The Pandemic Welfare State

The Pandemic Welfare State

From 2020 to 2022, Americans saw the state mobilize immense resources to boost their standard of living—and then witnessed the hard political constraints hemming in this capacity.

Over the summer and fall of 2024, public opinion polls showed that despite low unemployment, falling inflation, and robust GDP growth, a majority of Americans reported that they were worse off than they had been four years prior, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Then in November, despite the fact that the Biden administration succeeded in putting together fiscal and monetary policies that led to the U.S. economy growing faster than any of its peers in the wake of the COVID-19 crash, Trump won a large majority of the 68 percent of voters who rated the economy as not good or poor, and an even larger majority of the 47 percent who said they were better off in November 2020.

Some commentators have insisted that consumers just really hate inflation, which accounts for low ratings of the health of the economy and Trump’s renewed appeal. But consumers stubbornly refused to improve their appraisal of the economy as inflation came down in 2023. Moreover, wage growth did in fact outpace inflation for most Americans, especially lower-income Americans. And hatred of inflation had never in the past so skewed evaluations of the economy.

In the debate over this unprecedented uncoupling of consumer sentiment and statistical economic performance, COVID-19-era social provisions are often overlooked. The government put in place a slew of temporary welfare measures beginning in 2020. When those programs were allowed to lapse in 2022 and 2023, many Americans suffered an effective loss of income. Nostalgia for the economy of four years prior isn’t just real; it’s also rational.

Something exceptional happened in the United States from 2020 to 2022: not just the pandemic, but also an unprecedented experiment in welfare policy that dramatically altered the structure of American political economy to protect citizens from economic risk for the sake of their health. Americans were shown that their state can mobilize immense resources to boost their standard of living—and then witnessed the hard political constraints hemming in this capacity. The ensuing dissatisfaction with an economy that economists insist is good reflects just how popular the exceptional welfare state policies of the pandemic period were.

COVID-19 quickly proved to be highly contagious and difficult to track. Without a vaccine or effective treatment options, the disease threatened to overwhelm the American healthcare system. In response, the government coordinated a withdrawal from possible transmission sites, including workplaces. Unlike other recessions, the COVID-19 recession was chosen. The economy didn’t crash because of a panic or a slump in aggregate demand or some other endogenous economic cause, but because Americans decided to shut it down to slow the spread of a deadly disease.

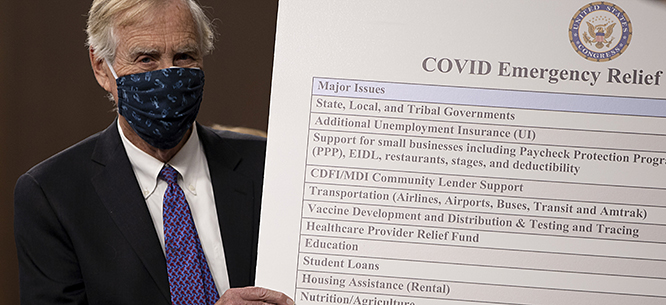

The tent pole holding up this withdrawal from the economy at the federal level was the CARES Act, which was signed into law by President Donald Trump on March 27, 2020, two days after it unanimously passed the U.S. Senate. The size and scope of the CARES Act was without precedent: at $2.2 trillion, it represented a financial commitment roughly equal to 10 percent of U.S. GDP. The CARES Act committed $300 billion in one-time cash payments of $1,200 to every American with a tax return; $260 billion to boosting states unemployment benefits; $350 billion (eventually raised to $950 billion) in forgivable loans to small businesses to fund their payroll and regular expenses; $500 billion in other loans to corporations; and $340 billion to state and local governments. It also placed a 120-day moratorium on evictions and foreclosures.

It wasn’t just the size of the CARES Act that defied precedent. It also ran counter to neoliberal nostrums. The state overrode market processes to prevent businesses (and not just those “too big to fail”) from collapsing in the face of adverse conditions. And while the U.S. welfare state has historically been relatively ungenerous, the CARES Act committed hundreds of billions of dollars to ordinary Americans.

This huge stimulus produced a paradoxical effect: even as unemployment spiked to 15 percent in April as the economy crashed, millions of Americans saw their incomes rise. Small businesses took on forgivable loans and remained solvent even as they ceased to do business. Millions more Americans began working remotely. For some, this meant working harder as their jobs’ bureaucratic demands became more complex, compounding the stressors of the pandemic. But for others, remote work meant distance from a disciplining boss and more free time. And boosted unemployment insurance gave workers in the lowest income brackets some limited freedom to quit bad jobs or refuse low wages. For millions of Americans, then, the first spring and summer of the pandemic brought not just unprecedented biomedical stress, but also a break from work not accompanied by a loss of income.

The scale of the American state’s intervention was made possible by the actions of the Federal Reserve. Under Jerome Powell, the Fed pursued a policy of quantitative easing, whereby it bought U.S. Treasury debt, cheapening the cost of the United States taking on debt by creating a market for it. It was a policy that Melinda Cooper described in her recent book Counterrevolution as “extravagance”—a phrase that evokes the new possibilities for U.S. monetary policy after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. Until 1971, the gold standard served as a kind of exogenous check on the fiscal and monetary policy of the U.S. government. However, ever since Richard Nixon ended the government’s pledge to convert dollars into gold, the United States has had the capacity to monetize its debt, as it did in the spring and summer of 2020, which in turn would vastly increase its capacity to spend its wealth on any number of public goods.

What is remarkable about U.S. domestic politics since 1971 is that this capacity has so rarely been used for the common good. Instead, as Cooper argues, for the last half-century U.S. monetary and fiscal policy have been oriented toward inflating asset prices while suppressing wages. The government pursued a policy of extravagance for those who own assets while imposing austerity on those who depend on the value of their wage for their income.

This latent possibility of extravagance for the many was made manifest in 2020. Federal Reserve policy was used to enable the U.S. government to spend trillions on a bevy of welfare policies and stimulus measures. These policies succeeded in doing two things: first, they allowed millions of Americans to become wealthier without working, and so slowed the transmission of the virus; second, they stabilized the value of assets. The U.S. stock market crashed in February and March but had recovered its value by the fall. By the end of 2020, it closed at an all-time high.

The legacy of the CARES Act and the monetary policy that made it affordable is thus, from a progressive perspective, Janus-faced. These were ad-hoc measures carried out amid a crisis by a state attempting to achieve stability, and stability meant conserving the radically unequal nature of the U.S. economy. The CARES Act bailed out businesses that continued to nickel-and-dime their workers and customers. The airlines are a case in point. They received an initial $25 billion from the CARES Act, then tens of billions of dollars more in bailouts as part of payroll protection programs. But the airlines still shrunk their workforces. When air travel began to increase as the pandemic subsided, they canceled hundreds of flights because of a worker shortage.

At the same time, the CARES Act and other pandemic-era measures (including a temporary expansion of Medicaid coverage) revealed that it was possible to extend such generosity from the state to average people. Stimulus checks—including $1,200 sent in the mail with a letter from Trump—and unemployment expansion allowed millions of Americans to become wealthier without working, and so slowed the transmission of the virus, while at the same time mitigating the power of employers to impose bad working conditions and low wages. Still, the stability of the U.S. economy was sustained not just by policy but by an immense sacrifice made by millions of Americans whose jobs were deemed essential—a category that included retail workers, healthcare professionals, agriculture and food producers, and various others. They experienced COVID-19 not as a break from their jobs, but as an intensely risky time at the workplace.

Even as the CARES Act succeeded in stabilizing Americans’ incomes and asset valuations, Trump’s response to COVID-19 was a dramatic failure. The United States failed to develop national masking and testing policies, and the disease became endemic. Half a million Americans died of the virus by February 2021. Republicans also balked at delivering more wealth to ordinary Americans. Senate Republicans refused to pass the $3 trillion HEROES Act, passed by the Democratic House, which earmarked half a trillion more for a variety of welfare measures, including unemployment benefits and another round of $1,200 stimulus checks for all Americans.

When Biden assumed office in January 2021, he was buoyed by Democratic victory in two special Georgia Senate elections earlier that month that secured the party’s control over both houses of Congress. Perhaps the most discussed issue of that race was whether Americans could expect to receive another round of no-strings-attached checks from the federal government in the next congressional omnibus spending bill. The Democratic candidates, Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, swept the election in Georgia due in part to their aggressive support for more stimulus checks. So when Biden assumed office in January, he came in with an electoral mandate for deepening America’s already ambitious experiment in welfare policies. The putsch attempt of January 6, a day after the Democratic victory in Georgia, heightened the stakes of this experiment: Trump was now an obvious and imminent threat to democratic government, and in the view of the White House, defeating him meant responding aggressively to the ongoing recession and making sure not to repeat the mistakes of the slow recovery of 2008.

Biden’s major achievements on this front were the American Rescue Plan of March 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act of August 2022. The ARP followed on the heels of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, a spending bill signed into law in late December by Trump, which included some $900 billion in COVID-19 relief money. The ARP added $1.9 trillion to this and prolonged boosted unemployment insurance, expanded access to Medicaid, expanded the child tax credit, and included a $1,400 payment to all Americans who earned less than $75,000 (this time as a direct deposit, with no letter from the president). As a result of a compromise between the Biden White House, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, and the most conservative Democratic Senators, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, many of the ARP’s most ambitious welfare provisions were temporary measures set to expire within a few months (unemployment) or at the end of the year (the expanded child tax credit). The IRA, a scaled back version of Biden’s Build Back Better Act, then brought $900 billion in government investment to emerging green energy and infrastructure projects.

From 2020 to 2022, Americans experienced a fundamentally different kind of political economy. The state insulated its citizens from some of the most acute forms of economic risk. Unemployment did not always mean a loss of income. Foreclosures and evictions were banned. Child poverty fell to its lowest rate in American history. Healthcare and food stamp subsidies were increased. All of these measures were part of a wider effort to slow the spread of a disease that was being trasmitted through workplaces. Millions of Americans learned that the state had the capacity to sustain their lives even if they did not work.

Nearly all the exceptional experiments in welfare instituted by the CARES Act, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, and the American Rescue Plan, were allowed to expire between 2021 and 2023. Foreclosures and evictions resumed and child poverty nearly tripled. Bidenomics, the name given to an experiment in ambitious Keynesianism, shifted its focus from emancipating Americans from economic risk to strategically directing state investment in geopolitical competition with China.

The American economy didn’t just return to normalcy. The recovery was stronger in the United States than nearly anywhere else in the globe: from 2022 to 2024, income inequality went down, unemployment remained low, the stock market performed well, and even an inflationary spike did not gobble up American wage growth. But Americans were telling pollsters they preferred 2020 to 2024.

Partisanship explains some of how Americans perceive the economy. But it seems impossible to understand the gap between consumer sentiment and the typical measures of economic health without reference to how exceptional the political economy of American life was from 2020 to 2022.

Rather than deepen the exceptional experiment, the Democratic Party was steered by its conservative flank to make the exceptional transient and allow the most ambitious features of the welfare state to expire. And now it is Republicans who are governing as if they have a mandate to radically reshape American political economy. Energized by a kind of right-wing utopianism, cadres of post-pubescent coders in the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) are rewiring the federal government and dramatically challenging core features of the U.S. constitutional order.

In the face of this brazen right-wing radicalism, some Democrats will be tempted to equate opposition to Trump and Musk as a return to normalcy. They may want to frame their next electoral campaigns as an opportunity to bring to a close what feels like a dreadfully exceptional crisis in American politics.

But maybe people want something radically different. During the depths of the pandemic, then New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (no one’s idea of a radical) said that the question of when to reopen the economy was a question of life, and that life was “priceless.” Cuomo’s statement appears flagrantly insincere in light of reporting that his administration hid the number of COVID-19-related deaths at nursing homes. But, taken seriously, it also shows just how radical a stance government figures took during the pandemic. This is the spirit of the former governor’s comment: the market should not be allowed to determine the worth of human life. Our political institutions exist to answer those kinds of questions and can override economic processes when we want.

We collectively chose to crash the economy rather than watch COVID-19 spread without mitigation, and then public power was used to stabilize our incomes and wealth. The extravagant policies of 2020–2022 stand as a monument to our latent capacity to subordinate the economy to another set of values, centered on our collective sense of dignity and desire to live. This horizon often seems painfully far away. But the disgust Americans have expressed about an economy that economists claimed was healthy is a resource, not an obstacle, on the journey toward that horizon.

Jordan Ecker is a lecturer in the Department of Government at Harvard University.