Moral Limits

Moral Limits

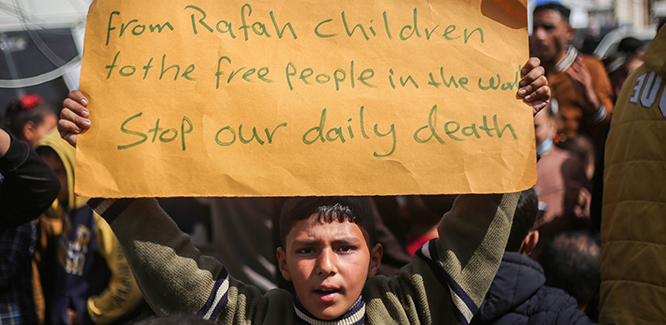

Our empathy seems to make us righteous—even as we benefit from an unequal world.

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This

by Omar El Akkad

Knopf, 2025, 208 pp.

What is the point of our moral ideals in a world where people can endlessly express care and concern for others—those living in zones of everyday poverty or spaces of terror like Gaza and Tigray—but do nothing in practice?

This question haunts Omar El Akkad’s new book, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, a powerful account of our failures to stop the war in Gaza. What makes El Akkad’s book especially striking is the doubts he comes to harbor about his own profession, writing, and how it shapes our moral convictions. When Kamala Harris can stand at the Democratic National Convention one night and say she wants to end the war and then send bombs to continue it the next morning, is there any logic left to making moral arguments? In El Akkad’s painful refrain: “What is this work we do? What are we good for?”

El Akkad takes us up to the point of utter resignation before ultimately reasserting the value of this work. The journey itself, the willingness to tarry with this nihilistic possibility, is what gives this book its strength. He does not leave us in hell but insists that we recognize we are already in one.

For many of us outside the halls of power, writing remains one of the most visible means of fighting back. Even as El Akkad doubts its utility, he still writes a book that he hopes might eventually change how people treat one another—both morally and materially. He scrapes language, stories, and every element of his imagination to find some way of writing and speaking that might finally push the powerful from vague invocation to concrete action. His book is urgent as much for its potential success as for its insistence that we grapple with the painful limitations of the world of ideas and values to which many of us have dedicated our lives.

El Akkad is not the first person to wrestle with the relation between writing and effective moral change. As far back as Aristotle, philosophers have wondered if the written word could meaningfully shift how people felt and acted. Aristotle himself suggested that tragic plays could help us empathize with other time periods, but our empathy, or pity, would always stop at those who resemble us in “age, character, habits, position, or family.”

El Akkad’s family fled Egypt for Qatar when he was a child and then moved to Canada when he was a teenager. In the book, he describes his excitement at finally moving to a place where Aristotle’s limitation seemed to have been transcended. In his youthful vision, Canada, and the West more broadly, had created a world order in which the ultimate mission was not only the safety and security of its own citizens, but the well-being of all humans—even if the global society of nations had not yet succeeded in that aim.

Particularly dear to El Akkad’s development in the West was the freedom to read and write. Even as the minor slights of Canadian youth grated on him—like mispronouncing his name or asking him if everyone went around by camel where he was from—the promise of the written word elevated him. The first time he took a book out from the library, it was William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, on the recommendation of an overly confident college student at a party. More than the book itself, what appealed to his teenage self was the mere fact that he could ask the librarian where to find it and they didn’t even bat an eye. “I remember thinking,” he writes, “if this is all there is, it’s enough,” because the freedom to read promises a culture committed to “its own rights and freedoms and principles.” He chose a career as a journalist and later went on to write two novels: American War (2017) and What Strange Paradise (2021).

It is perhaps not surprising that literature and the ability to read literature is fundamental to El Akkad’s story of being enchanted by the West. According to Lynn Hunt, in her history of the origins of human rights, novels recreate rich interior lives that help people learn to empathize with one another. They were the motor behind the universal moral concern and liberty that El Akkad once associated with the West.

Moral philosophers like Adam Smith also advocated for this universal morality through fictive thought experiments. For example, he asked readers to imagine how they would feel if all of China were to be suddenly destroyed in an earthquake. They might, Smith says, feel sorrow for the immense loss, reflect on the tragic nature of human life, and consider the political and economic fallout. And then they would, in all likelihood, move on with their day. But imagine instead losing a little finger, he writes. It would become their consuming concern. They would think of almost nothing else for days and perhaps lament their fate for years to come. What was for Aristotle a natural proclivity becomes for Smith a moral failure. We may care more about our little finger than all of China, but we are wrong to do so.

The moral is in theory good, but the devil is in the geographical details. The split in decency that El Akkad witnesses in the present already existed in the Enlightenment. For while Smith and others professed that Europeans should extend their concerns to the Chinese, they didn’t always believe that the Chinese could do this for Europeans. Europe’s supposed moral advance thus created a globe-sized problem: expanding morality gave it a civilizing mission. Although colonization and enslavement were said to be morally wrong and only temporary, they were also said to be historically justified and even necessary as part of the path to becoming moral like Europeans. For everyone to have European morality, Europe must first violate that very morality through violent colonization.

When the college student first recommends Naked Lunch, he does so because it contains the story of a man being consumed by his own asshole. El Akkad tells us that the student asked him if he understood the meaning of the story. He insisted that he did, although he admits to us that he did not. Left implicit is that he understands the meaning now: not the sophomoric glee of profanity, but the horrifying realization that we are living in a world being consumed by assholes.

El Akkad’s own fiction developed out of his growing disillusionment with the value of liberal ideals—not necessarily in themselves, but in how they were deployed along such geographic fractures. As a journalist, he tells us in One Day, he saw repeatedly what the supposedly moral system of the West had created. Day in and day out, in Canada, in the United States, in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Guantánamo, he saw that the West was not in fact attempting to act on its moral values. To the contrary, it was speaking a language of morality that had nothing to do with the brutality of how it policed the world.

It is this that El Akkad finds most galling. Growing up, he learned that many people come to expect cruelty and indifference from their governments. But cruelty and indifference packaged in the language of care are what he cannot stand. And in this loose world where values are never materialized, “every ideal turns vaporous the moment it threatens to move beyond the confines of the speeches and statements.” El Akkad relates that an editor once told him to revise a speech given by an imperial president in American War because it was too “transparently insincere.” The speech was taken almost verbatim from one that Barack Obama had given in Cairo.

American War is, among other things, a brilliant allegory of the local resistance to American-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The novel is set in the 2070s and 2080s, when, after the passage of the Sustainable Future Act, the United States bans fossil fuels (obviously far too late—the entire East Coast has already flooded, and the new capital is Columbus, Ohio). The Southern states rebel again, insisting on their right to burn petrol, and so begins the second Civil War. The story is told largely from the point of view of a black woman named Sarat. As a child, she is made an internally displaced person by the war and lives an austere life at a refugee camp that is eventually raided to clear out supposed terrorists. Her mother dies in the raid. Sarat gets recruited to fight for the South although she is indifferent to the cause of petrol; it is simply a matter of survival and revenge.

Through the narrative, El Akkad scrambles the reader’s subjective identifications. Rather than trying to create a sympathetic character directly in the context of the War on Terror, a war that many opposed, he pushes us to consider what we would do for a cause dear to our hearts. Would we support a war against the South to end petrol usage, knowing full well the cycles of vengeance and terror that war always brings with it? His brilliance resides in the relentlessness with which he tracks our contradictions.

El Akkad’s second novel, What Strange Paradise, reveals the continual dissolution of his belief that nice words devoid of political efficacy carry meaning. The story follows Amir, a Syrian refugee child, whose ship crashes ashore on a Greek island. He seems to be the only survivor. A young girl on the island, the improbably named Vänna Hermes, finds him and shepherds him to safety. It’s not a spoiler to say the obvious: that her namesake, Hermes, escorted the souls of the dead; that the child is already dead; and that what we read is a fantasy of care, a fantasy of what would happen if we actually lived our morality.

In One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, El Akkad narrates how the last vestiges of his faith in the West cracked around Gaza. The book began in October 2023 and took off from the viral tweet that became its title—a strange future perfect sentence predicting that people would one day reflect on the devastation in Gaza in the same way that now everyone was always against apartheid in South Africa. If there is a reason to write, if there is an extent to which writing matters materially even when it fails in the moment, perhaps it is here, in the record of actual resistance and actual cowardice that it leaves for the future.

From the beginning, this is a book about writing and about language—their power and their failure. We start in medias res, almost picking up from where What Strange Paradise left off. A “fog-colored” girl buried under rubble is the only survivor of an attack. People are trying to say things to soothe her, or to prepare her for what is to come. They use Arabic expressions—Mashallah, Inti zay el amar—that El Akkad tells us can’t be translated, not because the words don’t exist, but because the histories and emotions behind them cannot resonate for someone who has not grown up hearing them.

And yet he will try to make us understand. Of the latter phrase—literally, you are like the moon—he asks us to try to hear that a man is telling this “girl who lived when so many others died that she is beautiful beyond the bounds of this world.” There, in that phrase, in that translation, one hopes that even the most callous must do more than feel something—that they must rearrange their lives to stop this from happening.

This is the book’s perpetual two-step. Step one, language fails. It fails to be translated even within its own terms of sounds and markings. And so of course it fails in its task to get someone who is not there with this child to rearrange their lives so as to save her. El Akkad knows that universal concern is a lie, that novels do not create globally empathic people, that all treaties and treatises are crushed under gunpowder and steel. He knows that telling this story, with all the power of his language, cannot stop the war.

But then, step two, we must still use language to try to end the war. Language is all that El Akkad, and many of us, have to try to make these experiences real, to try to make people understand something that they refuse to understand. He still believes in the dream of a united world that embodies equality, that engenders people who care equally for each other no matter where they are from, that is no longer hemmed in and eviscerated by moral scarcity. He knows that he has no choice but to push for this world.

So he keeps telling us stories, hoping they might help get us there. He tells us of his family fleeing Egypt for Qatar, and then Qatar for Canada. He tells us of his dreams of the West, of free speech and democracy and liberalism as an embodied way of life where he can choose how to be, what to say. He tells us that he has no false consciousness about the cruelties of where he came from, that he knows it is ruled by autocrats who have no more concern for Palestinians than the extent to which supporting them subdues domestic rebellions.

Then he tells us about the path he has taken to become disenchanted with everything his younger self sought and held dear. He learns quickly that, in his privative phrasing, one finds the “harbor never as safe as the water is cold.” And he sees that Western liberalism is not a development of fiction, of narrative’s capacity to expand our ability to see through the eyes of others. Rather that very idea is itself a fiction: “the magnanimous, enlightened image of the self” comes with a “dissonant belief that empathizing with the plight of the faraway oppressed is compatible with benefitting from the systems that oppress them.”

El Akkad refers to the belief that our empathy makes us righteous even as we benefit from an uneven world as a “fortress of language.” Such fortresses “pen” some lives in a permanent elsewhere, caged on the other side of morality—“a world in which one privileged sliver consumes, insatiable, and the best everyone else can hope for is to not be consumed.”

For the young El Akkad, it was “enough” for there to be pockets of liberalism accompanied by a general desire for freedoms to spread noncoercively. It was the job of morality to care about other people and the job of governments to put that care into action. But he learned all too quickly that there was a profound geographic fracture in our moral vision.

Everyone cares, of course, about the child being bombed. The penury of being human is that too often what follows is a second moment, a hideous and repressed moment that we rarely dare to speak aloud, when people think, “Oh, but if some child has to be bombed for the world order to continue, I don’t want it to be my child.” The deepest problem of moral scarcity that El Akkad traces occurs not when one cares about a limited number of people. It is rather this belief that life can only be good for some, that one side will always be consumed.

If we don’t confront and overcome this second moment, the goal of politics is no longer seeking justice, but rather ensuring the right to consumption—while maintaining the language of justice. “It is not without reason,” El Akkad writes, “that the most powerful nations on earth won’t intervene to stop a genocide but will happily bomb one of the poorest countries on earth [Yemen] to keep a shipping lane open [the Strait of Hormuz].” Never mind that ships in the strait would not have been targeted if, instead of bombing Yemen, the United States stopped sending bombs to Israel. This is the perverted moral calculus of our age. Some lives must be made good, no matter the cost to others, no matter the logic or truth of any of it.

For El Akkad, in his relentless criticism, the hideous logic of moral scarcity touches all of us, whether we believe in it or not, because we are social creatures whose existence is not redeemed by our beliefs. We are also defined by social forces outside of our control. He praises those who take a moral stand, but he does not want us to imagine our innocence because of it. We can make known our desire for the world to be otherwise, but we can’t dissolve our material connections to atrocity. The citizens of the West are paying for these bombs regardless of our desires. So what is the point of our morality, even our global justice thinking? Hence El Akkad’s repeated questions: “What is this work we do? What are we good for?”

He retraces his history trying to find an answer. At one point, he rediscovers Smith’s thought experiment. A snow-laden tree crashes into his deck, destroying it. Twelve hours earlier, his daughter had been playing on the deck. He had been reading for months about fog-colored children being pulled from rubble, but nothing felt as intensely painful as this near miss. Later he remembers a night he had to take her to the hospital, and even though she was fine, he had never been more afraid in his life. He concludes: “I don’t know how to make a person care for someone other than their own. Some days I can’t even do it myself.”

Perhaps Aristotle wasn’t entirely wrong—we can’t care for the whole world, because caring means providing more attention to a few people than we could possibly give to everyone. But that doesn’t mean we can live happily with our role in destruction. What we need is not endless empathy, but simply a world that doesn’t require extra care for entire populations. A world that provides goodness for everyone. A world that permits feeling more afraid when your child is in the hospital because there are not whole countries of children being decimated.

This doesn’t mean empathy is entirely compromised in El Akkad’s view, only that it is not enough. He is not the first to criticize empathy for lacking the efficacy to shift our politics. He joins contemporary critics like Isabella Hammad and Aruna D’Souza, and they have predecessors. Although the feeling of empathy may be as old as Aristotle, the word itself is relatively new. It first appeared in English in 1909, as a translation for the German Einfühlung, in-feeling. The verb einfühlen—to feel one’s way into—has existed for centuries, but the idea of a specific capacity for this feeling process wasn’t given language until about a century ago.

El Akkad does not discuss this history, but it’s interesting to note that one of empathy’s earliest critics was Martin Buber, the German-Jewish religious philosopher who was also a Zionist, but a kind rarely remembered today: a cultural Zionist, critical of ethnonationalism, anti-imperial, and hopeful that a binational socialist state could arise in Palestine, supplanting both the British and the Ottomans and making an egalitarian home for two peoples. For Buber, empathy was the wrong idea to help realize this ideal. He argued instead for Umfassung, often translated as inclusion or embrace.

While with empathy one projects oneself into another’s life, embrace reveals that one is already part of that other life. This may include already being part of its destruction, which is what El Akkad in One Day asks us time and again to see. What others need is not our fellow-feeling, but our acts of redemption, our ability, by whatever means we can, to make a decent world for everyone. That was once Buber’s hope for Palestine, and it is El Akkad’s today.

This ethic of entanglement may ultimately have no more practical efficacy than professed empathy, but it might at least make the hypocrisy harder to swallow. It’s one thing to say, “Of course I care about that other child, but there’s nothing I can do.” It’s quite another to say, “Of course I recognize that I am part of that child’s murder, but there’s nothing I can do.” We are capable of a great many hypocrisies, but perhaps such an understanding could finally crack through.

Until it does, El Akkad suggests that we have no choice but the two-step: recognize our limitations but continue to push everyone to confront their entanglement. Even those who are already doing this must come face to face with the political facts that overwhelm their moral refusal. We can neither lose sight of paradise nor ignore the journey through hell. We struggle on with the fragments of political action that we can muster in this broken world, recognizing our role in destruction, and knowing full well that we cannot immediately end the slaughter, that our words and ideals have limited power in the face of money and munitions.

What is this work we do? What are we good for? In part, we help create a certain clarity of vision—knowing what is wrong in this world and how it could be better. A simple place to start: not murdering any civilian, anywhere. But there is no obvious path to achieving even that basic moral truth. El Akkad leaves us with an uneasy method, reminding us that our task is as impossible as it is necessary: “We hurtle toward the cliff, safe in the certainty that, when the time comes, we’ll learn to lay tracks on air.”

Avram Alpert is a lecturer in the Princeton Writing Program and the co-director of the Interdisciplinary Art and Theory Program. His most recent book is The Good-Enough Life.