The Cuban Exodus

The Cuban Exodus

So long as Cubans’ rage and despair remain, the government cannot afford to curtail emigration. And there is no end in sight.

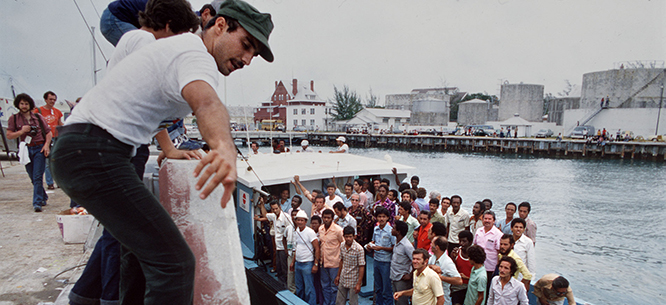

On April 1, 1980, six Cubans seeking asylum crashed a city bus through the gates of the Peruvian embassy in Havana. The Cuban embassy security detail tried to stop the van but failed, inadvertently killing one of their own in the crossfire. The Peruvian government refused to return the refugees to the Cuban government. Fidel Castro tried to strongarm them by removing the security detail, but this proved to be a grave miscalculation: thousands more raced into the embassy to claim asylum, turning what was initially a minor scandal into a major international event. After an extended siege, the Cuban government resolved the situation by allowing those unhappy with life on the island to leave via the port of Mariel. Ferried by an improvised private fleet of boats, mostly from Florida, around 125,000 Cubans left the island over the subsequent months.

We are now living through another exodus, compared to which the Mariel Boatlift is a pale shadow. Cuba’s population had stagnated for years at just north of 11 million, but over the past half decade, between one and two million have left the country as immigrants. Combined with an aging population, just north of 8 million people remain on the island (according to calculations by Cuban scholar Juan Carlos Albizu-Campos), contra the official figure of 9.7 million.

These figures are staggering for any country not in a state of war. And unlike the Mariel Boatlift, this exodus has not been met with government-organized protests to insult those leaving as “lumpen” or “worms” or “trash”; if anything, the government has encouraged them, by facilitating entry into Nicaragua without a visa, ensuring that those who have the money can get out. Emigration is now a pressure valve, letting off some of the rage and despair that exploded in mass protests in 2021, with repeated flare-ups every year since.

So long as the rage and despair remain, the government cannot afford to close the valve. And there is no end in sight. The implicit deal of the Raúl Castro era, where the Communist Party would maintain its monopoly on power in exchange for economic growth, is dead and buried, and with it the hope that things will get better anytime soon.

When I arrived in Havana in February 2024, I had a much easier time than on previous trips. I got waved through customs with minimal questions; the massive room where snaking lines of tourists and other visitors typically move over the course of an hour was empty, save for the passengers from my flight. Still, baggage claim took almost an hour, because every passenger had multiple extra bags, each stuffed to bursting. A fellow passenger, frustrated by the delay, explained the reason: “Hay hambre” (“There is hunger”). Much of the luggage was full of food and medicine. As I waited for my bags, I noticed a large advertisement for a seemingly private company that delivers various international goods, purchasable online, to addresses on the island—a departure from the state monopoly on advertising at the airport terminal. Still, as I drove from the airport down notably empty streets (a symptom of the gas shortage, with the country struggling to afford energy imports of any kind), I saw old political signs on metal billboards with slogans about the revolution. Much has changed, but some things remain the same.

My father, a Cuban migrant himself, told me when I was a child about visiting Cuba in the worst years of the post-Soviet economic collapse of the 1990s—the era labeled by Fidel as the Special Period in Times of Peace, acknowledging that the shortages were only rivaled by those during wartime. After my father and his cousin arrived, they walked a few blocks around their hotel, and then immediately came back to their rooms and slept until the next day, out of despair for how bad things were. I never fully understood that feeling until my visits in 2022 and again this past year.

The salty sea air in Havana blows in from the Caribbean, greedily eating through anything exposed to it, corroding metal as if it were acid. The city’s famous seawall, the malecón, is dotted with buildings in a state of partial or total collapse after decades of neglect, hurricanes, and periodic flooding. Moving into the city itself, there are entire houses barely kept aloft by improvised wooden supports alongside empty lots with scattered ruins, long since picked over for building materials that most Cubans cannot afford to buy from state stores. At one point, the state tried to turn the vacant lots into small parks, like the one at the intersection of 23rd Street and Paseo, but increasingly they are left as piles of rubble.

Havana feels like a city under siege. The effervescent city of the mid-2010s seems many decades away. Gone are the fresh paintjobs and the seemingly boundless expansion of small businesses following limited market reforms under Raúl Castro; some businesses survive, but they are vastly reduced. The one type of enterprise that seems to have proliferated are stores that buy food from abroad, allowed since the state compromised on its monopoly on food imports in 2020. Working-class Cubans complain that state rations of goods like powdered milk or chicken arrive late or not at all, but the corner store has all the food you could ever want.

The malecón, once a popular meeting place, feels virtually abandoned most days. And with violent crime skyrocketing, the nights have become more dangerous. I was robbed and choked out along the malecón one night in front of half a dozen witnesses, a block from the Foreign Ministry building; when I was able to identify exactly where my stolen phone had been taken in Central Havana, the police informed me it was basically a no-go zone. One Interior Ministry official mentioned in front of me that they are having staffing issues because everyone wants to leave.

Before the revolution, my grandfather was an accountant for Shell, whose office was only a few blocks from the Cuban Capitol building. When I attended college in Cuba a decade ago, much of the office building was in a state of advanced decay, despite its heavily touristed location. The structure has recently been restored to a new brilliance, but it is now filled with shops selling luxury goods that would have been hard to imagine in Fidel Castro’s Cuba: fancy perfumes, designer clothes, and lots of handbags. This capitalist Cuba had disappeared bit by bit during the 1960s, culminating in the Revolutionary Offensive of 1968, after which even small enterprises like hair salons or shoe-shine stands had to operate as government businesses. The state sector was, for all intents and purposes, the entirety of the legal economy for most of the Cold War, with the private sector only partially reemerging in the 1990s, as a result of begrudging and limited market reforms that Castro permitted in the face of the economic crisis. When I began my undergraduate studies in 2008, much of Havana “died” every evening at around 5 p.m., with a handful exceptions like restaurants (some private), gas stations, and pharmacies. By the time I left in 2013, every block of Havana had one or another small business open well into the evening, some with bright lights, blaring music, and glossy menus, in contrast with the grim, spartan, and often quite filthy state businesses. While agriculture remained largely unreformed—a major reason food is so expensive and rural productivity so low—and businesses were only allowed to be fairly small and to engage in certain activities, the reforms represented a sea change.

Staring up at my grandfather’s old office, I wondered what he would have made of Cuba’s return to capitalism so long after he had fled because of its turn to socialism. One Cuban whose opinion I didn’t have to speculate about was a working-class man I spoke with who saw his family’s car repair garage nationalized during the Revolutionary Offensive. “Listen, the revolution came and took the garage because it was for the good of the country, and we gave it up. OK. But now private property is fine again and the government recognizes that they didn’t have to nationalize everything. Are they going to pay us back?!”

Massive protests in July 2021 rocked Cuba to its core and sparked a wave of repression not seen since the early years of the revolution. Raúl Castro’s handpicked successor, Miguel Díaz-Canel, appeared on television in military fatigues, a major departure from his normal civilian dress (unlike Fidel Castro, who lived in military dress), to say that “the order for combat has been given”: “all the revolutionaries, to the streets.” In addition to images and video of security forces beating back protesters, who responded at times by pelting the police with rocks, there was evidence of deputized government supporters arming themselves with sticks and anything else they could find. In a Cuba where crackdowns had been almost surgical until 2021, the use of mass repression like this was a historic change, dwarfing even the “acts of repudiation” during Mariel. The state and its supporters saw the protests as a plot by their enemies abroad, using social media to stir up discontent. But they also acknowledged the effects of the economic crisis caused by the combination of COVID-19 shutdowns and the first Trump administration’s heavy sanctions, which the Biden administration never fully lifted. They noted how many of the protesters emerged from marginalized areas. Central Havana, the most densely populated neighborhood in the country, has a long tradition of popular unrest, most famously with the 1994 maleconazo, when thousands poured out of working-class neighborhoods onto the malecón, protesting blackouts, shortages, and the political system itself. The 2021 protests began outside of Havana and became far more widespread, eventually encompassing the whole country.

The protests included uprisings in the capital’s shanty towns (called llega y pon, after the migrants who “arrived and put” their improvised metal shacks there). These Cuban favelas include places like Marianao’s Isla del Polvo (Isle of Dust) and neighborhoods in the heart of the city like El Fanguito (the Little Muddy One). In the llega y pon, destitute populations eke out a living largely on the margins of state social programs. Many are ineligible for rations and other state subsidies because their legal places of residence lie outside the capital, making them all the more vulnerable to economic shocks. The government sought to provide more services and repair the infrastructure of these neighborhoods after 2021, but amid the current economic crisis these initiatives have largely been paused.

Under Fidel’s successors—first his brother Raúl, and now Díaz-Canel—the Cuban government made an implicit deal with the public: economic reforms would advance, giving people more viable legal avenues for surviving on the island, but only through top-down reforms. Periodic referenda allowed people to feel like they were part of the process of change, but ultimate power and authority resided in the one-party state. While at first people were skeptical of the slow and uneven economic reforms, they proved significant enough that a sizable part, if still a minority, of the total workforce was in the non-state sector for the first time in decades.

By 2021, that deal—a better economic life in exchange for a continued party-state monopoly of power—was but a memory. A flood of subsidies from Venezuela, financed by fossil fuel exports, started to dry up by the mid-2010s. Sectors like tourism helped to blunt the impact for a time, but Donald Trump’s maximum-pressure strategy soon crippled the industry. Trump’s measures included activating Title III of the Helms-Burton Act (allowing for lawsuits against those who used nationalized properties, like port facilities or hotels, on the grounds of trafficking in stolen assets) and putting Cuba back on the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism. All along, the state had retained its monopoly on imports and exports, and without revenue from tourism, it lost an essential source of foreign currency.

The fallout from Trump’s sanctions frustrated Cubans deeply, but because the government had for decades cried wolf by blaming all economic issues on the U.S. embargo, the public has laid most of the responsibility for the current crisis at the party’s doorstep. The Cuban peso’s real value has collapsed, with official exchange rates plummeting from twenty-five pesos to the dollar to 125 to the dollar, and street exchange rates falling to over 300 to the dollar—effectively annihilating any individual savings not held in foreign currency. The state has begun a process of partial dollarization in the past few months, accepting only hard currency in certain shops and for premium gasoline, in a reluctant acceptance of their inability to bring inflation down.

The shuttering of the country in the wake of COVID-19 suffocated what was left of the tourism sector overnight, while pushing the already threadbare healthcare sector to the brink. Even when I lived in Cuba in the late 2000s and early 2010s, doctors increasingly charged for services in kind (many expected “gifts,” unless you had connections) to compensate for largely symbolic salaries, and sanitary conditions at hospitals were deteriorating quickly. One man I knew from friends went to the doctor for a small medical issue but died from hepatitis C due to an improperly sterilized needle. The state’s increasingly chronic incapacity to produce or import sufficient medicine, even basics like Tylenol, has forced people to reach out to friends and family abroad for medications, without which they would face disability or even death.

Despite initial success containing COVID-19, in the early months of 2021 the virus broke out unchecked, spreading quickly among the island’s still unvaccinated population. Between mounting economic frustrations, a collapsing healthcare system, and massive blackouts due to fuel shortages, all combined with summer heat, it was no wonder that by July 2021 people had had enough.

There is currently no solution on offer to address the breakdown of the implicit deal between the Cuban government and its people. The more confident slogans of the past, like Venceremos (We Will Triumph) or Patria o Muerte (Fatherland or Death), have increasingly been replaced by the more modest Mejor es possible: better is possible. Fewer and fewer people seem to believe it. When I asked various Cubans about the future, some expressed their frustrations with a frankness surprising in a police state. They consistently replied that they felt powerless and admitted that “tenemos miedo” (“we are afraid”). Given that police responses to protests during and after 2021 have involved extended prison sentences and at times the mobilization of the black berets—a special forces branch within the Ministry of the Interior—this fear is not hard to understand. As in the classic framework of German economist Albert O. Hirschman, with the options of “voice” (protest) and “loyalty” to the regime exhausted, more Cubans are turning to the remaining choice: exit.

In the three years leading up to September 2024, around 850,000 Cubans arrived in the United States. During the past half decade, the trio of Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua have at times even overtaken the historic sources of most Latin American immigration to the United States, including Mexico. After the 2021 protests, the Cuban government brokered a deal with the dictatorship of Daniel Ortega, allowing Cubans to travel to Nicaragua without a visa (Havana had already abolished its Soviet-style “exit visa” years ago).

While many of these emigrants eventually come to the United States, some are starting their lives over elsewhere in Latin America or in the booming Cuban community in Spain. Some have even made international headlines by joining the Russians in their invasion of Ukraine, in exchange for citizenship. One older Cuban man I met on a flight from Havana to Colombia told me he was traveling to Bogotá in order to take a flight from there to Nicaragua, because all the direct flights to Managua were booked up. When I asked the man, who had the deeply tanned appearance of a farmer, if that meant that he planned to go on foot from Nicaragua to the United States, he said yes, and then just stared ahead, lost in thought.

It isn’t only poorer Cubans who are leaving. Government ministries are facing recruitment issues: a judge named Melody González Pedraza, who had sentenced protesters to jail time after the 2021 demonstrations, arrived in the United States last year and applied for asylum. In October 2024, Cuba was abuzz with the news that a government vice minister, Juan Carlos Santana Novoa, had made his way to the United States to apply for asylum while on an official trip to Mexico; he seemingly reached the United States while still vested with his official title and powers. Although it is hardly new for disaffected Cubans to leave the island for various reasons, even after long careers in government service, the sheer scale of former state figures now fleeing the country or retiring to South Florida has not been seen since at least the Special Period of the 1990s.

What happens next is hard to predict. Popular support for the government appears to be at an all-time low, with the caveat that Cuba doesn’t have publicly available polling data. But so long as the police, military, and others in the government do not fracture in the face of protest, their grip on power will remain secure. Economic conditions seem unlikely to improve anytime soon, which means that the government would be unwise to try to limit the exodus that is depopulating the island. Yet how many people can a country lose—especially young, healthy, and educated workers—before things start to fall apart?

While aggressive market reforms in the countryside years ago might have spurred the kind of economic booms seen in China and Vietnam in the 1980s, rural Cuba is now increasingly uninhabited, full of near–ghost towns whose only residents are elderly and decapitalized to the point of lacking even draft animals. Foreign aid from Russia, China, Mexico, and Venezuela has helped to save the country from complete collapse, but none of Cuba’s supporters are ready to offer the massive subsidies needed to get the economy back on its feet. And even with more money, the country’s crumbling energy infrastructure, which causes chronic blackouts, would take years to replace. In the meantime, it is hard to run an economy without power.

The nationalist messaging on which the government has relied for decades is also losing its effect. By late in the Cold War, Cuba, like its Eastern European allies, had jettisoned the idea of overtaking the capitalist world, but the idea of a proud, morally superior, and sovereign nationalist state at least helped to numb the economic pain. Today the country’s once-lauded education and healthcare systems are not just threadbare but increasingly nonfunctional, and the emigration of so many Cubans is a national embarrassment.

A decade ago, talking too loudly against the government in public could get you in trouble; today, standing in lines for rationed and increasingly expensive goods, you might hear people shout down those who try to defend the government. While the threat of repression has deterred a resurgence of mass protest, such public criticism speaks to the extent of popular discontent. The new low in national pride is especially clear among the youth. One Cuban academic has gone so far as to openly state on Cuban television that his university students see being born in Cuba as the greatest misfortune that could have befallen them. The social justice programs and economic modernization promised by the revolution lie in ruins, leaving the island increasingly populated by those too old, too poor, or too sick to leave, and the ghosts of a dream that has long since become a nightmare.

Cubans may not be able to vote for change on the island, but they can vote with their feet. On that front, it’s a landslide.

Andrés Pertierra is a PhD candidate in Latin American and Caribbean history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, specializing in Cuban history. He has been invited to share his expertise on media such as the BBC and Deutsche Welle.