Sins of Omission

Sins of Omission

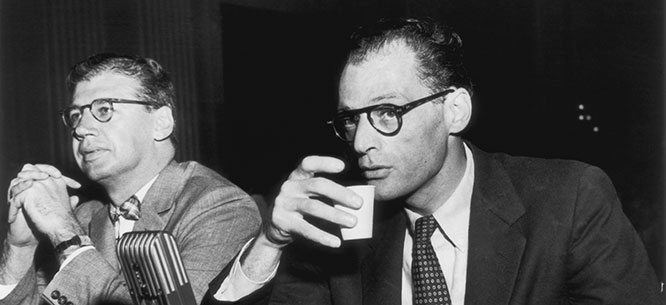

Arthur Miller’s landmark play The Crucible illuminates the difference between informing and truth-telling.

John Proctor Jr., a Puritan settler of Salem Village, Massachusetts Bay Colony, was convicted of witchcraft in a Salem court on August 5, 1692, and hanged two weeks later. He was one of twenty men and women executed in the Salem witchcraft trials.

Roughly two and a half centuries later, a character named for and loosely based on Proctor appeared as the protagonist of Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, which opened on Broadway on January 22, 1953. As New York Times drama critic Brooks Atkinson noted in a dry understatement in his review of the play, “Neither Mr. Miller nor his audiences are unaware of certain similarities between the perversions of justice then and today.”

The Crucible would become Miller’s most frequently performed work. But its reception in 1953 was mixed, although it won a Tony Award for Best New Play of 1953.

A week after his initial review, Atkinson devoted a column in the Times to some second thoughts on the parallels implied in The Crucible between the “perversions of justice” in seventeenth-century Salem and mid-twentieth-century America. While there “never were any witches,” Atkinson now felt compelled to point out, “there have been spies and traitors in recent days. All the Salem witches were victims of public fear. Beginning with [Alger] Hiss, some of the people accused of treason and disloyalty today have been guilty.”

Atkinson had been an outspoken critic of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) and Senator Joseph McCarthy. That he felt obliged, in effect, to review Miller’s play a second time, and more critically than the first, is revealing of the political pressures and complexities of American anticommunism in the McCarthy era. American Communists were being victimized in those years in ways that, like the Salem trials, and more recently the Red Scare of 1919–20, represented a cruel miscarriage of justice. At the same time, Communists were not without their own sins. Charges of “espionage” in the 1940s and 1950s were not always instances of malicious hyperbole.

The “McCarthy era” of American politics, known for the hurling of reckless partisan accusations of Communist subversion, is somewhat misnamed, since the junior U.S. Senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, only became associated with the issue when he charged, in a highly publicized speech to a Republican gathering in February 1950, that scores of U.S. State Department personnel were card-carrying members of the Communist Party. By then, the post–Second World War Red Scare was nearing the half-decade mark. It was an era of mass hysteria and official repression that wrecked lives and careers and tarnished American democratic ideals in the name of defending them. It also would outlive its namesake, who died in 1957.

On June 19, 1953, the night that convicted atomic spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg died in the electric chai...

Subscribe now to read the full article

Online OnlyFor just $19.95 a year, get access to new issues and decades' worth of archives on our site.

|

Print + OnlineFor $35 a year, get new issues delivered to your door and access to our full online archives.

|