The Voice of a Generation Yawns

The Voice of a Generation Yawns

The Another Self Portrait reissue comes as a vindication of the appropriateness of a “great artist” throwing off as much “product” as the market can bear. No longer a cynic for churning out releases, Bob Dylan is widely seen as wise and generous for sharing more.

In our media-saturated, surveillance-rich era, everyone expects to always have access to us. We carry an irrefutable audience in our palms and in our heads. The attention won’t go away; playing along has become an economic necessity. Under these conditions, exposing yourself can seem like the best way to disappear. The more pictures of yourself you post, the more contradiction you sow. You hope you can escape into the ambiguity.

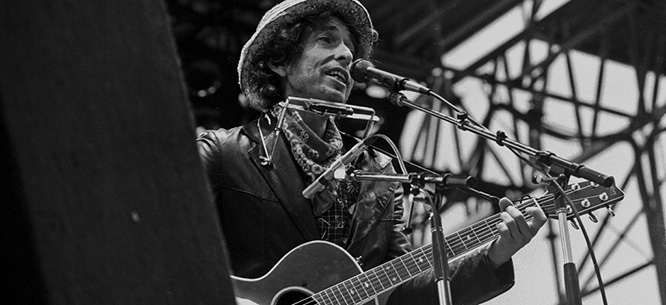

Bob Dylan confronted these paradoxes of the “attention economy” before the rest of us, most notably on his 1970 album Self Portrait, overhauled and reissued last August by Columbia Records as Another Self Portrait. Elevated to an oracle of 1960s youth culture, Dylan found himself subjected to remorseless scrutiny from both disciples and would-be exploiters. After his motorcycle crash in 1966, he undertook a series of attempts to disburden himself of his reputation. He moved with his family to Woodstock in upstate New York, later saying that his “deepest dream” at the time was “a nine-to-five existence, a house on a tree-lined block with a white picket fence.” Turning away from cutting-edge rock, he embraced the decidedly staid genre of country on John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline. Where once his lyrics had suggested world-historic relevance, these new records—featuring inscrutable fables and cliché-ridden love songs sung in an incognito crooner voice—seemed to defy listeners to interpret them. Dylan’s “real thoughts” seemed remoter than ever.

But these strategies only intensified the scrutiny. In his 2004 memoir, Chronicles, Dylan complained of how “rogue radicals looking for the Prince of Protest” showed up in Woodstock. He said he “had very little in common with and knew even less about a generation that I was supposed to be the voice of.” But like a hipster marked by his rejection of the label, Dylan remained the voice of a generation precisely by refusing.

“What kind of alchemy, I wondered, could create a perfume that would make reaction to a person lukewarm, indifferent and apathetic?” Dylan asked himself in Chronicles. He set out to record “something they can’t possibly like, they can’t relate to.” The title of the resulting album, Self Portrait, revealed a new strategy: if he couldn’t escape into seclusion, might he disappear through self-exposure? Could he escape the burden of his superstar status by indulging it, coming across as lazy, indiscriminate, self-satisfied?

For Self Portrait, Dylan adopted a kind of fake kitchen-sink approach, leaving in deliberate errors and bad judgment calls so his decision making would seem random and haphazard. In Chronicles he reports, “I released an album (a double one) where I just threw everything I could think of at the wall and whatever stuck, released it, and then went back and scooped up everything that didn’t stick and released that, too.” He decided to become an oversharer.

In retrospect, it is obvious that this mishmash would do little to dispel the Dylan myth. Once musicians are aggrandized into geniuses, their filler will automatically be interpreted as artistic statements. The less that seemed to be there, the more successfully its truth seemed to have been hidden, demanding redoubled attention. The bizarre result is that Dylan’s best fans have spent the most time listening to his worst music.

The title Self Portrait was “a joke,” he told Kurt Loder in 1984, but the joke was funny because it was true. He was portraying himself as he wanted to be seen—commercial but not co-optable. More a piece of conceptual art than a pop record, everything about the album is suffused with irony. The self-portrait is made up of mostly pointed cover songs (“I Forgot More Than You’ll Ever Know,” “Take Me as I Am (Or Let Me Go),” “Let It Be Me”), a ham-fisted demonstration that the “self” is merely a matter of one’s influences and context. Dylan also covered songs by artists said to be his imitators, offering a reflection of a reflection.

Once musicians are aggrandized into geniuses, their filler will automatically be interpreted as artistic statements. The less that seemed to be there, the more successfully its truth seemed to have been hidden, demanding redoubled attention.

The basic tracks were recorded in a few days, and much of the album has an improvised feel; David Bromberg, Dylan’s accompanist on those tracks, explained that sometimes Dylan “doesn’t know what he’s going to do next,” even in the middle of a take. This suggests he was recording his spontaneous impulses, a willed surrender to contingency, as if that were the way to get to what he truly was. Yet these tracks were extensively overdubbed later, in Dylan’s absence. Self Portrait is thus underfinished and overproduced at the same time, another metaphor for the self. The album also includes a few live tracks from his only concert in these years, a brief set with the Band at the Isle of Wight Festival in August 1969—a gig he seemed to have accepted to underscore his refusal to play a few weeks earlier in his own backyard at Woodstock.

It seems, then, that Self Portrait was a fuck-you to Dylan’s fans on several levels, and some—most famously Greil Marcus—took it that way. But the album may also be regarded as a perverse tribute to them. The album claims the freedom to remake oneself (and to wreck one’s reputation) according to one’s own standard. The message fits with sociologist Theodore Roszak’s interpretation of Dylan as an exemplar of his generation’s embrace of self-expression for its own sake. Dylan’s wasn’t the tentative liberation Roszak optimistically perceived, however, but a prescient retreat into the “Me” Decade. And Dylan modeled this withdrawal for his fans, who were already beginning to drift this way. He presented the path as cavalier and quixotically dignified rather than cowardly and narcissistic. The “deeper level of self-examination” Roszak attributed to 1960s youth became, in Dylan’s hands, an effort to get a flattering look at oneself in a mirror without having to see anything else.

Self Portrait is an emphatic refusal of public accountability. If the album was a “joke,” the joke was on the consumers who bought it. With the Self Portrait sessions reissued as Another Self Portrait, in two different boxed-set configurations, whom is the joke on this time?

After its release, Self Portrait became emblematic of the end of 1960s idealism. Rather than a pop-star vanguard leading a youthful society past postwar conformism to a politically aware collective consciousness, artists turned soul-searching into commercial products. Dylan’s fans, overwhelmed by the collective demands of their own politics, followed his defensive turn away from social engagement. They too could skirt compromise by inscrutably selling out, making ambition a personal mission to get free of other people’s hang-ups and expectations, to self-actualize. This sentiment would blossom in organizations like Erhard Seminars Training (est) and other flowerings of the “human potential movement.” Self Portrait made the case that the sheer will to create and communicate could replace discrete accomplishments. And though the music may have been a disappointment at the time, Dylan’s new approach—mellow country rock with simple lyrics endorsing a conflict-free hedonism—would become a 1970s hallmark, epitomized by the regrettable success of the Eagles.

Greil Marcus documented this desire to mimic Dylan’s retreat in his Rolling Stone review of Self Portrait (the one that begins, “What is this shit?”). This inspired piece of criticism anticipated most of the plausible reactions to the album, and it has certainly done more to render it “legendary” than the music it contains. When Marcus complains that Self Portrait is “such an unambitious album,” “JW”—presumably Rolling Stone editor-in-chief and quintessential boomer Jan Wenner—replies, “Maybe what we need most of all right now is an unambitious album from Dylan.”

And maybe the Another Self Portrait reissue is exactly what Wenner’s generation needs most of all right now: an overambitious attempt to rewrite the past and redeem cynical choices as marks of hidden integrity and irrepressible artistry.

In his original review, Marcus called Self Portrait a “good imitation bootleg,” wondering whether Dylan released it as a response to the Great White Wonder, one of the earliest outtake bootlegs to gain wide distribution. If everything Dylan did was going to be ferreted out and bought up by overeager fans, why should he be careful about what he released officially? In the notes to the 1985 box set Biograph, Dylan himself picks up on this idea and offers it as an alibi for Self Portrait: “I was being bootlegged at the time and a lot of stuff that was worse was appearing on bootleg records. So I just figured I’d put all this stuff together and put it out, my own bootleg record, so to speak.”

Now Another Self Portrait comes out as Volume 10 of his official bootleg series, an authorized bootleg of an authorized bootleg. Marcus, who decried the original record as a commercial cheat and the “closest thing to pure product in Dylan’s career,” provides the liner notes.

It’s no surprise that a record company would revisit one of Dylan’s more misunderstood periods to present a new Dylan to be lionized: Dylan as the great interpreter of others’ songs. It’s a bit more surprising to see Marcus cooperating. “Alternate takes have been used as a graveyard rip-off to squeeze more bread out of the art of dead men or simply to fill up a side,” he declared in his 1970 review; now he enthuses about his temptation “to get lost in the tangles of the previously unheard versions of ‘When I Paint My Masterpiece’ or ‘Spanish Is the Loving Tongue.’”

In 1970 Marcus predicted an onslaught of collections of alternate takes from bands “who want to maintain their commercial presence without working too hard.” The record industry has delivered on this, reissuing not only alternate takes but often the same recordings of favorites in “improved” mixes on new media formats, demanding fans buy the same albums over and over again. Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, for instance, has been reissued on CD, SACD, and in an “Original Mono” version.

But what particularly troubled Marcus about outtake collections was not the naked cash grab (though that’s what he called the original Self Portrait) but the idea that certain geniuses were above the requirement of issuing finished statements and could get by with rough drafts. “The auteur approach allows the great artist to limit his ambition, perhaps even to abandon it, and turn inward,” Marcus wrote. “To be crude, it begins to seem as if it is his habits that matter, rather than his vision. If we approach art in this fashion, we degrade it.” If art is only meaningful within the context of the artist’s career—or alternatively, if the real work of art is the artist’s life—then the individual releases are just souvenirs. They don’t have to be aesthetically compelling (let alone politically engaged) to be interesting, or good.

The Another Self Portrait reissue comes as a grand vindication of the auteur approach, of the appropriateness of a “great artist” throwing off as much “product” as the market can bear in the name of rounding out our understanding of his greatness. No longer a cynic for churning out releases, Dylan is widely seen as wise and generous for sharing more. The album, resurrected in an even more completist version than the exhaustive original, stands as retrospective proof that he could do no wrong, even when he was self-sabotaging—and by extension, neither could the generation that made an idol of him. The reissue’s revisionist history shows how aesthetic recuperation can retroactively rationalize a kind of political apathy.

The chief pretense for this reissue is to present tracks from the Self Portrait sessions (along with a few strays from Nashville Skyline and from the New Morning sessions that quickly followed) without producer Bob Johnston’s widely despised overdubs. The reissue caters to the desire of Dylan’s fans (and his label) for more content in part by simply subtracting elements from songs they already know. And critics have lapped it up. Minus the Mantovani, these songs are “revelatory,” revealing the brilliance of Dylan the interpreter and folk revivalist, presaging by two decades his career-redeeming “unplugged” albums of folk and blues standards, Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong. In Rolling Stone, David Fricke calls it “one of the most important, coherent and fulfilling Bob Dylan albums ever released.” Pitchfork’s Mark Richardson describes some of the outtakes as “brilliant showcases of [Dylan’s] ability to inhabit old material and make it his own.” Ben Greenman’s New Yorker review calls the reissue “an illustration of Dylan’s vast command of the folk song, a laboratory for transforming some of his most familiar hits, and a testament to his powers as an interpretive singer.” What is this shit?

Sometimes the mouthpiece of a generation is most representative when it is yawning.

This isn’t to say Dylan’s singing on Another Self Portrait is not compelling or that his session musicians are not sympathetic and bracing. But the original versions of the Self Portrait songs were arguably already as good as they needed to be, as well as more interesting as historical artifacts. The stripped-down versions are efforts to obliterate history, as if they represent a choice that Dylan equally could have made then. With clean twenty-first-century mixes as a pretense, we can all transcend our times like Dylan wanted to then. We can become real lovers of song, connoisseurs of the artisan at his bench.

But no mode of listening is ever free from political questions—who gets to make art, who gets to listen, who gets to afford it. There is only the indulgent trick—bathed in nostalgia for one’s own lost, uncompromised, pure self—of thinking you are above it all.

Marcus originally heard the Dylan of Self Portrait as a detached and indifferent cynic who delivered rote, “formal” performances. He argued that Dylan belonged to his fans because of his talent and chided him for shirking his “vocation,” implicitly demanding more “genuine” emotion from him. But what could possibly be genuine in this context? What performance of sincerity could have actually satisfied fans who expected Truth, available over the counter? Marcus insisted that you can’t resign from being the voice of a generation once you’ve spoken with it, intentionally or not. But sometimes the mouthpiece of a generation is most representative when it is yawning.

Rob Horning is an editor at the New Inquiry.