Native Americas

Native Americas

We tend to take the present-day shape and status of the United States as a given. What if, instead, we envisioned the Americas as a region of overlapping indigenous territories?

Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power

by Pekka Hämäläinen

Yale University Press, 2019, 530 pp.

At my elementary school in Baltimore in the 1990s, we celebrated Thanksgiving in style, with feathered headdresses made of construction paper and stories about Squanto, who taught the Pilgrims to farm. Later, we learned that Native American women made history too: Sacagawea helped Lewis and Clark explore the Louisiana Purchase, while Pocahontas saved John Smith. I can still remember the mournful lyrics of that pseudo-environmentalist ballad from Disney’s Pocahontas: “Can you sing with all the voices of the mountain? Can you paint with all the colors of the wind?” The implicit lesson was that we could not. Popular culture trained us to view Native Americans and their presumed unusual talents as relics of the past.

In 1992, my class observed the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage to the Americas by reciting a poem about the Genoese admiral’s sense of adventure, even as the broader political winds began to shift. Indigenous activists were organizing new social movements from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, and historians were revising their approaches. The symbolic anniversary helped critical voices to resonate. Rigoberta Menchú Tum of Guatemala won the Nobel Peace Prize, the United Nations proclaimed an International Decade of Indigenous People, and the Zapatistas declared autonomy in southern Mexico. As conversations about the legacies of settler colonialism, dispossession, and genocide became more common, some U.S. cities, counties, and states decided to observe Indigenous People’s Day in place of Columbus Day. This spirit of reckoning has affected even our most cherished civic rituals. Mommy bloggers now advise readers to “say no” to Pocahontas costumes on Halloween, while progressive journalists warn that “everything you learned about Thanksgiving is wrong.”

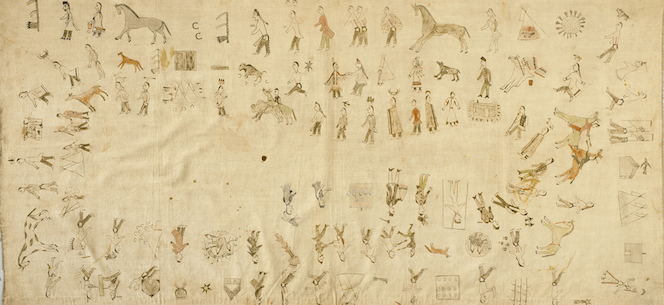

Still, most contemporary discussions about indigenous history in the United States operate within the same problematic framework that my elementary school curriculum did. Whether celebrating Native Americans’ contributions to the republic or lamenting colonial violence, we tend to take the nation’s present-day shape and status as a given. What if, instead, we envision the Americas as a region of overlapping indigenous territories? For more than five centuries, European empires and then American nation-states have tried to conquer those lands. Many indigenous people lost their lives to colonial violence or epidemic disease, but Native Americans also survived, adapted, and continued to make history. The legacy of conquest is something that Americans across the hemisphere share. How we understand that legacy affects how we imagine the future.