David Bowie Was Our Mirror

David Bowie Was Our Mirror

David Bowie’s lyrics were hard to mine for political content, but his songs will continue to suit moments they were never written for.

David Bowie is gone.

The sky opened up over New York on the Sunday he died with a brief but violent storm. I was on the highway and we slowed to a crawl, but by the time we reached our destination the rain was almost gone and the most spectacular double rainbow I’ve ever seen arced over the Hudson River, a rainbow that truly ranged from violet to bright red, the colors of Bowie.

This morning when I heard the news it took me a minute to connect the dots but now it feels like a sign. Bowie made things feel like magic when you didn’t believe in magic. He made the impossible feel possible.

It was “New Killer Star” from the 2003 album Reality that sent me over the edge this morning into racking sobs. It was “Blackstar” from the album he released days before the death he knew was coming, that was in my head as I climbed out of bed, having gotten the news from a text, and fed the dog and did normal morning things. The best thing about Bowie was that he changed constantly and yet you knew, always, that at the core was something beautifully strange and utterly true. In later concert performances, his old songs were changed, some utterly: the first song I put on this morning was “Five Years” from the Reality tour in the mid-2000s, a song that when it was written in the early 1970s was about the end of the world, and coming from the lips of an older man sounded like it was about the end of his life. When he knew he was dying, he turned that into more art.

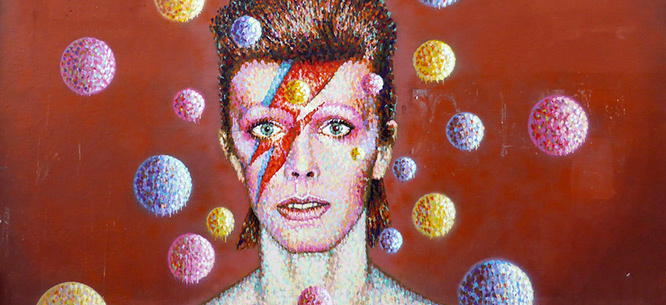

Bowie, as everyone has already said, belonged to the weird kids, the awkward ones, the queers and femmes, to everyone who’s ever felt alien. He belonged to the future, and it is so strange to think that he no longer will be part of it. He was always a little bit ahead of us.

How to sum up a life? The exhibition “David Bowie Is…” came the closest but even walking through the Bowie-approved display of his costumes, his music, his scribbled lyric sheets and musical instruments and the comic books and novels that inspired him, you would find yourself looking around for something more. He made twenty-seven studio albums, created and destroyed glam rock, played a variety of instruments, starred in children’s movies and horror films, exploded a generation’s ideas about gender, made art that evoked his working-class roots while confounding self-proclaimed intellectuals. He inspired countless others to push a little harder, to be a bit wilder.

Bowie tempts writers toward autobiography. When you write about him you write about the way he made you feel, often at a particular moment in your life when his voice was the only thing that captured what was happening to you. When I write about Bowie I remember moments of Bowie-serendipity on dance floors and in karaoke bars and in stores and out of car windows. I think of a meltdown in a cheap hotel room to the tune of “Andy Warhol,” of delicious stolen kisses, and of walking around unfamiliar cities with my chin buried in a scarf and earbuds in my ears, of fears I’d lost everything and of the possibility of something new.

To paraphrase Bowie’s contemporary (and rumored lover) Lou Reed, he was our mirror.

Bowie’s lyrics were hard to mine for political content; he famously used the “cut-up method” to rearrange the words he’d written into something stranger and more lovely. And yet his songs continue to suit moments they were never written for—“Five Years” sounds like the looming reality of climate change, “Changes,” is the epigraph for the 1980s school-rebellion movie The Breakfast Club and for my own impending book about social movements since 2008. Bowie wrote dystopia after dystopia, played with the detritus left after the world we knew was gone, and left us with so many songs that suit the moment now he is gone, too. He made us contemplate the wreckage, the inevitability of losing even ourselves, and made us stronger for it.

He was, at the end, human, though we wanted to think of him as something more. He made mistakes, did horrible things. He loved and lost and loved again. He made good art and bad art. He took risks. He changed, so many times, without having to disavow what he had been, and gave us courage to change, too. Ultimately, he was mortal, like us, and had to die, but even facing that, he was in control. He said goodbye to the people he loved, and he said goodbye to all of us, who loved him. We will all think his life was cut too short, wonder what else he could have made, since his last album is as brilliant and heartbreaking as anything he’d made.

We all have to be a little weirder, a little louder, a little more willing to change without him.

Sarah Jaffe is a fellow at the Nation Institute and an independent journalist. She is the co-host, with Michelle Chen, of Dissent’s Belabored podcast, as well as a member of Dissent’s editorial board. She is currently working on a book about social movements since the financial crisis.