The Epic Battle Over Atlantic Yards

The Epic Battle Over Atlantic Yards

N. Oder: Battle Over Atlantic Yards

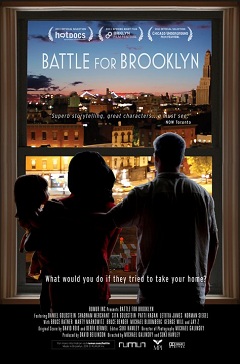

A documentary directed by Michael Galinsky

and Suki Hawley

THE SEVEN-years-and-counting controversy over the $4.9 billion Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn—an arena for the relocated New Jersey Nets and sixteen towers bringing downtown Brooklyn to neighborhood Brooklyn—has bitterly divided Brooklynites and become a national symbol of development run amok.

Supporters of the project include the political establishment and black members of community groups backed by politically wired developer Forest City Ratner (FCR), who embraced the slogan of “Jobs, Housing, and Hoops.” Opponents, most prominently from the gentrified neighborhoods facing encroachment, have pointed to the project’s oversize scale, eminent domain based on bogus “blight,” and sweetheart deals for FCR. Atlantic Yards was announced in 2003 as a fait accompli, then muscled through a murky state oversight process with no input from local elected officials. No wonder Charles Taylor, in the Spring 2008 issue of Dissent, called Atlantic Yards an “epic tale of corruption, cronyism, and obeisance to private interest.”

For now, the promises seem limited to hoops. The Barclays Center arena, due to open in fall 2012, is the only building under construction, adjacent to Brooklyn’s biggest transit hub and partially covering a railyard. Starchitect Frank Gehry had drawn up initial Atlantic Yards designs, helping rehabilitate the developer’s rep for pedestrian architecture, but his flashy model was jettisoned for a smaller, cheaper version.

The project was supposed to take a decade, but has been delayed by an over-optimistic schedule, lawsuits, the economic downturn, and the revision of the plan when Gehry left the project. FCR has successfully renegotiated deals with state agencies since the project was first approved, saving itself tens of millions of dollars. Opposition, led by Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB), crested in 2006 with public protests; after that, DDDB and allies fought uphill in courts that typically defer to government agencies.

The sprawling saga could merit a miniseries; Battle for Brooklyn, the propulsive ninety-three-minute documentary from Michael Galinsky and Suki Hawley—Brooklynites known for the 2002 doc Horns and Halos, about an ill-fated George W. Bush biographer—chooses a narrower lens. With reality show-like intimacy, the film focuses on Daniel Goldstein, a graphic designer turned DDDB spokesman, the sole owner in his condo building to refuse a buyout. We see Goldstein find himself over six years as an activist, alternately invigorated and unnerved. The David-and-Goliath portrait can be compelling, but it avoids some gray areas, and sometimes Goldstein’s personal story displaces needed context. The directors explain that they’ve crafted a film that’s more character driven than information driven. Still, the title suggests some sweep, and the film scants Brooklyn’s gentrification, the reason FCR’s repeated, if questionable, promises of affordable housing have had such heft.

“IF I had to do it all over again, I would do the same exact thing,” Goldstein declares in the film’s opening lines, as a camera-from-the-sky captures the denuded project footprint, with ominous music in the background. “If I wasn’t going to fight this project, which was hitting my home and my neighborhood, what would I ever fight for?”

The film suggests one man’s—or one community’s—struggle against powerful forces. We learn that Goldstein spent five years looking for a home but not how his adversaries stressed he’d been there less than a year when the project was announced. Goldstein’s no storybook plaintiff, unlike Susette Kelo of New London, Connecticut, whose cherished “little pink house” symbolized the country’s most infamous eminent domain case. In fact, Ratner’s willingness to challenge gentrified Brooklyn neighborhoods, relying on working-class proxies of color, is notable. As one activist observed in investigative theater company The Civilians’ 2010 documentary play In the Footprint: The Battle Over Atlantic Yards, “I come from a class where you don’t usually get fucked over in such an obvious way.”

The film suggests one man’s—or one community’s—struggle against powerful forces. We learn that Goldstein spent five years looking for a home but not how his adversaries stressed he’d been there less than a year when the project was announced. Goldstein’s no storybook plaintiff, unlike Susette Kelo of New London, Connecticut, whose cherished “little pink house” symbolized the country’s most infamous eminent domain case. In fact, Ratner’s willingness to challenge gentrified Brooklyn neighborhoods, relying on working-class proxies of color, is notable. As one activist observed in investigative theater company The Civilians’ 2010 documentary play In the Footprint: The Battle Over Atlantic Yards, “I come from a class where you don’t usually get fucked over in such an obvious way.”

Two Atlantic Yards opponents other than Goldstein also get significant screen time. City Council Member Letitia (Tish) James comes off well—a tall, commanding woman who can bridge black Brooklyn and the more yuppie protesters. She can speak in media soundbites (“What we need to do is develop it but not destroy it”) yet also snap, “That shit ain’t real.” Then there’s Patti Hagan, the first resident to raise the alarm. She has been portrayed as a bit of a crank, but here appears as the dogged opponent, rightly disparaging Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz for his fixation on the loss of the Dodgers. In one scene, she gets local business owners to scoff at developer claims that the area “never really took.” Still, Hagan’s statements could use some footnotes; she argues that eminent domain leads to lowball reimbursements for property owners, but that’s not always the case. Some condo owners in the Atlantic Yards footprint seemingly did quite well, but, as the film points out, the payments were accompanied by gag orders, and they were reimbursed with public money.

In addition to In the Footprint, one other Atlantic Yards documentary preceded this one. Isabel Hill’s thirty-minute film Brooklyn Matters (2007) was a strong prosecutorial brief. The Civilians’ play leaned toward the opponents but, more than either film, gave voice to supporters like ACORN’s Bertha Lewis and James Caldwell of BUILD (Brooklyn United for Innovative Local Development). However, neither work conveyed, as Battle for Brooklyn does, the character of the official talking heads backing the project, or the sweeping story: the tension in a courtroom, the energy (sometimes deflated) in a City Council hearing, or the awkward interactions between press and the protagonists.

HAVING OBSERVED much of the story in real time, I found Battle most valuable in the camera’s witness to the palpable insincerity and cold-blooded indifference of the developer-government alliance. Though Atlantic Yards may not directly evoke the Robert Moses era, when massive numbers of people in New York City were displaced by large public projects, the film shows that the powers today are less blatant but still relentless.

Battle pays off with riveting crosscut scenes on the day of the ceremonial arena groundbreaking, March 10, 2010. Goldstein tells an interviewer, “We should not be celebrating it today, we should be investigating it today.” The film toggles to a press conference by opponents; official speakers at the groundbreaking; Goldstein facing lockdown security on the no-longer-public street where he lives; a public protest; and FCR executive Bruce Bender, all smiles.

Yet as with In the Footprint, Battle skews toward the rich early years of the controversy. You’d hardly know that passionate legal advocate Norman Siegel left the fight early on; in one scene, he makes a good case at a City Council meeting that the game was rigged.

But the film does show who’s done the rigging.

Company CEO Bruce Ratner, who bought the Nets to leverage the real estate deal, is the über-developer. Ratner may seem owlishly corporate, but he introduces the somber-faced Reverend Herbert Daughtry, a firebrand black minister who became a supporter, with calibrated politesse: “Reverend Daughtry has agreed to help us think through the issues of housing and jobs.”

Another fixer is Bruce Bender, who claims he’s so excited about the project that “I’m going to jump out of my seat,” then confounds himself in doubletalk, claiming that “people will not be displaced. They’ll be displaced, maybe from this location, but moved to a place where they can be productive, in their jobs.”

New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg also makes a number of appearances. In one, he imperiously dismisses questions about the much-promoted Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), purported to guarantee affordable housing, local hiring, and minority contracting. “I would add something else that’s even more important,” the mayor declares. “You have Bruce Ratner’s word, and that should be enough.” But as Battle shows, the CBA is suspect; indeed, though not depicted, Bloomberg recently disparaged such agreements as “extortion.”

Finally, there is jowly, showman-like Brooklyn Borough President Markowitz, who beams at the project launch, asserting, “Brooklyn is a world-class city that deserves a world-class team.” In an interview, he piles on Brooklyn food metaphors: “This puts the strawberries on a Junior’s cheesecake. This puts the Russian dressing on a great pastrami sandwich at Mill Basin Deli.” Later, at a rally to boost the stalled project, Markowitz appears apoplectic with anger.

We see more of Bloomberg than the state’s parade of governors, or the little-known state officials who bureaucratically wield the power of eminent domain. The camera does capture an Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) board meeting, during which a staffer uncomfortably reads that “a blight study…documents blighted conditions on the project site.” Then a board member, clearly unprepared, casually questions the project location. Interviewed afterward, Goldstein and fellow opponent Hagan shake their heads at the board’s rubber-stamp approval. Later, at a public meeting, an ESDC lawyer phlegmatically explains how the agency kowtows to FCR: “Some have asked why we are considering changes to the project that might be perceived as being beneficial to the developer. Without these changes, the project cannot move forward, and we believe the project will be of great benefit to the city and state.”

The film focuses on eminent domain, the state’s power to take private property for public purpose—a broad definition that, as the 2005 Kelo case reminded us, extends well beyond literal “public use.” The filmmakers do a good job depicting the twenty-two-acre project “footprint” as an inset, with a bulls-eye over Goldstein’s block. In one scene, Goldstein and his attorney explain to visiting conservative columnist George Will that Ratner drew the project map and sought the site not because of blight, but for its strategic value.

We’re fortunate that the New York State Court of Appeals, unlike the state’s lower courts, allows cameras, since the October 2009 oral argument in the state eminent domain case provides an arresting moment in the film: ESDC lawyer Philip Karmel stalls uncomfortably for some six seconds as he’s unable to answer whether the state gerrymandered the project map at FCR’s request. We learn later that Goldstein and fellow petitioners lost the case, 6-1. But we’re not told how the sole dissenting judge cited the map, while the majority simply ignored it—which is why the court’s decision has been widely denounced. Battle’s directors, however, do not point out how eminent domain can make for strange bedfellows, with Brooklyn activists working with the libertarians of the Castle Coalition, or that, given that New York has the country’s most condemnor-friendly eminent domain laws, such an alliance shouldn’t be shocking. (The film is also supported by the libertarian Moving Picture Institute.)

WITH SUCH odds stacked against him, we might ask, what drives Goldstein? Early in the film, at a press conference announcing the formation of DDDB, Goldstein reads a statement awkwardly and nervously, yet tells his interviewer somewhat unwittingly, with a smile, “I think it went really well, and I think I like this.” (He explained to a New York Times interviewer in 2005 that he was a political junkie.) Later, he’s far more polished, speaking fluently and aggressively, wrangling reporters. The film also suggests how Goldstein and others in the homegrown opposition used the new tools of the web in their fight. In one late 2009 scene, as Goldstein waits at his computer for the eminent domain decision to emerge, he toggles between two press releases prepared, one in case of a victory and the other a loss. Goldstein would convert DDDB’s home page into blog format, and many activists relied on various other blogs opposing or critical of the project (like my Atlantic Yards Report).

Goldstein can be a combative sort, but that’s shown onscreen just once, at a City Council meeting. Goldstein resists the time limit, raising his voice to retort, not without justification, that project supporters were given way more time than opponents. The directors choose not to complicate their generally admiring portrait of Goldstein by citing his ill-advised email to a reporter in which he urged investigation of “plundering astroturf groups and their wealthy white masters.” He was right on the larger issue—the developer did claim support from astroturf groups—but his language provoked a brief media fracas and mirrored racially charged statements made by project supporters.

Early in the film, Goldstein portrays FCR’s buyouts, quieting condo owners, as an effort to split the district by color and class lines. Later, he declares, “There is no divide.” Yes, FCR fostered the divide, but once again there’s more to it. DDDB had trouble recruiting working-class people of color—who, understandably, saw it as less of their fight—and the developer managed to do so, though many were from groups that expected direct benefits. It’s not surprising that those living closer to the project would be more concerned about negative consequences, while those farther away focused on benefits.

The film depicts clear racial and class tensions, as a large, gold-toothed black man, ex-con Darnell Canada, warns ominously at a public meeting, “You all oughta be glad that we want to work, because if we don’t work, we’ll do whatever we have to, to survive.” Assemblyman Roger Green—who declares early on that, given the power structure’s support for the project, someone had to enter into a CBA—baits the crowd: “I was born in Brooklyn. I was raised in Brooklyn. I walked these streets before some people got here.” It’s an ugly moment. As for Brooklyn cred, Goldstein counters by pointing to the role of the Cleveland-based Forest City Enterprises, the parent of FCR, and the eventual purchase of the Nets by Russian billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov.

Goldstein himself suggests that his motives were political, not financial. He tells an interviewer that “just because you have the money doesn’t mean you can ram this project down people’s throats.” He also claims, in a soundbite, that “New York State has sanctioned the theft of my home.” However, Goldstein, after losing title to his apartment and getting a lowball offer from the state, settled for $3 million, a number that FCR immediately portrayed as greedy—and the tabloids agreed, somehow forgetting how much the developer had gotten from the public. Given legal fees, taxes, rental and relocation fees, and the cost of a replacement apartment, Goldstein didn’t take home that much, but the $3 million figure doesn’t appear in the film. The filmmakers claim that it would’ve been too complex to explain; while they have a case, it still seems unbalanced by the earlier discussions about money.

THOUGH ABSENT for much of the film, a few talking heads appear toward the end. The New York Times’s Charles Bagli declares, “Here we are, so many years later and you start scratching your head and you say, ‘Well, I see the arena going up, the steel is rising, but I don’t see any housing, the famous architect’s gone,’ it fed the notion that this was a hollow accomplishment.” Bagli implicitly rebukes Mayor Bloomberg’s confident, placating assertion a year earlier at the arena groundbreaking: “Nobody’s going to remember how long it took, they’re only going to look and see that it was done.” The final talking head is my own: “If the government had done its job, if the media had done their job, we wouldn’t be here like this. It would’ve been a fair fight.”

But perhaps the most memorable quote comes from FCR’s Bruce Bender, who points out, not without reason, that people protested but ultimately embraced another large New York development project, Rockefeller Center. “How often can a basketball team, a major league franchise, go from one place to another?” he continues, grinning for the camera. “How often is a new arena going to be built?”

By the end of Battle, we’re left wondering: Are those remotely the right questions?

Disclosure: The filmmakers asked me to view a near-final version of the film and comment on factual errors. I did so, and they made most, though not all, of the changes I recommended. Also, the filmmakers, knowing that I’d write a book on Atlantic Yards—and encouraging it as a more definitive work than they could manage—have given me access to hours of footage they’ve shot. They did so knowing that I wouldn’t pull punches in my review.

Brooklyn journalist Norman Oder, who’s written the watchdog blog Atlantic Yards Report for more than five years, is working on a book about Atlantic Yards.

Photo: Daniel Goldstein’s residential building in the Atlantic Yards footprint (photo and map courtesy of Tracy Collins)