“What’s Actually Going on in Our Nursing Homes”: An Interview with Shantonia Jackson

“What’s Actually Going on in Our Nursing Homes”: An Interview with Shantonia Jackson

The structural conditions shaping care work are highly exploitative—and are profoundly linked to the high degree of COVID-19’s spread within both long-term care facilities and the communities that supply their labor force.

The category that the Census calls “health care and social assistance” is the largest sector of employment in the country, accounting for about one in seven jobs nationwide. It encompasses hospitals, clinics, labs, long-term care facilities, home care, and social work agencies. This sector makes up an enormous proportion of low-wage employment growth in the United States over the past several decades: in the bottom quintile of the wage structure, according to sociologist Rachel Dwyer, a majority of new jobs since the 1980s have been care jobs of some kind. This labor market draws heavily on the most economically marginal sections of the working class. For example, the Bronx commits one quarter of its entire workforce to healthcare and social assistance, making that dispossessed borough the leader among the most populous counties in the United States on this measure.

While often overlooked, this work has drawn public attention since we deemed it “essential” with the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in the spring. The structural conditions shaping care work, however, remain highly exploitative—and are profoundly linked to the high degree of COVID-19’s spread within both long-term care facilities and the communities that supply their labor force. In nursing homes, Medicaid—the poor relation of the healthcare system—supplies the majority of all revenue, while labor accounts for the large majority of costs. This prompts nursing home operators to seek to suppress wages and staffing levels, leading to high turnover and producing negligent care and dangerous working conditions.

The growth of this workforce under such conditions has led to growing working-class organization and activity. The Bureau of Labor Statistics counts 154 work stoppages from 2010 to 2019; of these, healthcare and social assistance produced forty-five. The overwhelming majority of strikes in the last two years arose in either healthcare or education—the other pillar of the “care economy.” Alongside industrial conflict, healthcare workers have campaigned at the state level for legislative reform, including wage increases, Medicaid expansion, and tighter regulation of working conditions.

The pandemic has accelerated all of this. The hazards of the job obviously have grown far worse. Indeed, nursing home workers have been a major vector for the virus’s spread, since so many must work multiple such jobs due to low wages. Workers’ struggles have intensified with demands for hazard pay, adequate personal protection, and sufficient staffing.

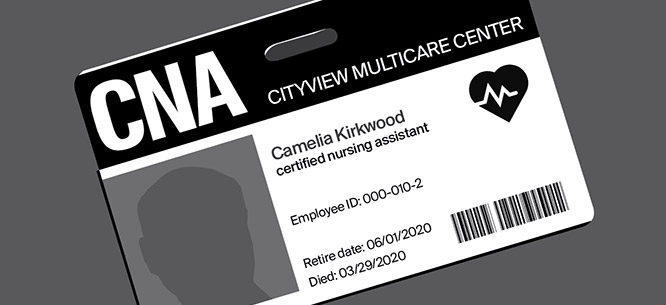

In July, I spoke with Shantonia Jackson, who is a certified nursing assistant (CNA) in Chicago. She works at City View Multicare Center in Cicero, Illinois, a union shop, and she is active in SEIU Healthcare Illinois. City View was the site of a major COVID-19 outbreak. Hundreds of residents and employees contracted the virus; many died.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Gabriel Winant: Where do you work, and what’s your job?

Shantonia Jackson: I work at City View Multicare Center in Cicero, Illinois. And I’m a CNA.

Winant: How long have you been there?

Jackson: On and off eight years, but steadily, six years.

Winant: What are the responsibilities of a CNA?

Jackson: Caring for the resident, making sure they eat, shower. And I’m their companion when they need someone to talk to.

Winant: Are the residents mainly elderly folks, or people with disabilities, or a combination?

Jackson: We’re multicare, so we have some elderly, some psych, and a lot of people are behavioral. A lot of behaviors.

Winant: Do you work in one part or another of those groups?

Jackson: No, I work with all together.

Winant: What was the job like before coronavirus started?

Jackson: Me and my coworker had thirty-five residents a piece. City View was one of the nursing homes that made the news for the outbreak. We had 253 residents that had the corona out of around 315. My coworker who worked on the unit with me passed away from the corona. Now I work with seventy men in an all-men’s unit. It’s rough, because it’s seventy brains on one brain. I’m the only CNA. It’s a lot of behaviors, but it wasn’t as bad until the corona hit, and then the behaviors got even worse. Because they were isolated and they couldn’t go out, they couldn’t leave the floors, they couldn’t leave their rooms. Some of them have schizophrenia, you’ve got a lot of ex-drug addicts. It was rough for them, and it was rough for me.

Winant: Can you walk me through a day during the virus time?

Jackson: With the PPE [personal protective equipment], you have to come in properly dressed from head to toe. It was hard for the men to social distance when they’re so used to being with each other and playing cards and playing dominos and running in and out of the building. So at first there were a lot of tantrums, and breaking things. I was one of the main CNAs, so I talked to them and explained to them, “When I leave here, I go home, and I’m on isolation also. Don’t think it’s just you guys.”

Winant: You must have known some of the residents for years.

Jackson: Yeah, because I’ve been working on that floor on and off for the last three years. Steady. But a lot of them were new and had only been there six months. A few new ones couldn’t handle it, they had nightmares; I had to coach them through it. They were ready to blow up.

Winant: How do you coach someone through it?

Jackson: When we were quarantined, we still were able to go out to the store with a mask and gloves. So, I would go to the store, get them chips, get them pops, get them things that they were used to having, but they couldn’t get. And so that would be my way of saying, “You be nice to me, and I’ll be nice to you. We’re going to get through this together. I’m sorry I’m the only one.”

My coworker who worked on the floor with me, her name was Camelia Kirkwood, she was sixty-four. She was supposed to retire on June 1. But she didn’t get a chance to retire. I was out sick with a sinus infection, before everybody was wearing masks. She had diabetes, she had high blood pressure, and I said, “Miss Kirkwood, don’t come to work.” She said, “But you’re not here, ain’t nobody gonna be here with the men, and they depend on us.” Because she had been working there over thirty years.

It just devastated me when she passed away. I really, really took that very hard. But I had to come back and explain it to the residents, because they wanted to know where she was. They were hearing that she was sick or she died, but one by one I would talk to them and let them know she was in a better place. And you have to do that with psych and behavioral patients, because they can kill you. They could take the fire extinguisher off the wall and just bash it up the side my head, you know what I’m saying? So I develop a rapport with them.

Management never came upstairs on the floor with me to see what I was dealing with. They would come upstairs and yell at me, “Well, you need to give a shower.” I already gave thirty showers out of seventy people. I can’t make sure seventy take a shower. Because I’ve got to still pass trays. I’ve got to still make beds. It’s hard.

Even with the kitchen. Even with laundry. Who wants to have bugs? It’s supposed to be clean, but the nursing home industry is so cheap. We sometimes don’t have a housekeeper on our floor. It’s like, really? Call somebody in. But you don’t want to, because you don’t want to pay them. That’s crazy.

Winant: So then they don’t have clean sheets?

Jackson: Sometimes they don’t, because there might not be anybody on laundry that day. So I’ve got to wait until the next day for somebody to come. The weekends are the worst, because on the weekends everybody wants to be at home. That’s the American dream job—Monday through Friday then you’re home on the weekends, right? But in healthcare, there’s no such thing as that. You work every other weekend. Or you work weekends because you might be a mom who has to take her kids back and forth from school and you can’t afford child care because you don’t make enough money. Then your mom is watching your kids for you at the weekend.

Winant: One thing we’ve been hearing about is how a lot of nursing home workers have to have a couple of jobs, often at different nursing homes, or maybe they do home care. And that’s one of the ways that the virus gets moved around.

Jackson: I’m glad you brought that up. I was working at Berkeley Nursing in Oak Park. And I was also working at City View. Berkeley is all seniors. I took a leave, because I felt like I didn’t want to take the virus from City View, with 253 infections, to Berkeley, which didn’t have one case. So I took it upon myself. And the nursing home industry is so fickle, and selfish, and disrespectful, because they were actually angry at me for leaving. I thought my director of nursing would be appreciative, because what if I came over here and I transmitted to all these elderly people? They all would have died. And they have the nerve to be mad at me, and calling me, saying, “You’re not going to come back?” No! I’m dealing with 253 cases over here. I want to be careful for the grandmas and the grandpas.

Winant: Can you tell me more about your involvement in the union? Was it already a union shop when you got the job? Did you unionize while you were there?

Jackson: It was already a union shop when I got the job. When I first came on the job, I didn’t believe in the union. I thought they were a bunch of crap! But as I got into it, I thought, the best thing that people could have is a union. If it wasn’t for the union, we wouldn’t have the proper PPE, we wouldn’t have anything. Because all they wanted to do was sweep it under the rug like it’s not happening. It’s happening. It’s happening. To me, they were acting like science doesn’t matter; “Oh, this is all made up.”

Winant: When did you become a shop steward?

Jackson: 2017. It’s only been a couple of years. And since then I’ve been out here saying, “Hey! Wait a minute. Hold on. Nope, nope.” I was on my director of nursing at City View. Because I had a couple of the members calling me saying, “I want to wear my mask,” and, “He won’t let me wear my mask.” And this is before the PPE was properly ordered by the governor. So, I would call him and say, “Well, you let me wear my mask.” And he said, “Because you’re the steward.” And I don’t want to hear that. So I would say, “Tell him that you’ll wear your mask or send you home. We’re always short-staffed. They’re not going to send you home.” So he would start letting some of them wear it.

He wasn’t listening. So when it hit the fan, I went right to him and said, “Huh. Didn’t I tell you? Didn’t I tell you?” He said, “Go ahead, Miss Jackson. You just think you know everything.” I said, “Hey. But didn’t I tell you?”

Winant: Can you tell me about the safe staffing campaign?

Jackson: According to the Department of Public Health, we were supposed to have 2.5 hours of care for each resident. If I have thirty residents, how could I do that? You can’t. It’s impossible. But the government gives nursing homes money if they say they don’t have enough staff. They give them extra money to hire more staff, but they steadily cut the staff. So the elderly are not getting their proper care; that’s how they get bedsores, that’s how they get dehydrated.

We wanted to let America know what’s actually going on in our nursing homes, because I think everybody was blind to the fact. Because visitors come, and they rush you out the door, and they say, “Your family’s going to be properly cared for.” And when they do the tour, they’ve got all these CNAs here—but they don’t think about the 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. shift, they don’t think about the 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift. Some of the residents don’t eat, because we don’t have enough CNAs to feed them. We work hard. We don’t even make enough money. But we care for your loved ones who nobody else is caring for. So let’s get some more staff in here.

A lot of politicians didn’t know. I had one of the senators—very hard to crack. I was at him, at him, at him, at him about what’s going on. I kept going to his office every week for about three weeks. On that third week, he said to me, “You know what? I’ve got my mom and aunt at home with me. They both have a caregiver each. And those two caregivers cannot stop them from calling me all day. And you know what? I support your bill. Because I can imagine what you go through.” And that made me feel great! Because now you understand, if they both have a caregiver each, what I go through with seventy all by myself.

Winant: If you could make nursing homes change in any way, what would be your vision?

Jackson: Oh! You don’t even want to know that. My vision would be to make sure that every CNA had at most only five residents. I would make sure it would be properly staffed. And that way we can comb their hair, brush their teeth, lotion their body, change them every two hours, make sure they get their needs, so we can do what we were put there to do, when their family members couldn’t do it. The residents would get proper food. You should see some of the food that they feed them. I wouldn’t feed that to my kid. Why would you feed them this? In America, we don’t care about the elderly; they’re about to die anyway, we don’t care. We should have respect, because they have wisdom. That’s a grandma! That’s a grandpa! And someday, you’re going to be a grandma, and you’re going to be a grandpa. And you’re going to want somebody to sit down and hear you say, “Well, my daughter never calls. She never comes and sees me.” And I could say, “But I’m your daughter! I come and see you! I love you!” To make her day special every single day, up until the day she dies.

Winant: Can you tell me a little bit about what the wages and hours and benefits are like?

Jackson: When I first started in nursing, I was making $9.20 an hour. That was eight years ago. By the time I came back, they were at $10. That was six years ago. So now, I’ve been there six years, and I make $14.30 an hour. Do you think that’s enough? To properly take care of your family members? No. It’s not. $14.30. I have a daughter in college. That’s why I have to work two jobs.

I’m not going to say this is a racist thing, but we are Black and brown. And if I’m working two jobs to make ends meet, and my son is out here getting in trouble, that’s because Mom’s never at home. If I’m working sixteen hours a day with you, I have no time to spend with my children. Just to make sure that the grandmas and the grandpas, and the mental and behavioral patients, are properly taken care of.

When I found out that the government gave $70 million for short-staffing, I thought, where’s it going? They aren’t giving it to us. Every time we bargain, you want to give me thirty cents? How do you bargain with somebody for thirty cents? And then you wonder why so many CNAs, their teeth are not right, because they can’t even afford dental insurance. They can’t even afford to buy glasses. But I’m glad that the union is there, because the union does help us with our medical insurance. It’s not the best, but it’s better than nothing.

Winant: Have you ever been on strike?

Jackson: I have petitioned to do it a few times, but no, I have never. I never had to, because I think by the time I get through with the owners . . . Every time we go bargain, I’m right there in the front. They say, “Hey, Miss Jackson, you’re breaking my heart,” and I say, “Well, you been broke mine. Look what you’re offering me. Thirty cents?”

I think that’s why, when the time came and they wanted to close City View down due to coronavirus, we really helped the owner keep his building open. Because the town of Cicero was on us. The state of Illinois was on us. They could close the building down and those employees could just walk into another job; they can get another job as a CNA. Just like the snap of your fingers. Because we come a dime a dozen. I’ve told my director of nursing quite a few times, “You ain’t gonna scare me. I am a CNA. I’m certified to clean ass all over Illinois.” It’s like the only job up in here.

Winant: I’d be curious to hear your perspective on either the local elections that have been happening here, or some of the strikes here.

Jackson: I’ve worked on three campaigns since I’ve been a leader: Governor J.B. Pritzker; Maria Hadden, where she defeated Joe Moore who represented Rogers Park for twenty-eight years; and Lakesia Collins for State Representative for the 9th District. And I feel like I’m a winner. Even when I was at Rogers Park, I had little old white ladies coming in there saying, “Ooh, Shantonia”—couldn’t pronounce my name—“she’s such a nice lady, and she breaks things down for you.” I talked to everybody. I love to talk to people. I want people to understand what life is really about. And it’s about your rights, your right to vote, your right to freedom of speech. Anything that you feel is not right, change it in your community, change it in your neighborhood, change it at your job.

Winant: Do a lot of your friends or family members work in similar kinds of jobs—CNA, home care, child care?

Jackson: Yeah. My mom was a respiratory therapist for around twenty years. And then she became a child care provider for thirty years. And all my girlfriends, they all go and take care of the elderly in their own homes. They go to the grocery store with them. I have a friend with two clients she’s had for five years. And they love her like she’s their daughter. She’s got keys to their house, she makes sure they’re safe, she makes sure they take baths, she cleans. It’s good, because I think a lot of the elderly should die at home. When they built and they bought their dream home, they should die there.

Winant: You said that 253 of your residents tested positive or had the virus at one point. What are the numbers like now?

Jackson: We only have one positive case.

Winant: Wow.

Jackson: They had to board the elevators up, so the men wouldn’t get on the elevators. They had to lock the stairs down. So just think of what I have to do to try to entertain them. I was buying my own coffee, and giving them cups of coffee, because coffee keeps them calm. “Thank you, Miss Jackson. I appreciate that.” Most schizophrenic people like to drink coffee.

I also think the pandemic was nature letting people know: they stop eating, they want to die, don’t stick them with the feeding tube. Back in the day when you stopped eating, you just died. Now you’ve suddenly got all these people in comas and feeding tubes and they can’t even speak. They can’t tell you, “Turn me.” But you want to keep them alive for the money. It’s not making any sense to me.

Winant: Because the nursing home gets reimbursed for the day?

Jackson: Right. Every day you get paid for this person staying alive. But why make them suffer?

Winant: Are there things that I haven’t asked you about, that you want to say, or that seem important?

Jackson: I think I’ve covered everything. But if there’s something else you want to ask me, please feel free—I’m not scared of people in the nursing home. When I did my AARP thing, management said, “Miss Jackson! You know the bosses want to talk to you.” And I said, “Well, tell them to call me.” They never called me. I think they thought that was going to scare me. No. Because I’ve got my union behind me; I’m allowed to do whatever I need to make my job and my members’ jobs better.

Winant: I think a lot of workers are scared for their jobs and don’t speak up.

Jackson: They don’t have to be. That’s what you pay your union dues for. One of my friends said, “I was never too keen about the union.” And when she got fired for no reason, the union got her job back. After that she called me all the time saying, “Let me know when there’s another union meeting. Because, you know, having a union is like having your own personal lawyer.” I told her, “Bing bong baby, yes, you’re right. That’s your own personal lawyer. That’s right.” As long as you didn’t do anything that wasn’t right in the union book, they’ve got to give you your job back.

Winant: But you did more than that, right? You also made the union yourself, by being an active leader in it.

Jackson: Yeah. I told them, you’ve got to come down to the meetings and see what your union is about and see what we stand for. We stand for a lot of things. We’re into politics now, which is a great thing. Lakesia Collins was a nursing home worker for ten years, and now she’s going to be a state representative. Look how powerful your union can get. I was out there talking to people about her and letting them know: this could be you someday. They said, “Oh, I’m going to vote for her!” And she won. Against Art Turner. How long had the Turners been in office? Forty years. Same thing when I was out with Maria Hadden, I would run into LGBT people and tell them, “Come on, she’s the first one that’s doing this. Let’s give her all our support, because that could be you one day.”

Something’s got to give. So that’s why I jumped on the short-staffing campaign, because I wanted people to know. And I feel like more people could stay at home if we had more home care. Instead of everybody just throwing their people off in the nursing home. You don’t have to do that. People will come out and take care of your people. The right way. A lot of CNAs drop out of being a CNA in a nursing home, and they go work as a home care provider. Because they have one patient, and they get paid $15 an hour.

Winant: Do you ever think about doing that?

Jackson: I do think about it, but I like to help the mental patients. Because nobody’s there for them. And when they think nobody’s there for them, it just makes their behavior worse.

Winant: I’ve been thinking a lot about how much money we spend on policing, compared to so many things.

Jackson: Yes! Compared to mental health. You can’t keep locking people up. Because you just make them crazier.

Winant: We’d be living in a different kind of world if there were more people doing your job, and they were paid more like cops and correctional officers are paid, right?

Jackson: I don’t have a problem with a nurse making $40 an hour. But I think I should make $20. I shouldn’t be making $10. Because when I have a doctor that calls my job, he wants to talk to the CNA, he doesn’t even have to talk to a nurse. He says, “Because you know more about him than she does. All she does is give him pills. You know about his behavior. I can ask you if you think I need to increase his medicine. You can tell me if he’s more irate, or if he’s down, or if he’s happy, or if he’s sad. Because you interact with him often.”

Winant: How do you keep track? It’s so many different people.

Jackson: I’ve got a strong mind. You just have to have a strong mind. It’s all I can do.

Gabriel Winant is assistant professor of history at the University of Chicago. His book The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America is forthcoming from Harvard University Press in 2021.

Shantonia Jackson is a certified nursing assistant. She works at City View Multicare Center in Cicero, Illinois, and is a shop steward in SEIU Healthcare Illinois.