Lula’s Unfinished Democracy

Lula’s Unfinished Democracy

The Brazilian president once argued that democracy will founder where inequality reigns. Today, he sees fighting inequality as democracy’s animating mission.

Brazil marked four decades of democratic civilian rule earlier this year. From 1964 to 1985, Latin America’s largest nation was governed by generals who illegally seized and exercised power in the name of anticommunism. By the early 1980s, faced with an economic crisis, social unrest, and growing opprobrium abroad, military officials sought to gradually unwind the regime on their own terms. They issued a broad, self-serving amnesty and allowed for the return of multiparty democracy, inaugurating an era of rampant party proliferation and contentious partisan dispute that deepened Brazil’s democratic character even as it allowed the outgoing regime to avoid facing a unified opposition. It was at this moment that the Workers’ Party (PT) was born.

In 1985, Tancredo Neves of the Brazilian Democratic Movement party, born from what had been the only sanctioned opposition party during the dictatorship, was indirectly elected the country’s first civilian president in twenty-one years. Neves was an experienced senator with solid anti-dictatorship credentials, but a moment of triumph became one of mourning when he fell ill and died before being sworn in, leaving power in the hands of his running mate, José Sarney, a longtime ally of the military regime. Sarney’s leadership raised fresh doubts about how real or lasting Brazil’s democratic transition would be. It was in this uncertain climate that Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a former union leader who was central to the formation of the PT and already one of the loudest voices on the left, consolidated himself as a leading proponent of democracy’s transformative potential.

In a 1985 interview, Lula was asked whether Brazil’s new democratic system was delivering real change for working people. Skeptical of the narrow, elite-driven transition then underway, Lula criticized the idea that simply holding elections was enough. “Do you think the janitor at your newspaper enjoys the same democracy you do,” he asked the interviewer, “just because you both live under the same regime?” When the interviewer replied that, in formal terms, yes—each person’s vote counts the same—Lula pushed back. “No,” he said, “democracy is not just the right to vote. Democracy is the right to life.” Brazil’s profound inequalities, he argued, meant that the tangible benefits of democracy accrued only to a small percentage of the population. The promise of equality, social mobility, and effective political participation was mostly moot for poor and working-class people. Democracy could not be said to exist under such conditions, Lula insisted.

Forty years later, Lula is serving his third term as president, after leading the country from 2003 to 2011. On the comeback trail in 2022, he ran as the face of a pro-democracy front that aimed to defend the country’s imperfect institutional order against Jair Bolsonaro’s reactionary onslaught. Lula recently compared Brazil’s civic progress over the last four decades to the radical upheavals of the twentieth century. While the Russian and Cuban revolutions were led not by workers but by “intellectuals, political activists, students,” in Brazil “workers could organize a party and reach the presidency of the republic.” That achievement “was not on the political calendar,” he asserted. “And that is why I value democracy so much.” Over four decades, the president’s long-standing commitment to popular sovereignty has remained constant, even as the political terrain around him has changed. He no longer seems certain that democracy will founder where inequality reigns. Instead, he argues that fighting inequality is democracy’s animating mission.

Democracy will face another test in Brazil’s presidential race next year. One of the central questions in Brazilian politics today—a question that has haunted the country since the end of military rule—is whether the nature of the country’s democratic order itself enables the persistence of authoritarian threats. Built through compromise, the post-authoritarian system prioritized stability over transformation, resulting in institutions that are procedurally democratic but structurally conservative. And while Lula earned unprecedented good will from broad swathes of the population during his first stint in office, a period in which inequality fell and the economy grew, the years that followed were characterized by crisis. Electoral competition took place against the backdrop of rising mistrust in institutions and economic hardship, conditions ripe for the kind of anti-system politics that lifted Bolsonaro to power in 2018.

Assembling a broad front against Bolsonarismo was the central thrust of Lula’s 2022 campaign. This helped him win, but it set up a very difficult framework for governing. As a result, his third term has failed to deliver many major policy innovations, aside from a tax reform that had eluded presidents for years and other relatively minor accomplishments. This administration has been defined by a frustration and defensiveness that stand in stark contrast to the policy dynamism of his first two terms. Lula’s main appeal going into next year’s race will be that he has unequivocally stood up for the rule of law, but he has been unable to win major victories for working people.

Lula became a great statesman by investing himself in the process of building up Brazilian institutions over several decades. The transition from military rule in the 1980s and the years since his election to a third term in 2022 are two of the most crucial periods in this project. They reveal that it is Lula’s ability to invest the machinery and procedures of formal democracy with popular meaning—linking democratic process to material improvement and social inclusion—that allowed him to command lasting political support.

This approach has always been rooted in an optimistic belief in the power of collective action, but also entails a willingness to harness righteous indignation. For the first half of his third term, the latter had largely been missing from Lula’s rhetoric. This changed in early July when U.S. President Donald Trump posted a letter to Lula on his Truth Social account threatening a trade war as a result of the Brazilian government’s prosecution of Bolsonaro for undermining the 2022 election, and its insistence that U.S. social media companies operating in Brazil abide by local laws (Trump and his allies consider this an unacceptable form of censorship). Suddenly, Lula has a galvanizing message to unify Brazilians of every stripe: Brazil is a sovereign nation that will not be pushed around.

While it remains to be seen how this dispute will play out in the long term, Lula’s prior experience has equipped him with the skills and credibility to stand firm in defense of Brazilian democracy. As the country looks toward the 2026 election, in which Lula plans to run once again for president, he stands as a courageous defender of Brazil’s sovereignty. That reputation alone, however, might not be enough to protect the country’s democratic order from novel threats ahead.

The Upstart

In 1964, with the active support of the Lyndon B. Johnson administration, the Brazilian military seized political power in Brazil. Two years later, Lula began work as a lathe mechanic at Indústrias Villares, one of the country’s leading metallurgical companies in the industrial outskirts of São Paulo. Unlike his older brother, who was a member of the Communist Party, Lula was uninterested in politics. It was a dangerous time to be a militant and a deeply uninspiring moment for formal politics, constrained as they were by the heavy hand of the generals in power. By his own admission, the youthful Lula was much more interested in dating and nurturing friendships with other workers.

The politics of the workplace were not especially engaging for the future president either. Lula saw the Metalworkers’ Union as unresponsive and essentially conservative, a relic of a much older generation content to have any representation at all. At his brother’s prodding, however, he begrudgingly ran for and won a small role in the union administration in the late 1960s. Gradually, he came to see the union as a tool for defending the interests of workers in an economy producing astronomical growth rates without decent wages. His sharp political instincts and natural charisma allowed him to thrive as a leader, and in 1975 he was elected president of his influential local, representing over 100,000 workers.

As the economy began to slow in the late 1970s, it became increasingly clear to workers and union leaders that the military regime was systematically underreporting inflation in order to avoid adjusting wages accordingly—a policy known as arrocho salarial, or wage squeeze—which fueled the radicalization of the labor movement. In 1977 an article in a major newspaper proclaimed the emergence of a “new unionism in São Bernardo.” New Unionism became shorthand for the more assertive, autonomous, and overtly political labor movement Lula came to embody as he rose to national prominence. He sharply criticized the corporatist structure of organized labor inherited from Getúlio Vargas, who first ruled Brazil as a dictator from 1930 to 1945 and then as an elected president from 1951 until his suicide in 1954. For Lula, the challenges facing workers did not begin with the military coup of 1964 but with the Revolution of 1930 that brought Vargas to power.

As a spokesman of the New Unionism, Lula called out a generation of labor leaders—many of whom were not drawn from the industrial rank and file—who prioritized maintaining friendly relationships with management or political elites over advocating for the rights and interests of their members. This critique, often overlooked in Lula’s biography, directly shaped his political identity, eventually leading him to embrace the creation of a political party of, by, and for workers, instead of the apparatchiks who had long dominated the parties that claimed to speak for working people, Vargas’s Brazilian Labor Party chief among them. Challenging the authoritarian system put in place by the dictatorship came next.

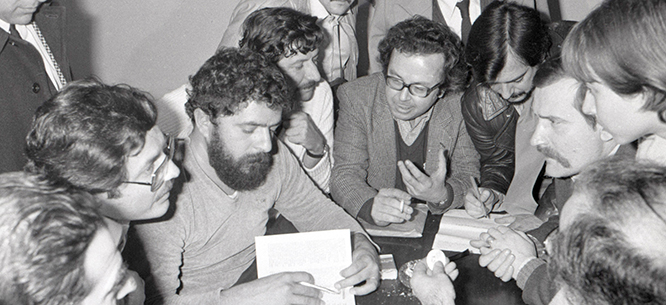

In 1978, at the age of thirty-two, Lula led a massive metalworkers’ strike in the industrial outskirts of São Paulo to protest poor working conditions and the dictatorship’s anti-worker policies. Similar stoppages followed in 1979 and 1980. The strike wave spread to automakers’ factories, and Lula became a national figure in the struggle to restore Brazilian democracy. Interviewed in 1978, he framed his ascent as inseparable from his class origin. As a union leader, he simply said “what any worker would wish to say if he were placed in front of a microphone.” His insistence that he was a worker first, no better than his peers for all the power of his office, became a lasting and potent part of his political appeal. Lula claimed his allegiance to workers was not ideological but principled. “The working class should never be an instrument,” he said. Rather, as the majority of the country, the working class should be treated as “a living force with a real voice.” (Brazil’s deindustrialization in recent decades has weakened the relative power of unions, rendering that voice somewhat less discernible. Lula endures as an icon—critics might say a relic—of an earlier period of dramatic worker empowerment.)

Lula also placed himself within a broader camp critical of the corporatist labor system inherited from Vargas. “I believe that the labor movement before 1964 was used very much politically,” he said in 1978. “They probably did a lot of politicking instead of really defending workers.” Lula promised a different path, presenting himself as one of a new crop of labor leaders “willing to make any sacrifice in the defense of the working class that they represent.” His early political identity was singularly focused on defending the economic importance of industrial workers.

Lula’s commitment to workplace democracy inspired him to take on the authoritarianism of national politics, a system Lula insisted would never deliver material gains for working people. When the dictatorship decreed the return of multiparty politics in 1979—a tactic meant to divide an opposition camp reenergized by New Unionism in the wake of the violent destruction of the armed left—Lula and others concluded that working people needed their own political party to advocate for them in a system that had historically cared little for their input. They formed the PT, which quickly became a vehicle not only for protest but for electoral participation.

As a union leader and politician, Lula played a salutary role in the democratizing wave that shook Brazil in the 1980s and toppled the military dictatorship. He helped ensure that workers were a visible part of a coalition uniting labor, students, clergy, and disillusioned elites around a demand for democracy. Indeed, what made this coalition effective was its ability to combine grassroots disruption with institutional pressure, without demanding ideological purity from all participants.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Lula, along with many others, built the PT into a national force. He emerged as the party’s most visible leader, crisscrossing the country to articulate a vision of governance that fused grassroots activism with engagement in the formal political process. The future president helped steer Brazil’s democratic transition as a federal deputy in the 1988 Constituent Assembly, where he advocated for stronger social protections and labor rights in the new constitution. He ran for president and lost three times—in 1989, 1994, and 1998—gradually moderating his platform and expanding his coalition without abandoning his core commitments. He extended his political vision beyond labor rights to embrace a social agenda rooted in economic justice, institutional reform, and participatory democracy.

The Elder Statesman

Almost fifty years since he became a national figure, Lula remains an icon of pragmatic progressive governance in a stubbornly conservative political culture. As president from 2003 to 2011, he oversaw economic growth that dramatically reduced extreme poverty. When Lula left office with an 83 percent approval rating and handed the reigns to Dilma Rousseff, his chosen successor and Brazil’s first woman to serve as president, Brazilian democracy was far more stable and inclusive than it had been when the PT was founded. Institutional solidity seemed to promise that the country would continue its slow but steady climb toward global influence. What followed instead was a reactionary groundswell against progressive political forces—especially Lula’s PT—which led to Dilma Rousseff’s capricious removal from office, Lula’s arrest at the hands of a partisan judge on charges of corruption, and the election of Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right extremist who threatened the nation’s democratic order in a way no leader had since the dictatorship.

After almost a decade of gains for the right, history turned abruptly once again. The charges against Lula were annulled in 2021 after it became clear the presiding judge in his case colluded with the prosecution, and he was free to launch his sixth presidential run in 2022. (Brazilian law states that presidents can serve only two consecutive terms in office but may do so multiple times.) Building on anger at Bolsonaro’s incompetent leadership, Lula assembled the largest coalition of his career; more than a dozen parties backed him, against Bolsonaro’s five. The framing of the race as a binary choice between democracy and authoritarianism resonated with the country’s political center and center-right, not just the left. “There are many people who were never part of the PT and who participated in my government. And that is how it will be,” Lula asserted. “It will not be a PT government, it will be a government of the Brazilian people.”

Lula prevailed with 60 million votes to Bolsonaro’s 58 million. It was the closest election he had ever won—hardly the knockout blow against the far right that many had hoped for. And despite presiding over a calamitous response to the pandemic and earning universal condemnation for Amazon deforestation, Bolsonaro helped get several key allies elected at different levels of government. Even in defeat, he demonstrated surprising strength, and his base remained committed. As historian Carlos Fico, one of the leading scholars of the dictatorship, put it: “The Bolsonaro years have been a kind of reality check for those who considered Brazilian society to be very much in tune with democratic principles. This is what we call socially existing authoritarianism. There is a significant portion, around 20%, who agree with an authoritarian political profile that devalues human rights.”

On January 8, 2023, a week after Lula’s inauguration, Bolsonaro supporters staged an insurrection in Brasília, drawing instant comparisons to the U.S. Capitol invasion two years prior. Enraged by Bolsonaro’s defeat, rioters clad in the national colors stormed key government buildings and did millions of dollars’ worth of damage. Lula was quick to frame the insurrection as an attack on democracy and, by extension, the sociopolitical and economic agenda that he stood for. In his address to the nation shortly after the riots, Lula asserted that the mob was almost certainly paid for in part by actors linked to deforestation in the Amazon, which a subsequent journalistic investigation bore out. It has since become clear precisely how far up anti-democratic conspiracies reached in the aftermath of Lula’s election. Lula has doggedly pursued charges against Bolsonaro and his supporters, and the former president may well end up behind bars for his part in the insurrection. Brazil’s electoral court has barred Bolsonaro from seeking the presidency in 2026. But Lula was supposed to spend over a decade in prison rather than the 580 days he actually served before winning another presidential election. The danger of Bolsonarismo has not dissipated.

Lula’s Legacy

The day after the insurrection, Lula reaffirmed that democracy was not an abstract ideal but the only viable path to confronting Brazil’s extreme inequality. He argued that guaranteeing every Brazilian a dignified life, including things as basic as regular meals, depends on the survival and deepening of democratic institutions. This is at the heart of how Lula has long defined democracy itself: not just as a procedural parlor game but as a mechanism for delivering people tangible benefits. But if in earlier terms Lula launched expansive, transformative programs like Bolsa Família, ProUni, and Minha Casa, Minha Vida—policies that revolutionized social welfare by providing direct cash support to poor families, expanded access to higher education through scholarships, and increased affordable housing opportunities for low-income Brazilians—his administration must now rely largely on symbolic gestures and targeted messaging to rally support around modest redistributive measures.

As the presidential campaign cycle heats up, Lula can highlight material achievements like a real increase in the minimum wage (above inflation), record low unemployment, and an increase in taxes on the wealthiest Brazilians in order to exempt individuals earning up to R$5,000 per month from paying income taxes. These are substantial policies, in a context defined by polarized political sclerosis, but they represent small victories when compared to the array of transformative policies implemented by prior PT governments.

There has been a dearth of ambitious, creative new policy thinking in the PT since 2023, which speaks to the constraints of this moment. Lula has been frequently frustrated in his dealings with a deeply fragmented Congress, which is much more powerful today than when Lula first came to office. It is also dominated by conservative interests and a bumper crop of vocal right-wing agitators elected in large part to gum up the works. No single party commands a majority, making alliances unstable and even more transactional than usual. This political landscape has incentivized individual legislators like never before to prioritize local or partisan interests over items on the national agenda. A key driver of this shift has been the rise of emendas impositivas, or budget amendments that legislators can now pass and execute independently, forcing the executive to disburse public funds at their discretion with almost no transparency. The problem was exacerbated by Bolsonaro’s use of the opaque orçamento secreto (secret budget) to entrench a powerful conservative bloc in Congress, weakening democratic accountability and depriving his successor of the institutional tools needed to govern effectively. It is one of his most damaging legacies.

Congress has also forced Lula to scale back or abandon several of his initiatives. For example, a major component of his third term agenda has been a renewed push for “social justice” through tax reform—specifically, by raising rates on the wealthy and online betting platforms to fund tax exemptions for low-income and middle-class earners. While the executive has framed such moves as a necessary redistribution, Congress resisted, even overturning a presidential decree that modestly raised the tax on financial transactions. This defeat sparked not only public frustration from Lula but also a successful decision to challenge the legislature in court. Up until this year, the administration had managed to work surprisingly well with legislative leaders on certain issues with broad buy-in such as the need for a simpler tax code. As the government has pressed on thornier topics this year ahead of campaign season, however, the relationship has become much less productive.

Within the PT, there are intense debates about where to go next, highlighted by the recent election to determine the new head of the party. Many in the PT support Lula’s big-tent approach to governance as a necessary defense against the right. Fernando Haddad, who served as education minister during Lula’s first administration and finance minister in the second, has described the president’s strategy as “a coalition to prevent the greater evil.” Some candidates for national leadership, by contrast, argued that Lula’s strategy risks alienating core supporters. Valter Pomar, Romênio Pereira, and former PT leader Rui Falcão have warned that unless the government sharply changes course and adopts a more aggressive leftist posture, it could face defeat in 2026. They called on the government to soften its commitment to a balanced budget, to invest more in a broader array of public programs, and to sharpen the rhetoric against the government’s opponents.

Edinho Silva, Lula’s preferred candidate to lead the party, argued that the president is “a hostage of a Congress driven by earmarks,” suggesting the government’s difficulties reflect deeper institutional constraints. But Silva, who was elected as the PT’s new leader on July 7, nevertheless insisted the party must continue reaching out to more conservative elements in Congress to recompose the broad front strategy that succeeded in 2022. At stake is not only the vision for how the Lula government should proceed over the next year in order to win another term but also how to ensure the party’s short-term survival and long-term renewal.

Perhaps the only safe conclusion to draw from Lula’s legacy at this point, then, is that he has stood on the side of institutional democracy against the caprice of authoritarianism when it has counted most. This may seem small-bore to critics on his left, but it is not something that can be said of many left-wing Latin American leaders since the end of the Cold War. By the end of 2026, Lula’s PT will have governed Brazil for a combined total of almost twenty years, delivering real gains in poverty alleviation and a consistent commitment to democratic institutions; millions of Brazilians have benefited materially over that time, with vanishingly few worse off than before. The same cannot be said, for example, of Venezuela under Chavismo or Daniel Ortega’s Nicaragua. Indeed, Lula’s reelection campaign will almost certainly emphasize the longue durée of the PT’s time in power, arguing that people are better off when the party is in office. Tending to democratic institutions is imperative for those who want to serve the common good.

It is unclear if that will be enough to win in 2026. Voters will more likely compare their current state to what they believe it could be rather than what it was two decades ago. Despite solid economic numbers, Lula’s approval ratings reached the lowest point he has ever recorded halfway through 2025. In fending off the right, he has actually narrowed the bounds of what feels politically imaginable. The task ahead may require more confrontation with powerful interests, not less. Finding a way to make such a move politically viable—and doing so do while respecting democratic norms—is a tall order, but one that should be at the core of the PT going forward.

Ironically, help may come from abroad. In a context of domestic gridlock and limited legislative gains, Trump’s threatened trade war against Brazil has unexpectedly reset the political chessboard in Lula’s favor. The looming imposition of tariffs and rising trade tensions have given him an external threat around which to rally nationalist sentiment and unify a divided coalition. Lula has categorically refused to break Brazil’s institutional order to satisfy Trump. But now he looks less like the pragmatic caretaker of a post-Bolsonaro order and more like his combative former self, denouncing global elites and defending the working class against foreign economic aggression. He is tapping into a new source of popular energy, and early polling suggests it is already paying dividends.

More than just a political boost, the trade war offers a chance to reframe the stakes of his presidency not as a slow walk through a legislative minefield, but as a struggle to protect the livelihoods of ordinary Brazilians from external harm. The contrast with Trump, who is deeply unpopular in Brazil, sharpens Lula’s image at home and abroad. Contra the venal authoritarian bully in Washington, Lula is the progressive champion standing up for fairness and shared prosperity. After all, democracy cannot survive on nostalgia alone. It must prove its worth in real time, especially to those who have the least. Lula’s job is not finished.

Andre Pagliarini is assistant professor of history and international studies at Louisiana State University, a fellow at the Washington Brazil Office, and non-resident expert at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. His book Lula: A People’s President and the Fight for Brazil’s Future is out this fall from Polity.