been very devastating for us to lose our residents. The work is overwhelming. But every day, you keep going back.

Michelle Chen is a member of Dissent’s editorial board and co-host of its Belabored podcast.

This article was updated on July 9, 2020 with a statement from the Grand Pavilion for Rehabilitation and Nursing at Rockville Centre.