The Conquerors of Tomorrow

The Conquerors of Tomorrow

The tragic inheritance of the Shoah is that the victims of violence are often its next perpetrators.

The World After Gaza: A History

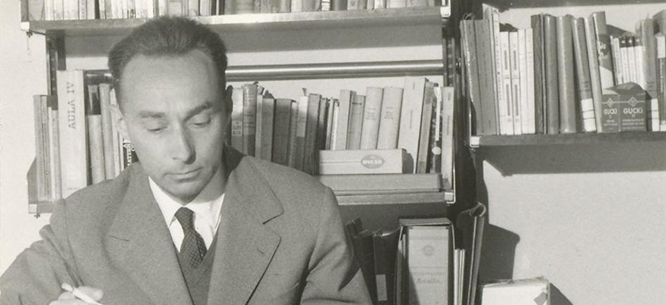

by Pankaj Mishra

Penguin Press, 2025, 304 pp.

There’s a clue, hidden at the end of The World After Gaza, as to why Pankaj Mishra invokes the voices of Shoah survivors to critique the Israeli government’s murder of Palestinians today. It is a quote from the French philosopher Simone Weil, which appears as the epigraph to his final chapter. Writing during the Second World War, Weil knew that war collapses the distinctions that separate victims from perpetrators in ordinary times. Amid this ambiguity, Weil warned, the writer’s duty was to “seek a conception of equilibrium,” remaining “ready to change sides like justice, ‘that fugitive from the camp of conquerors.’” The writer must stand with the defeated today, ready to oppose them as the conquerors of tomorrow.

Mishra’s moral argument in this book works from Weil’s insight: that the victims of violence are often its next perpetrators. He believes this to be the true and tragic inheritance of the Shoah—not (as Benjamin Netanyahu would have us deceived) that “those who are strong and strike first deserve to live.” In embracing Weil, Mishra intrudes upon an internal conversation among Jewish thinkers about how to rightly remember the Shoah and so honor its victims. He locates the Jewish experience of rootlessness in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries within the broader emotional history of decolonization. In so doing, he risks conflating his own history, as an Indian, with that of Israel-Palestine. But there is historical weight behind his analysis. Colonialism, he argues, was the testing ground for the modern forms of state violence later mastered by totalitarians on the dark continent of Europe in the 1930s and ’40s—echoing an argument first made by Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism. (Remember that Hitler wanted to make Eastern Europe into a colony for Germany, the veritable equivalent of India for Great Britain.) Mishra thus recovers a forgotten form of solidarity between Jews, other peoples who suffered modernity’s evils in the twentieth century, and Palestinians currently being killed by Israel in Gaza. Throughout, Mishra remains steadfast: violent ethnonationalism is the common enemy that must be opposed.

Still, he never fully articulates what this haunted inheritance means for Israel, Hamas, or those of us complicit in Western democracies. He hints at a powerful question without addressing it head on: does violence—regardless of its source—always deform the moral agent, as Weil believed it did?

Since delivering “The Shoah after Gaza” as the Winter Lecture for the London Review of Books in February 2024, Mishra has found ...

Subscribe now to read the full article

Online OnlyFor just $19.95 a year, get access to new issues and decades' worth of archives on our site.

|

Print + OnlineFor $35 a year, get new issues delivered to your door and access to our full online archives.

|