The Austerity Politics of White Supremacy

The Austerity Politics of White Supremacy

Since the end of the Confederacy, the cult of the “taxpayer” has provided a socially acceptable veneer for racist attacks on democracy.

From the Southern strategy of the 1960s to Donald Trump’s refusal to concede the presidential election, it is easy to trace the Republican Party’s decades-long descent into racial authoritarianism. Despite the president’s unhinged response to the election results, the real locus of power is the Senate, where Republican legislators have been striking sober-sounding notes about the need for smaller government, an end to relief spending, and the danger of higher taxes. Those desperate to see a return to normalcy may hail this born-again fiscal conservatism as a departure from Trump’s racist, antidemocratic politics. Historically speaking, this is a false distinction.

Long before Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan, the dog-whistle rhetoric of austerity provided a socially acceptable veneer for racism. And long before the Trumpist GOP, the agenda of the American right was undermining democracy and passing tax cuts for the rich. When the former Confederate elite mobilized to successfully overthrow the multiracial Reconstruction-era governments in the South 150 years ago, it was under the banner of fiscal conservatism.

In the South after the Civil War, under the protection of federal troops and a radical Republican Congress, black legislators in coalition with white allies from the North and from the South’s poorer regions set to work rebuilding their states’ infrastructure and constructing a public school system. Reconstruction-era economic policies were relatively moderate, eschewing land reform, but included new forays in social spending in support of the poor and sick, as well as efforts to increase the taxes paid by landowners.

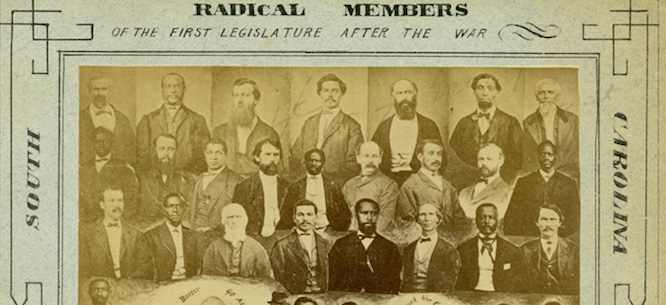

Across the South, the planter class engaged in massive resistance to the new state governments. The campaign came to be known as the “Redemption” of the South, and its participants as “Redeemers.” In South Carolina, democratic rule posed a particularly big obstacle to the opponents of Reconstruction; the majority of the state was black, and under universal male suffrage, a majority of the state legislature was black, too.

South Carolina’s white elite developed a two-part strategy of opposition. First, they focused their critique of Reconstruction on rising government debt and excessive spending, painting government by black people and poor whites as intrinsically corrupt. Adopting a new identity as concerned taxpayers helped the rich bridge the divide with small white farmers, for whom new land taxes were heavy, while avoiding explicit opposition to black male suffrage, which might smack of treason to Northerners.

While the opponents of Reconstruction were painting themselves as staid and respectable fiscal conservatives, they were simultaneously engaged in a radical plan to subvert democratic elections across the South. In principle, the Redeemers’ open campaign of voter suppression, political intimidation, and violence risked further federal intervention, but the North was losing the will to defend black political freedom. In fact, wealthy Northerners—even those who had been strongly anti-slavery—began doubting the logic of universal male suffrage as it empowered the immigrant working class in their cities. The political identity of the “taxpayer” was born in this reaction to black freedom and working-class political power, and it has existed ever since to oppose the specter of a multiracial working-class alliance.

Called together by the Charleston Chamber of Commerce and the Charleston Board of Trade, the Tax-Payers’ Convention of South Carolina met in Columbia in May 1871 and again in February 1874 to seek, “for the holders of property and the payers of taxes, a voice and a representation in the councils of that State.” They had a duty to speak up, the Tax-Payers argued, because the state of South Carolina was suffering from “the fearful and unnecessary increase of the public debt”; “wild, reckless and profligate” spending; and “excessive taxation.”

Until recently, most of these “holders of property” had owned rather a lot more property, in the form of human beings. Surrounded by former governors, senators, bankers, and other elites of the Old South, convention president W.D. Porter welcomed the “old familiar faces” he had known as a member of the South Carolina legislature before the Civil War.

Even by South Carolina standards, the leading Tax-Payers were among the most ardent defenders of slavery and the most unreconstructed of Confederates. Most active in the convention’s proceedings were former Confederate General James Chesnut Jr., one of the figures who had in 1861 ordered the firing on Fort Sumter; former Confederate General Matthew C. Butler, first cousin to Preston Brooks, who had beaten Charles Sumner nearly to death on the Senate floor; and former Confederate General Martin W. Gary, who had literally refused to surrender at Appomattox.

Though the proceedings are interspersed with laments for the “elegant hospitality” afforded by chattel slavery, the Tax-Payers took pains to note that they accepted defeat in war and emancipation as “finalities” and “dead issues.” Most remarkably, however, the Tax-Payers also insisted that they were not motivated by racism. In his 1874 opening address, convention president Porter claimed that the problem with South Carolina’s Reconstruction government was not a matter of “race, or color,” but “simply and exclusively” that the government was run by those who did not own property.

Emphatic color-blindness was, to say the least, a recent development in the public rhetoric of South Carolina’s white elite. As recently as 1868, a number of Tax-Payers had signed a petition to the U.S. Congress, entitled a “Respectful Remonstrance on Behalf of the White People of South Carolina,” that opposed black male suffrage because “the superior race is to be made subservient to the inferior.” Porter himself had argued that black people had “traits, intellectual and moral,” and “credulous natures” that left them with an “incapacity” to rule.

At their Tax-Payers’ Conventions, however, these same men, despite sporadic remarks on the “negro character,” no longer officially identified themselves as advocates on behalf of the white race; they were simply representatives of the “over-burthened tax-payers.” This self-appointed role was ironic: as slaveholders, the Southern elite had done everything in their power to cripple the tax capacity of both their states and the federal government. Now, the South Carolina Tax-Payers called into question the right of black people and poor whites to govern because they believed these voters did not pay a substantial amount of taxes. “They who lay the taxes do not pay them, and that they who are to pay them have no voice in the laying of them,” Porter asserted, wondering if “a greater wrong or greater tyranny in republican government” could be conceived.

As W.E.B. Du Bois would later explain in Black Reconstruction in America, the “fact that poor men were ruling and taxing rich men” was the “center of the corruption charge” made by wealthy Southern whites against the Reconstruction governments. The Tax-Payers deemed all government spending under Reconstruction suspect, so they did not feel obliged to engage in subtle, or even plausible, analyses of public finance. For instance, the Tax-Payers consistently compared pre- and postwar expenses, ignoring the fact that emancipation had doubled the state’s citizen population while war had decimated its infrastructure and economy. There was no need to specify what particular spending was objectionable—which was convenient, because a number of the Tax-Payers were themselves involved in rather shady dealings involving railroads and government bonds.

The fundamental problem for the Tax-Payers was their numerical inferiority in a system of majority rule. They estimated that South Carolina had 60,000 taxpayers, and “90,000 voters who pay no taxes.” They considered, halfheartedly, two plans to improve their prospects within the confines of a democratic system: a proportional voting system they referred to as “cumulative voting,” and encouraging white immigration to the state. But such plans were inadequate. General Matthew W. Gary, chair of the committee on elections and suffrage, said he would accept cumulative voting “in the same spirit that I would receive a half loaf as being better than no bread at all.” “We, by this cumulative voting, shall be confined to one-third the power to which we are entitled,” complained former Governor John L. Manning.

They settled on another solution: bring poorer whites to their side, intimidate black voters, and reclaim power in the state by any means necessary—all without provoking the ire of Northerners, whose commitment to federal troops in the South was an essential protection for black voters. Taking up the mantle of the taxpayer aided the convention in all three endeavors.

Early in Reconstruction, Democrats across the South had been astonished to find that straightforward appeals to racism had not produced consistently favorable electoral outcomes. A troubling number of whites in the hilly, poorer “upcountry” were willing to vote with the freedmen in the Republican Party. “Let no foolish prejudice stand in the way” of an alliance against the “rebels,” argued one Republican newspaper in North Carolina.

Taxes offered a different electoral entry point for the aristocracy of the Old South. Reconstruction governments desperately needed revenue for infrastructure and schools, and the resulting tax increases hit small farmers hard. By focusing on their identity as “taxpayers,” planters could elide the vast economic gulf between themselves and subsistence farmers in Appalachia.

Accordingly, the South Carolina Tax-Payers called for the organization of “tax unions.” On the surface, these organizations were intended to track local government revenue and spending, but the Tax-Payers hinted at their true purpose when they suggested that the unions would be able to exact “just punishment” on government officials. Taxpayer leagues across the former Confederacy began a concerted campaign of tax resistance. In close coordination with openly violent white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, they threatened, attacked, and sometimes killed government representatives, especially when those officials were black. The strategy worked to bring poorer whites into the Democratic fold. When its members began intimidating and murdering revenue agents responsible for imposing a much-hated tax on liquor, the Klan found a toehold in white areas that had previously shown Republican strength.

The line between tax resistance and paramilitary antidemocratic violence was vanishingly thin. In the Vicksburg Massacre in Mississippi in 1874, the local taxpayer league marched to the courthouse on Tax Day and demanded that all black officeholders resign, including the sheriff responsible for collecting taxes. After a standoff that lasted over a week, they opened fire on the black militia, killing between 75 and 300 people. “Those that fell wounded were murdered,” reported Blanche Ames, the governor’s wife. And still, the respectability of the “taxpayer” provided protection; in a hearing investigating the massacre, one member of the local taxpayer league insisted that “there was nothing political in it; colored men, if tax payers, could join.”

The Vicksburg Massacre was no anomaly. Economist Trevon Logan finds that public finance was directly related to the strength of the violent reaction to Reconstruction. The chances of a local black politician being attacked increased three percentage points “for each additional dollar of per capita tax revenue collected in 1870.” Where taxes had increased more, the violence against black politicians was higher.

South Carolina was, as usual, the most extreme case. While Chesnut, chair of the South Carolina Tax-Payers’ executive committee, was assuring a congressional committee investigating Klan attacks that violence was “local and limited” and not “political” in nature, Gary, the leader of the South Carolina Tax-Payers’ committee on elections, was personally plotting the violent overthrow of local democracy.

Remarkably, Gary’s original draft of his “Plan of the Campaign 1876,” which was edited and sent to Democratic county leaders across South Carolina, has been preserved. “Democratic Military Clubs are to be armed with rifles and pistols,” he wrote. “Every Democrat must feel honor bound to control the vote of at least one Negro, by intimidation, purchase, keeping him away or as each individual may determine, how he may best accomplish it.” Gary’s original plan told Democrats to “Never threaten a man individually if he deserves to be threatened, the necessities of the times require that he should die.” This campaign was part of a wave of violence and intimidation that swept white supremacists back to power; it would be nearly a century before black men in South Carolina would again be able to exercise their right to vote.

Just over a decade after the Civil War had ended, Northerners might be expected to balk at a Confederate general who had refused to surrender at Appomattox organizing paramilitary forces to seize power in South Carolina. Instead, Northern elites were a highly receptive audience for plans to empower the “taxpayers” against rule by the corrupt and incompetent poor.

In July 1871, the Nation, like many other Northern media outlets, covered the proceedings of the Tax-Payers’ Convention of South Carolina. Though the magazine was founded by abolitionists, the article’s tone was sympathetic. “The Convention was a most respectable body and represented almost the whole of the taxpaying portion of the population”—the very people who “it is conceded on all hands . . . must eventually purify Southern politics, if they can be purified.” The friendly coverage stemmed in large part from a feeling of shared struggle. The convention’s report of corruption in South Carolina mirrored those “financial exhibits which municipal reformers occasionally lay before the public in [New York City].”

In its report, the Nation gestured toward the defense of universal male suffrage; the Tax-Payers “will have the hearty sympathy of the best Northerners” only “as long as they show a determination to accept the fact that the people of the South now means the whole population of it.” But this caveat must have rung hollow even at the time. Just two months after their positive review of the convention, the Nation considered the “vast horde” of immigrants coming to New York and concluded that democratic city government was a “ridiculous anachronism.”

The Nation was giving voice to an increasingly popular opinion among the Northern economic elite. Spurred by fear of the Paris Commune, the flood of European immigrants bringing class consciousness to American cities, and the growing organization of labor, wealthy Northerners came to see themselves as a victimized minority under attack. By the late 1870s, an “anti-corruption” commission of New York business leaders organized by Democratic Governor Samuel Tilden would publicly demand that “the excesses of democracy be corrected” by the passage of an amendment to the state constitution bringing an end to universal male suffrage. The amendment would have put all decisions concerning municipal taxation, spending, and debt in the hands of a “Board of Finance,” elected by those who paid at least $500 in annual property taxes, or a yearly rent of at least $250 (approximately half the salary of a skilled worker). The proposal would have disenfranchised between one- and two-thirds of the voting public.

After initially lobbying to limit suffrage even further by excluding rent-payers from the electorate, the recently founded New York Taxpayers’ Association organized in support of the amendment. Their meetings were, as the New York Times put it, “a notable demonstration of the solid wealth and respectability of the Metropolis.”

It takes a certain audacity to argue that men of property were the proper custodians of government just as the term “robber baron” was entering the national lexicon, but the anti-tax, antidemocratic attitudes in New York’s business leaders were shared by elites in other major cities. Francis Parkman, the prominent Boston historian, wrote an article in 1878 entitled “The Failure of Universal Suffrage.” In cities, the “dangerous” effect of “flinging the suffrage to the mob,” Parkman argued, was that the “industrious are taxed to feed the idle.” Rather than civic institutions beholden to the public, Parkman reimagined cities as business entities: “great municipal corporations, the property of those who hold in stock in them.” Working-class men in New York City managed to protect their suffrage rights against the taxpayer-citizen amendment, but new tax standards for suffrage passed in towns in upstate New York, Maryland, Vermont, and Kentucky, and were seriously considered by several Northern state legislatures.

It was in this context that the North abandoned its commitment to black freedom. To end a stalemate brought about by an unclear count in the Electoral College, the Republican Party traded their defense of black voting rights for continued control of the presidency. Federal troops were removed from the Southern states, and Rutherford B. Hayes became the nineteenth president. America’s first brief experiment with multiracial democracy was over, and it would not be tried again for one hundred years.

After the Reconstruction governments fell, a new fiscal state served to reinforce white supremacy and strengthen antidemocratic institutions. Under the guise of protecting the taxpayer, the white supremacist Redeemer governments slashed public budgets and shifted taxes onto the poor. Oppressive fees and fines forced black people into a new slavery of convict leases and chain gangs. Eventually, new state constitutions included poll taxes to reinforce black disenfranchisement, and tax limitations that required supermajorities to overturn, ensuring that wealthy whites could shield themselves even if most citizens wanted to raise taxes.

It is no coincidence that when the Jim Crow laws were finally dismantled, the reaction to the civil rights movement once again featured paeans to “the taxpayer” and a new wave of tax limitations. The rhetoric of the taxpayer is readymade to call into question the right of black and poor Americans to participate in or benefit from their government. The taxpayer was the foil to Reagan’s welfare queen, who he claimed had a “tax-free cash income” of $150,000 a year. Reagan’s story was a fiction—he’d change the numbers from speech to speech—but that hardly mattered. Talking about taxes allowed voters to put a dollar figure on their resentments, and to experience the poverty of others as persecution.

Over thirty years later, GOP presidential candidates were still singing the same tune. Mitt Romney interpreted federal income tax data as evidence that 47 percent of Americans “are dependent upon government” and “believe that they are victims.” The state, local, and payroll taxes that fall heavily on lower-income people did not, for Romney, qualify as contributions to government. “My job is not to worry about those people,” Romney continued. “I’ll never convince them that they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives.”

Romney was widely criticized for his comments in the mainstream press, but his views were not out of line with his party. A survey in 2014 found that half of all Republicans agree that only taxpayers should have the right to vote. An electoral map circulated through social media that claimed to show a landslide victory for Romney, if “only taxpayers voted.” Tellingly, the doctored map was actually based on the Electoral College result if suffrage were limited to white people. The reality of taxpaying never had much to do with who was meant by “taxpayer”—a point driven home by President Trump’s popularity with the Republican base even as he celebrated his own tax avoidance.

Given how long racial oligarchy has found a friend in fiscal conservatism, the strategy of the contemporary GOP seems highly unlikely to change. Only repeated electoral defeat massive enough to overcome our inertial and minoritarian institutions would change the incentives of the party. Instead, we should expect to see a low-key variation on the Redeemers’ politics: continued subversion of the institutions of representative democracy accompanied by calls for tax cuts, deregulation, and austerity.

What is perhaps most troubling is that the rhetoric of the taxpayer will likely continue to provide antidemocratic reactionaries with allies in much the way it did at the end of Reconstruction. Fiscal conservative rhetoric appeals to the wealthy in liberal enclaves. Across parties, rich people are markedly more economically conservative than other Americans, and they tend to get what they want from policymakers. In preparation for a Biden White House, Republican legislators have already readopted the austerity-by-gridlock posture they held under the Obama and Clinton administrations, and Democrats do not seem prepared to make a fight of it. There are already deficit-hawk rumblings from the Biden administration.

We have had 150 years of the dog-whistle politics of the taxpayer. If the Democratic Party is to be the party of racial justice, it cannot also be the party of austerity.

Vanessa Williamson is a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution.