Steady Work: Sixty Years of Dissent

Steady Work: Sixty Years of Dissent

A history of Dissent magazine, by Maurice Isserman.

The purpose of this new magazine is suggested by its name . . . . The accent of Dissent will be radical. Its tradition will be the tradition of democratic socialism. We shall try to reassert the libertarian values of the socialist ideal, and at the same time, to discuss freely and honestly what in the socialist tradition remains alive and what needs to be discarded or modified.

—Irving Howe, 33 years old, Lewis Coser, 40 years old, co-editors, “A Word to Our Readers,” Dissent, January 1954I found Dissent online somehow and read it, and thought, “Wow, these are my politics!” And presented with intellectual sophistication and clarity. I came to the magazine because of its tradition, not in spite of it. The challenge is to take its resources, its ideas and infrastructure, and turn them to urgent contemporary political purposes. We’re socialists, whatever that means now in America, and we draw on Dissent’s history to guide us.

—Sarah Leonard, 25 years old, Dissent associate editor, interviewed in 2013

Volume I, No. 1 of Dissent showed up in mailboxes of charter subscribers in early 1954, as inauspicious an occasion for the debut issue of a socialist magazine in the United States as can be imagined. Republicans controlled both the White House and Congress. Senator Joseph McCarthy and Vice President Richard Nixon were waging a no-holds-barred political war to stigmatize Democratic opponents as soft on communism—or worse. Demoralized and divided, Democrats feebly defended themselves against charges that their party had presided over “twenty years of treason,” while some panicked liberal leaders abandoned any commitment to basic civil liberties.

Over the preceding half-decade, scores of Communist Party (CPUSA) leaders had been sentenced to federal prison, not for espionage or similar crimes against national security (of which some were indeed guilty), but for violating the Smith Act, a law passed in 1940 that made it a crime to conspire to advocate the teaching of the desirability of the overthrow of the U.S. government. The evidence presented against the defendants in those trials consisted largely of lists of books by Karl Marx and V.I. Lenin and other revolutionaries available for sale in party bookstores.

The anti-Stalinist left, including people who read some of the same books for which Communists were being jailed, was organizationally in shambles, with the once proud Socialist Party (SP), founded by Eugene Debs and now led by Norman Thomas, reduced to less than a thousand members. Other anti-Stalinist grouplets, including the Independent Socialist League (ISL), led by Max Shachtman, counted even fewer adherents. Worse yet, many on the anti-Stalinist left were wedded to a sectarian outlook that sociologist and former socialist Daniel Bell accurately described in his 1952 essay “Marxian Socialism in the United States” as rooted in “the illusions of settling the fate of history, the mimetic combat on the plains of destiny, and the vicarious sense of power in demolishing opponents.”

While organized radicalism was at a twentieth-century century nadir, independent radical thought found few outlets for expression. American intellectuals, many of whom had supported one or another radical group in their younger days, now tended to keep their heads down politically, while a few, out of conviction (or opportunism), became open apologists for McCarthyism. Universities purged faculties of left-wing professors, including those who refused to name names before congressional or state legislative investigating committees or to take state-imposed loyalty oaths. There was much talk in intellectual/ academic circles about the virtues of consensus, pluralism, and interest-group politics. Meanwhile, mass political protest was dismissed as either obsolete or the inevitable prelude to totalitarianism, while little was heard about potentially controversial and divisive issues such as poverty or racial discrimination.

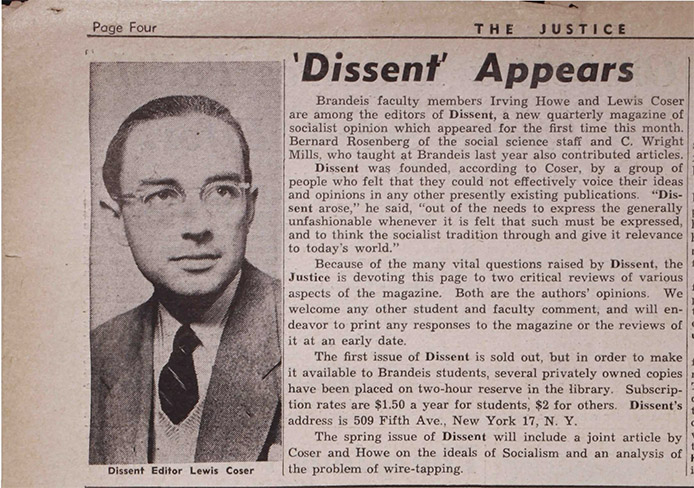

Given the political climate, Irving Howe and Lewis Coser, co-editors of the new magazine, found it easier to explain in that first issue just what it was that Dissent was not proposing to do than what it hoped to accomplish. While reaffirming a commitment to their own vision of democratic socialism, they denied any intent to try to create a “political party or group”:

On the contrary, [Dissent’s] existence is based on an awareness that in America today there is no significant socialist movement and that, in all likelihood, no such movement will appear in the immediate future.

The founders raised about two thousand dollars, enough to guarantee that four issues of Dissent would appear; whether it would make it to Volume II remained an open question. Coser recalled a conversation with Howe on the prospects for their venture in which his co-editor said, “Well, two, three, four issues and then of course we go bankrupt and that will be that, but we will have made a heroic effort.”

Not prone to accentuate the positive (his long-time comrade at the magazine, Bernard Rosenberg, once described him as a man of “infrequent gaiety and usual melancholy”), Howe was for once actually being too pessimistic. Dissent made it to Volume II in 1955. And to Volume XV in 1968. And to Volume XXXVI in 1989. At this writing, it is at Volume VX, sixty years and still chronicling and questioning.

In these pages, the six-decade history of Dissent will unfold, as it were, as a three-act play: Founding, Passing, and Renewal. The first act (longest because it requires some backstory) covers the magazine’s formative years roughly up to 1972, a time of achievement; growth; and, ultimately, an unforeseen and bitter generational conflict. The second act, from the early 1970s through 1993, covers a period of generational reconciliation on the democratic left, as well as the passing of the first generation of Dissentniks, along with the political world that shaped them. The third act, from the 1990s to the present (and stretching into the immediate future), concludes with the emergence of a third generation of younger readers, writers, and editors who are carrying on the steady work of dissent and Dissent.

Act I: The Founding

Some people wondered why we couldn’t be more like the old Masses, the lively radical magazine of the years before the First World War, and all I could mumble in reply was that the old Masses had been published before the bad news arrived.

—Irving Howe, A Margin of Hope

The man who became known as Irving Howe was born Irving Horenstein in New York City in 1920, in then heavily Jewish immigrant East Bronx. His father owned a grocery store, which failed in the early years of the Great Depression. Afterward, both parents worked in the garment industry. His parents’ poverty, and the modest improvements that came to them in time through membership in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), were formative influences in the son’s life. He became a socialist at the precocious age of 14, joining the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL), the youth affiliate of Norman Thomas’s Socialist Party. He graduated at age 16, in 1936, from the DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx (reputed at the time to be the largest high school in the world, with 12,000 students, as well as an incubator for budding radicals) and from the City College of New York (“the Harvard of the Proletariat” to its admirers) at age 20 in 1940. He enrolled in but never completed a graduate program in English literature at Brooklyn College.

His real education came through the socialist movement. In 1936, two years after Howe joined YPSL, the Socialist Party agreed to allow members of the Workers Party (WP) to join its ranks, a fatally misguided decision. The WPers, whose principal leaders were James Cannon and Max Shachtman, were followers of exiled Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Trotskyists saw themselves, rather than the Communists (whom they always referred to as Stalinists), as the legitimate heirs of the Bolshevik revolutionary tradition. As such, they had little regard for, what seemed to them, the tepid milk-and-water reformism of their comrades-of-convenience in the Socialist Party. Not surprisingly, the Trotskyists’ sojourn in the SP proved brief; they were expelled in 1937 for factionalism. But they managed to carry off a large percentage of the party’s youthful left wing into the newly founded Socialist Workers Party (SWP)—among them City College freshman Irving Howe.

Irving Howe upon his graduation from CCNY

Shachtman, sixteen years Howe’s elder, a mesmerizing speaker and hardened faction-fighter, was the leader most admired by the younger Trotskyist recruits. As a newly minted professional revolutionary, Comrade Horenstein adopted a “party name” (a hallowed Bolshevik tradition). At first he went by “Hugh Ivan,” which sounded like a composite of characters from novels by Sir Walter Scott and Isaac Babel, but changed in time to “Irving Howe.” Howe became one of “Max’s boys,” as Shachtman’s protégés were called, and modeled himself on his mentor’s platform presence and mannerisms. Listening to Shachtman, in those heady days when world revolution seemed on the horizon, provided a rigorous if narrow grounding in political theory.

At City College, in contrast, Howe paid little attention to his studies. He was more interested in the debates taking place in the famous “Alcove 1” of the school cafeteria, where the anti-Stalinist students congregated daily (neighboring “Alcove 2” was where the hated Stalinists of the Young Communist League presided). Irving Kristol, another of “Max’s boys,” would later describe the Howe he knew at City College as

a pillar of ideological rectitude. Thin, gangling, intense, always a little distant, his fingers incessantly and nervously twisting a cowlick as he enunciated sharp and authoritative opinions, Irving was the Trotskyist leader and “theoretician.”

From a far friendlier source than Kristol, Howe was described as “quick, smart, impatient. Very impatient with people—he wanted everyone to be as quick as he was.” That source, Lewis Coser, first encountered Howe in 1941. Coser’s path to their initial meeting had been full of twists, turns, and perils. Born in Berlin in 1913 as Ludwig Cohen, the son of a wealthy Jewish banker father and a Protestant mother, he too became involved in socialist politics as a teenager. Coser left Germany for England in 1932 before moving to Paris a few months later.

Interned by French authorities as an enemy alien when the Second World War broke out (notwithstanding his antifascism), he fled France in 1941. In New York, a German-Jewish refugee named Rose Laub had worked on his behalf to provide the necessary paperwork for his admission to the United States. They met after his arrival and were married in 1942. (Laub’s parents had been socialists in Germany, and she was named for their friend Rosa Luxemburg.)

In 1940, following the successive shocks of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, the Red Army’s invasion of eastern Poland, and the Soviet war against Finland, Shachtman and James Burnham, co-editors of the Trotskyist theoretical journal New International, broke with Trotsky and many of their American comrades on the Russian Question. The Soviet Union, they now argued, did not deserve their defense, for it was in no sense of the word truly socialist, “degenerated” or otherwise. In the conflict between the Soviet and capitalist ruling classes, socialists should stand apart from both, in a “third camp.”

Notwithstanding his own deeply engrained sectarian instincts, Shachtman attracted some very bright and talented young people to the groups he led. Alumni of the Workers Party and its successor organizations would go on to play a central role in the history of the American left, and in the larger political world, but never through force of numbers. In the fall of 1940, this latest self-proclaimed vanguard party of the proletariat counted 323 members in good standing, most of them living in New York City.

Prominent among their number was Howe, newly appointed editor of the WP’s weekly newspaper Labor Action. By the time he was drafted into the Army in 1942, Labor Action was printing 40,000 copies a week, making it the largest publication he would ever edit (although most of those copies were handed out for free at factory gates by WP activists).

Although the Party opposed the Second World War as just another an imperialist conflict, it was WP policy for its members to serve in the military if drafted. Howe wound up stationed in Alaska, where he used his time away from the movement to work his way systematically through the classics of European and American literature. The idea of one day being able to teach those books in a university setting had not yet entered his mind, but—courtesy of the U.S. military’s apparent policy of dumping radical GIs in the frozen north to keep them out of trouble—he was laying the groundwork for his subsequent professional career.

Irving Howe (left) in Alaska, early 1940s

After military service, Howe resumed his duties on behalf of the Workers Party, which included writing pamphlets with such bristling titles as “Smash the Profiteers” (1946) and “Don’t Pay More Rent!” (1947). He also confronted the question of how to support himself when his GI Bill benefits ran out. He began to piece together a living as a freelance intellectual, working as an editorial assistant at Dwight Macdonald’s Politics, as well as for Hannah Arendt at Schocken Books.

His first book, The UAW and Walter Reuther, co-authored with union activist B.J. Widick, was published in 1949. By 1952, Howe had written literary biographies on Sherwood Anderson and William Faulkner. Another big step toward a new way of life came in 1953, when he applied for a position teaching English at Brandeis University, where Coser was employed. To his surprise, he got the job, despite a lack of previous teaching experience and any academic credential beyond a B.A. in English.

For all that, Howe was reluctant to break with the comrades of his youth, and remained in the party four more years. In the meantime, the Workers Party changed its name to the Independent Socialist League (ISL), an indication that Shachtman himself was beginning to doubt the appropriateness of the Leninist model of a revolutionary vanguard in the U.S. setting.

But such changes were too limited for Howe. When he and an equally disenchanted comrade, Stanley Plastrik, finally quit the ISL in 1952, they complained in their letter of resignation that the ISL’s “shell of isolation has begun to seem almost comfortable, and what was once felt to be the tragedy of sect life has now covertly become glorified in the psychology of the ‘saving remnant.’”

What to do next? “When intellectuals can do nothing else,” Howe wrote with some apparent self-deprecation on the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of Dissent’s founding, “they start a magazine.” (Howe always insisted that Dissent editors refer to their publication as a “magazine,“ which suggested a commitment to reaching a general audience, as opposed to a “journal,” which implied a more specialized kind of writing and readership.) Actually, as Howe understood, starting such a magazine could have considerable impact in intellectual and academic circles.

In 1953, Howe called a series of meetings to round up supporters for the project. Lew and Rose Coser were early recruits. Coser agreed to be co-editor with Howe, and proposed the name “Dissent.” Stanley Plastrik became business manager, aided and eventually replaced in that role by his wife, Simone, an important behind-the-scenes figure in the magazine’s early history. Emanuel (Manny) Geltman, another former Shachtmanite, as well as former editor of Labor Action, took charge of design, layout, and other aspects of production. Bernard (Bernie) Rosenberg was involved from the start, although he did not show up on the editorial board for another year; another sociologist, Dennis Wrong at Princeton, also took part in the early planning meetings, but did not join the board until a decade later. Frank Marquart, a veteran Detroit socialist and labor educator, was one of the few contributing editors who hailed from outside the Boston-New York-Princeton corridor; he became a frequent and valued contributor on labor issues in the 1950s. Joseph Buttinger, an Austrian refugee, and his wife, Muriel Gardner, a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, people with means as well as socialist sympathies, provided about half the funds necessary to launch the magazine (and much more in years to come). Art critic Meyer Schapiro, psychologist Erich Fromm (another German Jewish refugee), and novelist Norman Mailer lent the prestige of their names to the effort as members of the editorial board or contributing editors.

Dwight Macdonald, whose Politics ceased publication in 1949, lent Howe his old subscription list, although he declined to write for the new magazine. Most of the editors or contributing editors listed in the first issue were socialists, but they included in their number anarchist George Woodcock and pacifist A.J. Muste.

Meyer Schapiro asked New York expressionist artist Gandy Brodie to design the magazine’s logo. He came up with a free-form logo of the magazine’s name that ran at the top, yellow on black, on the cover of the first issue and black and backward at the bottom. The cover color varied by issue, but otherwise the pattern was unvarying: the logo, a list of articles and authors, and that was it.

The same Spartan principles governed the interior design: issues in the 1950s featured page after page of uniform print. Apart from images accompanying paid advertising, it would be decades before a photograph or illustration found its way inside Dissent’s pages. A year’s subscription cost $2.00; a single issue could be purchased for 60 cents at one of the two dozen New York City bookstores that carried it, along with a few other select venues in Chicago; Ann Arbor; San Francisco; and, surprisingly, Hollywood.

Howe later described that first issue of Dissent as a disappointment, “a mixture of academic stuffiness and polemical bristle.” But that seems an overly harsh judgment for an issue that included sociologist C. Wright Mills (never on the editorial board, but a frequent contributor to the magazine in its early years) writing on “The Conservative Mood,” contributing editor George Woodcock writing on the legacy of George Orwell, and Howe himself offering up a brisk and dismissive account of the love affair between American intellectuals and 1952 Democratic presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson.

From the beginning, Howe had exacting standards for the writing in Dissent’s pages, but that did not mean there was a “house style” at the magazine. He rejoiced when writers such as Harold Rosenberg or Lionel Abel or Paul Goodman brought to Dissent their distinctive voices. And, of course, those contributors usually required the lightest of editing, leaving more time for him to help less gifted writers make their points more clearly. Sometimes even accomplished writers turned in clunky prose, and then there were hard choices to be made. Howe once rejected a piece by one of his personal heroes, literary critic Edmund Wilson. Thereafter, Howe reported, “he would chaff me about being turned down by a magazine that didn’t even pay.”

Howe believed any piece of writing could be improved by running through another draft and cutting by 10 percent. As his son, Nicholas, himself a professor of English, suggested some years after his father’s death, “Good prose was never an absolute value in itself, but writing clearly and directly about even the most complex of topics, spoke to a shared value of openness and respect for the reader. There was a vision of politics in such prose.”

In contrast with some earlier examples of little magazines of the left, like Partisan Review, Dissent’s internal history was uneventful. It suffered no momentous upheavals, schisms, or changes in worldview. It scarcely ever missed a deadline. The editors were extremely cautious in their management of the magazine’s affairs. Michael Walzer, who first encountered Howe while an undergraduate at Brandeis in 1953, and who was involved with Dissent from almost the beginning, recalled, “the whole thing was run like a mom-and-pop grocery store.”

Until the end of the twentieth century, there was no Dissent office, just a mail drop and some space in the Plastriks’ apartment, where the subscription lists were kept in a spare bedroom closet. Editorial meetings took place in one or another editor’s living rooms. According to Walzer,

Ours was petty bourgeois radicalism at its best, with a very strong internal ethic of commitment, sacrifice, work . . . . [Y]ou have to find a printer who is politically sympathetic and willing to do the job at a slightly lower rate. To make an arrangement of that sort you’ll have to agree he’ll set your articles in type between other jobs, which means you have to get everything in much earlier. So your lead time is very long, and you have to press writers very hard.

A parable from a Yiddish folktale summarized Dissent’s meaning to Howe. “Once in Chelm, the mythical village of the East European Jews, a man was appointed to sit at the village gate and wait for the coming of the Messiah,” he wrote in the epigraph to a 1966 collection of his political essays:

He complained to the village elders that his pay was too low. “You are right,” they said to him, “the pay is low. But consider: the work is steady.”

He entitled the 1966 collection Steady Work.

Steady work involved many things, including constant vigilance. “Irving was always running the show,” Michael Walzer recalled. “He was always alert to a possible contributor, a possible article.” Despite a combative temperament, he was, surprisingly, the magazine’s peacemaker:

His leadership was intellectual, political, but it was also diplomatic. He was the person who did the necessary stroking and calming. Having lived through many splits Irving was quite determined to hold this group together. Whatever arguments we had with others, we were not going to destroy ourselves.

“The heart of the magazine” in the 1950s, for Howe, “was not its journalistic commentary but its recurrent discussions of the idea of socialism as problem and goal.” Those discussions did not center on this or that reconsideration of Marxist theory. “We didn’t quite know whether we believed in the labor theory of value,” Howe recalled of the early days of Dissent, “but we found it quite possible to live without that.” In the course of the decade most of the editors shed Marxism as a theory, prophesy, or even sentimental attachment to revolutionary change. Nor did they believe any longer in class struggle as a comprehensive explanation of past history, let alone contemporary politics and culture. For Howe and his comrades, socialism had instead become a kind of Kantian categorical imperative, a normative guide to moral duties in the everyday world. Without necessarily believing that one would ever see the dawn of a socialist society, one still needed to live one’s life as a socialist, as if the goal of socialism were a real historical possibility.

Socialism, Howe and Coser wrote in the second issue of Dissent, in an article on utopian thought, “is the name of our desire. And not merely because it is a vision which, for many people around the world, provides moral sustenance, but also in the sense that it is a vision which objectifies and gives urgency to their criticism of the human condition in our time” (emphasis in the original). The utopian vision in Marxism was one that Howe and Coser respected, but wished to amend. Socialism was not to be understood as a secular kingdom of heaven on earth. Rather, they argued, “in an age of curdled realism, it is necessary to assert the utopian image. But this can be done meaningfully only if it is an image of social striving, tension, conflict; an image of a problem-creating and problem-solving society.” Dissent’s socialist project would be to marry a utopian spirit to a non-utopian agenda of immediate and practical reform.

In addition to its reconsideration of the meaning of socialism, Dissent focused attention in its first half decade on a number of pressing contemporary issues, including the Cold War, civil liberties, the fortunes of the labor movement, and, increasingly, civil rights.

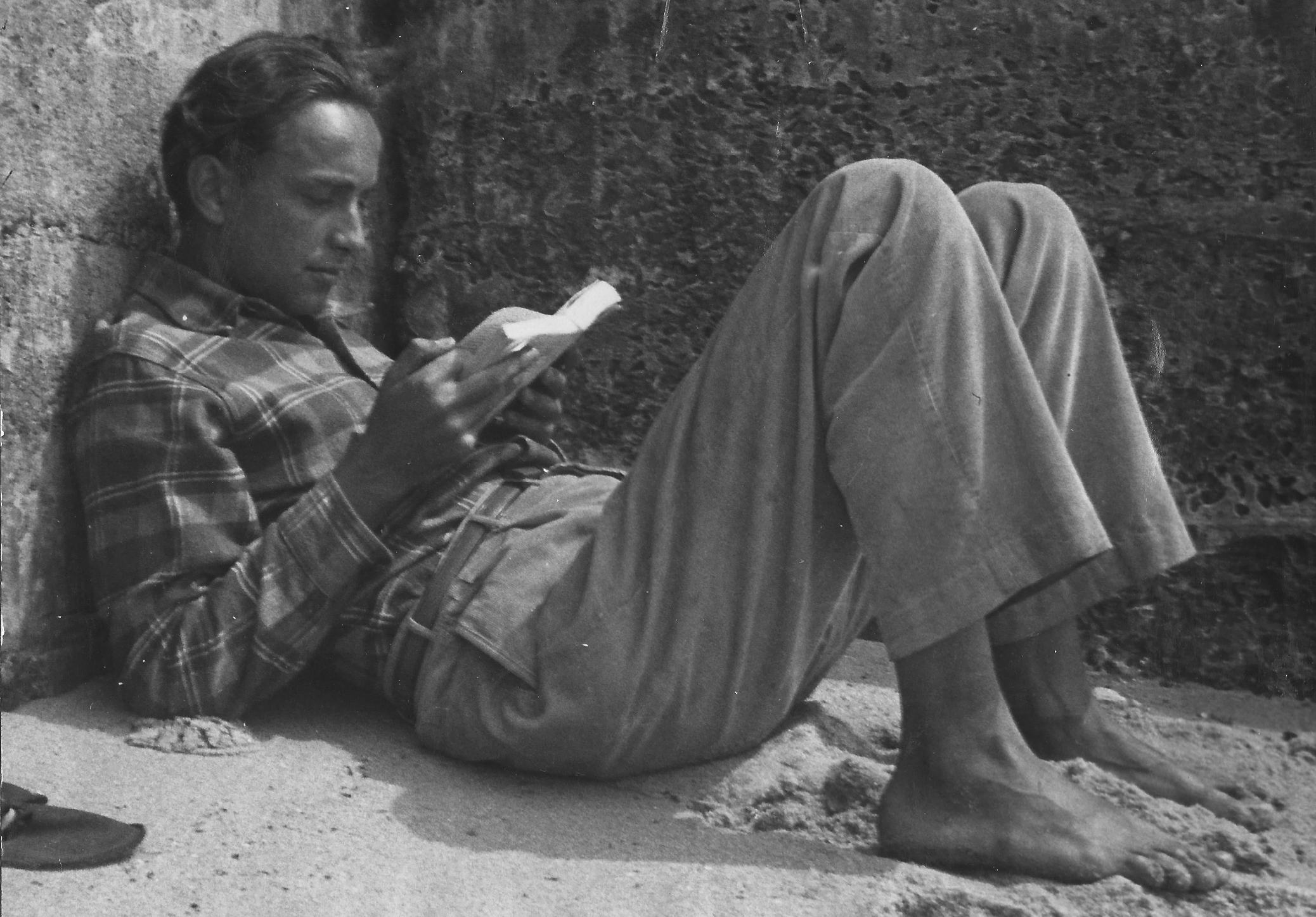

Lewis Coser reading, early 1950s

By 1954, Howe and the ex-Shachtmanites around Dissent had long since abandoned the Shachtmanite “third camp” stance in international relations. There were times when America’s international initiatives had stemmed the spread of Stalinist dictatorship—the Marshall Plan, the Berlin Airlift for example—and they considered that a good thing, and deserving the “critical support” of socialists. But when they disapproved of U.S. foreign policy, they did not hesitate to say so. In the first issue in 1954, Lewis Coser suggested that there were times when the U.S. stance abroad still deserved the label “imperialist,” as for example in Southeast Asia at that very moment. In much of Asia and Africa, Coser suggested, there was no rush to sign up with one or the other superpowers contending for Cold War supremacy. What people sought, and correctly in his view, was the right “to be left alone” (emphasis in the original). If Dissent was no longer in the third camp, it also didn’t feel bound to support every foreign adventure deemed a good idea by U.S. policy makers.

Dissent’s international coverage was heavily weighted toward Europe and included frequent contributions in the 1950s from European exiles living in the United States, such as Horst Brand, a Jewish refugee from Nazism who wrote about the 1953 East German workers’ uprising for the first issue of the magazine, as well as sympathetic European correspondents, such as G.D.H. Cole, who wrote from England the following year about British Labour politics.

Stanley Plastrik played a leading role in coordinating Dissent’s foreign reporting in the 1950s and 1960s, drawing upon a wide range of personal contacts in Europe, India, and Africa. In a 1956 special issue on Africa, edited by Plastrik, George Houser, executive director of the American Committee on Africa and a founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), predicted that a combination of internal resistance and international condemnation would eventually bring an end to the apartheid system in South Africa. To suggest, as many articles in the magazine did in the 1950s, that there were international issues that needed to be viewed outside the context of the Soviet-American confrontation, was indeed to dissent from the conventional wisdom of the era.

Dissent was outspoken in its opposition to McCarthyism, both as practiced by the junior senator from Wisconsin, and, more systematically and even more devastatingly, by the conservative politicians who ran the House Committee on Un-American Activities. But the magazine reserved its greatest scorn for politicians and intellectuals from the liberal wing of American politics who capitulated to McCarthyite hysteria. When Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey introduced the Communist Control Act in 1954 (a bill that made membership in the Communist Party punishable by imprisonment and fines), Howe wrote in disgust in Dissent that “American liberalism [can] never again speak, except with the most vulgar of hypocrisies, in the name of either liberties or liberalism.”

The following year another article criticizing the American Committee for Cultural Freedom appeared in Dissent, this one from a young writer making his first appearance in the magazine’s pages, Michael Harrington. The trouble with the ACCF, Harrington wrote, was that many of its members were infected by the “ex-Communist’ syndrome.” Bearing the scars of years of ideological infighting on the left, they had come to believe that “only they can know the cunning and power of the enemy.” This was not, he concluded, a state of mind “likely to make for either a supple politics or a firm defense of cultural freedom.”

Harrington, 27 years old at the time, was a leader of the latest Shachtmanite youth group, the Young Socialist League (YSL). Harrington would soon be a regular contributor to the magazine, joining the editorial board in 1962, the year he published The Other America. Although separated in age by only eight years, Harrington and Howe represented distinct generations on the left. But they became close political collaborators, and, in their own wary way, good friends.

In interviews in later years, and in his autobiography, Howe suggested it was “silly” that historians had taken to praising Dissent for its courage in opposing McCarthyism: “We had no sense we were taking any great risks in attacking McCarthy.” Dissent editors were in no danger of being dragged from their homes in the middle of the night by the secret police. But that didn’t mean he agreed with those intellectuals who suggested “irrelevantly, that nothing McCarthy did was a bad as what Stalin had done. By that standard, the entirety of American life could be declared immune to criticism, since nothing that anyone, except Hitler, had ever done was as bad as what Stalin had done.”

Even a prominent intellectual with a respectable academic job like Howe was not regarded with benign indifference by the guardians of national security in the McCarthy era. In a 2002 article in Dissent, literary historian John Rodden revealed that Howe had been shadowed by FBI agents in the 1950s. At considerable expense to the taxpayers, and probably marginal benefit to the preservation of the Republic, they monitored his lectures and seminars and intercepted his mail. Howe’s FBI files referred to him as “subject Horenstein,” suggesting that in the opinion of the Bureau, nothing he had done or said since 1940 mattered. To the FBI, the editor of Dissent was still engaged in a revolutionary conspiracy.

If Dissent’s editors were no longer interested in parsing out the labor theory of value, that didn’t mean they had lost their commitment to the labor movement, or more generally, their sense of solidarity with working people. One of the most successful special issues that Dissent published in the course of the 1950s was devoted to “The Workers and Their Unions.” That issue, published in September 1959, sold out completely, and the editors subsequently apologized that they weren’t able to fulfill all the orders that poured in.

The magazine was unique among the intellectual quarterlies of the decade in the continuing and respectful attention it paid to labor issues. That helped it find a small but loyal readership for itself within the leadership of the labor movement, particularly in the United Auto Workers (some educational directors of locals in the union ordered bulk subscriptions for their members). The 1959 special issue included a piece by novelist, journalist, and former Shachtmanite Harvey Swados on unemployed mineworkers in western Pennsylvania. Swados was famous in left-labor circles for his piece in the Nation in 1957 puncturing “The Myth of the Happy Worker.”” The rediscovery of “blue collar blues” by the mainstream media a decade or so later would not come as a surprise to veteran readers of Dissent. The traditionally strong ties with labor were strengthened in the early seventies when UAW education director Brendan Sexton and his wife, sociologist and labor writer Patricia Cayo Sexton, joined the board.

Nor would the rediscovery of poverty, another generally neglected topic in the 1950s. The young journalist Dan Wakefield had an article in that 1959 special issue describing a strike in New York City by hospital workers, largely black and Puerto Rican, organized by the progressive Local 1199. Union pickets caused an uproar by joining a parade of medical students on Fifth Avenue, causing a scuffle with the police. “How messy and disturbing it is,” Wakefield wrote, “when the poor people spoil our parades and demand their own place in the affluent society. . .”

If anything stimulated a “margin of hope” among the soberly pessimistic editors of Dissent in the 1950s, it was the first stirrings of the civil rights movement. In 1956, Lawrence Reddick, a historian at Alabama State College, soon to be one of the founders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), wrote that Montgomery, Alabama, had suddenly “become one of the world’s most interesting cities.” The bus boycott of 1955-56 in that city, led by Martin Luther King, Jr., provided “a magnificent case study of the circumstances under which the philosophy of Thoreau and Gandhi can triumph.” Howe predicted in the same issue that in the future the events in Montgomery would be “looked upon as a political and social innovation of a magnitude approaching the first sit-down strikes in the 1930s.”

No consideration of Dissent in the 1950s would be complete without mention of the most famous article to appear in its pages in that decade, (or perhaps any decade)—Norman Mailer’s “The White Negro,” which ran in the Summer 1957 issue. That was the same year that Jack Kerouac’s On the Road appeared, and a year and a half after Allen Ginsberg gave his first public reading of “Howl.” There is no mention of the Beats in Dissent in the 1950s, either as a literary or a cultural phenomenon. Most of the New York Intellectual literary critics found the poets and novelists associated with the movement incoherent at best, and dangerous at worst.

But, as it turned out, the Beats had a mole on Dissent’s editorial board. Mailer’s sensitive cultural antennae had picked up a shift in the zeitgeist, signaled to him by the rise of the “hipster,” (a term he used interchangeably with “existentialist,” and “beat”). The emergence of “hip,” that is of young, white cultural rebels profoundly influenced by black urban culture, meant to Mailer that “A time of violence, new hysteria, confusion and rebellion” would shortly “replace the time of conformity.” Not a bad prophecy.

The article drew considerable attention outside the usual circle of the magazine’s readers and helped boost circulation. But it contained one line that the editors later regretted, where Mailer seemed to celebrate the “courage” displayed by “two strong eighteen-year-old hoodlums” in beating “in the brains of a candy store owner.” Thinking back a quarter- century later on the decision to publish the piece, Howe confessed,

After you’ve edited 25 pieces by sociologists who can’t write English and you get in a piece like “The White Negro” which is full of bounce and brilliance—and I was probably the first person to read it—this sensational piece which he contributes for nothing, for which he could have gotten thousands of bucks even then, and it helps liven and sell the magazine and get it around, it would have taken a lot of strength and character to get fussy with him. I was probably afraid he’d say, “Well, screw you, I’ll sell it to Esquire.”

Beatniks and Dissentniks, Mailer aside, were rebels whose paths were not destined to cross, probably to their mutual loss. “The White Negro” proved the exception in Dissent’s cultural criticism—which, over the years, skewed radical, but rarely transgressive.1

By the late 1950s, the political prospects for the left began to seem far more promising than they had in Dissent’s early days. Howe decided that it was time for Dissent to rethink its original mission. “Five years ago we felt beleaguered,” he wrote in the Winter 1959 issue of Dissent,

now there is no reason to. We began by being suspicious of “programs,” in the sense of pre-fabricated ideologies advanced by left-wing sects; we should continue to remain indifferent to these, but let us also realize that when young people today ask about our “program” they mean something else . . . . Our first five years were devoted to cleaning up a little [of] our own intellectual heritage; let the next five years be devoted, in part, to seeing what we can say usefully about American society. . .

The times, as the saying went, were a-changin’. One early sign of the changes came in the spring of 1960 when the parsimonious editors of Dissent, in a decision without precedent at the magazine, dispatched the youngest member of the editorial board, Michael Walzer, on an assignment to cover the sit-in movement that began in Greensboro, North Carolina, and spontaneously spread across the South. Walzer’s subsequent article in the Spring 1960 issue of Dissent, included firsthand reporting from Durham and Raleigh, North Carolina, and an upbeat political analysis. “It’s not entirely fair to call the movement spontaneous,” Walzer noted. “’In a way,’ one student said, ‘we have been planning it all our lives’” (emphasis in original). Walzer concluded that for too many years formerly radical intellectuals had viewed politics through “an apocalyptic haze,” in which “every spark of enthusiasm in their hearts and every utopian dream in their heads” was put aside for fear they would prepare the way for the rise of the dark passions of Stalinism or fascism. But the sit-in movement launched by black students, without any prompting or control by their elders, proved it was possible to “step outside the realm of conventional politics” in defense of democratic rights and values. Veterans of the sit-in movement met the following October to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which played a central role in civil rights protests from the Freedom Rides of 1961 through the Selma voting rights campaign of 1965. SNCC’s style of grassroots activism would have a profound impact on the white New Left, particularly the campus activists who joined Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) over the next few years.

Michael Walzer, shown here on Cape Cod, where Howe and the Cosers held planning meetings, was sent to North Carolina to report on civil rights.

Dissent’s editors had been hoping for something like the New Left to emerge for years. Walzer was the magazine’s point man for contact with the emerging movement. In the introduction to a symposium on “young radicals” in 1962, he praised the “desire for personal encounter, the organizational naivete” of the New Left: “The false sophistication and largely vicarious weariness of the fifties is gone, while the surrender of self to history or party, which so often characterized the men of the thirties, has not reappeared.”

The reawakening of energies on the left brought new subscribers to Dissent. No circulation figures were given in the 1950s, and figures for subscriptions and other sales were lumped together between 1960 and 1962. But starting in 1963, the circulation figures were broken out into separate categories, including subscriptions, newsstand sales, free copies, and so forth. In 1963, subscriptions totaled 2,236. In 1964 they reached 2,250 and in 1965, 2,750. By 1966, when Dissent switched to bi-monthly publication, they stood at 3,100. And by 1969, subscriptions reached 4,478. Thus, in the 1960s, the magazine experienced steady if not spectacular growth—an increase in readership that, had it come in the 1950s, would have been heartening.

However, this was an era when even the spectacular seemed to be within reach. Consider the trajectory of another little magazine in the same years. In 1962, Ramparts magazine was a Catholic literary quarterly with a circulation comparable to Dissent’s. By the mid-1960s, Ramparts had transformed itself into a slick New Left monthly that by decade’s end had nearly 300,000 subscribers. Dissent’s editors had no intention of becoming Ramparts (which they despised, out of disapproval of both its politics and the profligate spending habits of its editor, Warren Hinckle). What still requires explanation is why, when left-wing movements and publications of a variety of persuasions were growing so rapidly, Dissent’s subscription numbers hovered in the vicinity of 1.5 percent of Ramparts’.

Part of the explanation is that Howe, who in the early 1960s was no less enthusiastic about the emerging New Left than his colleague Walzer, found it difficult to sound as though that were the case. He cultivated a kind of curmudgeonly persona, probably related to his shyness, that made it difficult for him to convey goodwill to young and unknown political novices.2 Moreover, in his own younger days in the movement, back in CCNY’s Alcove 1, he’d been accustomed to paying his friends the compliment of a rigorous political bashing if they strayed, however briefly, from the correct line to which he adhered. Something like that was at work when Howe and Coser complained in Dissent in the fall of 1961, in an article entitled “New Styles in Fellow-Traveling,” that New Leftists had a tendency to go soft on Stalinism when encountering it in the guise of third world revolutions, in Cuba and elsewhere. Moreover, they charged, young radicals seemed to be “singularly, even willfully uninterested in what happened before the Second World War.”

For Howe and Coser that challenge was the equivalent of a conversational gambit meant to say, “You’re interesting, let’s talk.” To younger radicals, it sounded like something altogether different. Howe and Coser seemed genuinely taken aback when they received an indignant letter from one young woman who doubted that the political inclinations of her generation would “throw very many into the arms of the Communist Party.” In response, the editors conceded that the title of their article was “perhaps ill-chosen.”

Michael Harrington, who befriended Tom Hayden in 1960 in Los Angeles on a civil rights picket line outside the Democratic National Convention, recognized SDS’s importance in the emerging New Left, and hoped to win its leaders over to his own democratic socialist views. In a 1962 Dissent article, Harrington warned unnamed “veterans of the radical movement” (read: Howe and Coser) not to over-react when they heard New Leftists espousing naively positive appraisals of Castro’s Cuba or the like. Although such misconceptions “must be faced and changed,” Harrington warned, the young would not be persuaded by adult edict alone:

As it turned out, neither Harrington nor Howe would move the New Left away from “bad theories.” At the Port Huron conference in June 1962, Harrington was in a famously quarrelsome mood. To his subsequent regret, he wound up alienating the young SDSers by demanding that their founding statement include a letter-perfect condemnation of Stalinist perfidy. The following year, Howe invited a group of SDS leaders, including Tom Hayden, Paul Booth, Paul Potter, and Todd Gitlin, to a meeting of the Dissent editorial board. That did not go well, either.

Todd Gitlin (second from right) and I.F. Stone (left), March on Washington Against Nuclear Tests and the Arms Race, February 16, 1952

Gitlin recalled that at the meeting’s end Joseph Buttinger presented him with a copy of his memoir, In the Twilight of Socialism, which Gitlin later came to think “an extraordinary book.” But not that night. “I remember Tom and I looking at each other knowingly, as if to say, ‘Well, for these guys it’s twilight, but we know better.’” Hayden would contribute several articles on the student movement to Dissent over the next few years, but he and Howe were locked into an increasingly bitter antagonism in which each personified for the other the political shortcomings of a generation. Hayden’s name was never mentioned in Howe’s famous polemic critiquing the New Left, “New Styles in ‘Leftism,’” which ran in the Summer 1965 issue of Dissent, but it wasn’t hard to spot him, with a target on his chest, lurking in the article’s margins.

“What you need to see about Dissent’s reaction to the New Left,” Walzer commented decades later, was that the movement “was something long hoped for and worked for and when it came it came in forms that were sometimes quite wonderful, as in the early civil rights movement, and then progressively more and more difficult for us to connect with.”

The escalation of the Vietnam War in mid-decade made it all the more difficult to close the gap. The magazine had a long and honorable tradition of skepticism regarding the benefits of American intervention in Southeast Asian affairs, stretching back to its debut issue in 1954.3 The editors criticized President Lyndon Johnson’s escalation of the war in 1965. But they couldn’t quite bring themselves to call for immediate U.S. withdrawal from the region, which had become the central demand of the growing antiwar movement, because to do so would hand South Vietnam over to communist control.

In 1965, Walzer, closer to the mood on campuses, came out in favor of immediate withdrawal, but Howe and Coser (along with Harrington) called instead for “negotiations.” And that, to youthful antiwar protesters, sounded like a formula for continuing the killing indefinitely. It was only after the Tet Offensive in 1968, which finally tilted public opinion against the war, that Howe came around to supporting the demand for immediate withdrawal.

What if Howe had adopted that position three years earlier, and Dissent had emerged, circa 1965, as a leader in setting tone and strategy for the antiwar movement? At SDS’s first anti-Vietnam protest in Washington in April 1965, the men tended to wear sports coats and ties, the women dresses or skirts; no Vietcong flags were on display, no chants celebrating Ho Chi Minh were heard. Where were Dissent’s editors that day? What if Howe and others had chosen to be arrested at the famous Pentagon protest with fellow editorial board member Norman Mailer in October 1967? Or, what if Mailer had decided to publish his subsequent account of the protest, “The Steps of the Pentagon,” in the pages of Dissent, rather than Harper’s?

What is certain is that the war damaged the magazine. The late Marshall Berman, then a graduate student in philosophy at Harvard, contributed his first article to Dissent in 1965. His next would not appear until 1978. He remembered that by the later 1960s “Dissent seemed to care more about somebody flying a Vietcong flag at a mass antiwar demonstration than about what American guns and bombs were actually doing to Vietnam.” It was only a chance encounter with Howe on a New York City street corner in the late 1970s that led to an invitation to write again for the magazine—and subsequently to Berman’s membership on the editorial board. His untimely death in the early fall of 2013 marked the beginning of the passing of the next generation.

Graduate student Marshall Berman, shown here at Harvard in 1968, was alienated by the editors’ positions on the Vietnam War.

There was a larger problem too—a persistent, almost willed, disconnect with new and unfamiliar trends in culture and politics emerging in the 1960s. For all the magazine’s cosmopolitan sophistication, there was also something parochial in its outlook. The editorial board and list of contributing editors went virtually unchanged from 1960 to 1970. These editors knew what they knew and knew it well (labor, civil liberties, civil rights, economic justice, the ins-and-outs of left-wing, twentieth-century history), but there was a lot they didn’t know, and weren’t particularly interested in enough to find out about.

One looks in vain in the pages of the magazine, for example, for a review of Eleanor Flexner’s The Century of Struggle: The Women’s Rights Movement in the United States (1959), or Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), or Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), or Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963). The topics of those books, from environmentalism to feminism (with the exception of urban renewal), weren’t on Dissent’s radar screen—and the fact that they were all written by women probably wasn’t irrelevant to their being overlooked by what was still, as it had always been, an all-male editorial board.

One new topic did appear on Dissent’s pages in the course of the 1960s, and that was the State of Israel. Although Dissent was often a forum for the discussion of other issues bearing on Jewish life, including a furious controversy involving Hannah Arendt’s 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem, in its first dozen years of existence, the magazine maintained a deliberate silence about Israel—despite the fact that the country was governed by the Labor Party, an affiliate of the Socialist International.

The few references to Israel that did appear in the magazine were not flattering. In an article following the Suez crisis of 1956, Stanley Diamond, a Brandeis anthropologist who had done ethnographic fieldwork on a kibbutz, wrote that “Israel considers itself a beacon of civilization in a benighted area in much the same way that early American settlers viewed the Indians” and went on to predict that “an undercurrent of expansionism in Israel” might come to the fore in its politics.

Henry Pachter, late 1970s

The Six Day War in June 1967 marked a dividing line for the magazine, and for Howe personally. “[W]ho could suppress a thrill of gratification,” he asked in his autobiography, “that after centuries of helplessness Jews had defeated enemies with the weapons those enemies claimed as their own?” (There was one dissenter from that view on the editorial board post-1967, the German-Jewish refuge Henry Pachter, who complained in the July-August 1967 issue about the “wave of mistaken chauvinism” that he saw among Jewish friends celebrating Israel’s military triumph, probably including Howe in that category.) In any case, after the war, Israel became a frequent topic in the magazine’s pages, and Israeli writers such as Amos Oz, Shlomo Avineri, U.S.-Israeli citizen Bernard Avishai, and others became contributors. Dissent’s editors and contributors were often unsparing in their criticism of Israel, especially so regarding occupation policies in the West Bank, but it was also clear that such criticisms were offered from a stance of loyal opposition, based on a commitment to Israel’s existence and security.

Looking back at many of the specific issues that divided Dissent from the New Left, Howe and his colleagues were, more often than not, vindicated. Revolution was neither a realistic nor a desirable prospect in the United States; the university was not simply a cog in the war machine; neither Cuba nor North Vietnam were attractive models of socialism; a strategy, or even a rhetoric, of violent confrontation was self-defeating, and likely to lead to tragedy.

Michael Walzer, the editor of Dissent who had been closest to the New Left in its early days, provided an appropriate epitaph for the movement in the Spring 1972 issue of the magazine, a task in which he took no satisfaction:

There are signs today of a massive withdrawal from political involvement, a spreading mood of cynicism about the possibilities of political success. It is clear that any sort of sustained leftist activity is going to be extremely difficult. In the New Left fall/We suffered all. [Emphasis in the original]

Act II: The Passing

I can’t recall a time when it was as easy as it is today to glance at the headlines of the morning newspaper, and turn quickly to the sports page.

—Michael Walzer, Dissent, Fall 1980

To have lived to the time when Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is published in the Soviet Union, when people there write about Koestler’s Darkness at Noon—you think, maybe the struggle of the anti-Stalinist left wasn’t wasted, after all

—Irving Howe, on the thirty-fifth anniversary of the founding of Dissent, Spring 1989

In 1972, Dissent reverted to its quarterly publication schedule, a great relief to its overworked volunteer editors. As the left-wing movements and sentiments of the previous decade subsided, Dissent lost some subscribers, falling to 3,523 in 1979—about where it had been in the mid-1960s. But there were reasons to think that the downturn in the fortunes of the left, as well as the magazine, were only temporary, and that better times were coming.

The 1970s began with Richard Nixon in the White House, followed shortly by his smashing re-election victory over Democratic challenger George McGovern—but that was followed in turn by the swift unraveling of his administration in the Watergate crisis. When Nixon was forced to resign in August 1974, Irving Howe wrote in the Fall issue of Dissent that when “one remembers the blood that accompanies political successions in other countries, there was something impressive about the recent American events.”

In November of that year, Democrats made strong gains in the midterm congressional elections, and seemed well positioned to regain control of the White House in 1976—good omens for those concerned with protecting the welfare state from further chipping. Perhaps, it was tempting to believe, the Nixon presidency, like Eisenhower’s, would prove an aberration from the normal condition of American politics, in which Democrats controlled the White House and the Congress.

The 1970s also began with a wave of labor militancy, another good thing from Dissent’s perspective. More American workers went on strike in 1970 than at any time since 1946. In the midst of the strike wave, which included a wildcat strike by U.S. postal workers, as well as an authorized UAW strike at General Motors, Time magazine commented, “Blue collar workers are gaining a renewed sense of identity, of collective power and class that used to be called solidarity.”

Of course, what made all this labor militancy possible was that workers, certainly white male workers in unionized manufacturing jobs, had never had it better, at least in terms of their weekly paycheck. In 1970, the United States still enjoyed close to full employment. From the late 1940s to the early 1970s, real hourly earnings of production workers increased an average of over 2 percent per year. As historian Jefferson Cowie (an occasional contributor to Dissent) wrote in his 2012 history Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, “1972 was the apex of earnings for male workers.” Strong unions and a confident working class would, if they proved durable, provide a good social basis for the revival of progressive politics in the 1970s.

Another reassuring factor was that the Republican Party of the early 1970s was not yet fully committed to an all-out assault on the New Deal and its legacy. Ronald Reagan was serving out his final term as governor of California, and although he had presidential aspirations, the memory of ultra-conservative Barry Goldwater’s spectacular defeat ten years earlier did not recommend him highly to many in his own party’s establishment. Economist Robert Lekachman published an article to the January 1975 Dissent entitled “Is the System Finished?” (his answer: probably not), which suggested how, even under Republican presidents in that era, a measure of economic common sense tended to prevail:

The disasters of 1929 and after were unexpected. Our lords and masters have learned something from experience, notably the necessity of government intervention to protect the victims of economic dislocation. No modern democratic government can abandon its citizens entirely to the adversities of either inflation or unemployment. President Ford’s initial tentative stab at an economic program in October consisted mostly of benefits to business, but it also included gestures, which almost certainly will be enlarged into substantial measures, in the direction of public job creation and tax relief for low-income earners.

Still another piece of good news for Dissent was that Michael Harrington was no longer weighed down by the political albatross of his Shachtmanite comrades in the Socialist Party. In the course of the 1960s, Shachtman and his closest lieutenants shifted sharply rightward in political perspective, becoming covert supporters of the war in Vietnam and, by 1972, more or less open supporters of Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign. Such associations hindered Harrington’s attempts to broaden the appeal of the SP, which, alone among the rival parties on the left in the later 1960s (Communist, Trotskyist, Maoist), failed to attract significant numbers of new members. 4

Following Norman Thomas’s death in 1968, Harrington had become chairman of the Socialist Party, but his role was strictly as a figurehead. Although Shachtman died in November 1972, his supporters continued to control the SP, which they renamed Social Democrats, USA.

Like Howe a generation earlier, Harrington was reluctant to break with the comrades of his youth, but when he finally did so, in 1972, new possibilities for the organizational revival of democratic socialism in the United States opened up. Early the next year he presided over the creation of the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC). Howe was among the founding members, the first time since 1952 that he had paid dues to a socialist organization. DSOC, and its successor organization Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), founded in 1982 out of the merger of DSOC and the New Left-influenced New American Movement (NAM), became the largest democratic socialist group in the United States. Dissent remained, as it had always been, an independent socialist publication without formal political affiliation, but DSOC/DSA represented a source of readers, writers, staff, and editors for the magazine in years to come (among the staff members to come from DSOC was Dissent’s long-time managing editor (and later executive editor) Maxine Phillips, as well as book review editor Mark Levinson and editorial board member Jo-Ann Mort, who brought in novelist Brian Morton first as staff and later as a board member.

As Howe moved into his fifties in the 1970s, the question of generational succession at Dissent was much on his mind. He asked Walzer to join him as co-editor of the magazine in 1975. And he made a determined effort to bring in younger writers and editors. If the editorial board as of 1970 bore a strong resemblance to that of 1960, that was much less the case by 1980.

Edith Tarcov, two years before she retired from Dissent

For one thing, women appeared on the editorial masthead for the first time. Patricia Cayo Sexton joined the list of editorial board members in the Spring of 1972, while Edith Tarcov, a prolific writer of children’s books (including a re-telling of “Rumpelstiltskin” that was illustrated by Edward Gorey) and editor of The Portable Saul Bellow, who had been listed as “editorial assistant” since 1966 (and who as such oversaw much of the practical work of getting the magazine published), was promoted to “managing editor” in the same issue. Rose Laub Coser and Deborah Meier were added in the Winter 1974 issue and Cynthia Fuchs Epstein in Winter 1978. Thereafter their numbers slowly but steadily increased (in Fall 2013, women accounted for eleven of the twenty-eight names on the editorial board). Dissent began paying attention to women’s issues and the women’s movement for the first time, and in doing so began a process of broadening its definition of the left beyond the categories (labor, blacks, students, anti-war protesters) it had traditionally recognized as important.

One of the difficulties Howe faced in recruiting new editors and writers to the magazine was that the changing nature of American intellectual life in the years since Dissent’s founding. In an influential jeremiad published in 1987, The Last Intellectuals (a book carrying a pre-publication blurb from Howe), Russell Jacoby lamented the decline of the public intellectual:

The generation born around 1920—Alfred Kazin (1915- ), Daniel Bell (1919- ), Irving Howe (1920- )—might be called transitional. They grew up writing for small magazines when universities remained marginal; this experience informed their style—elegant and accessible essays directed toward the wider intellectual community.

All three of Jacoby’s examples would find academic positions in the 1950s, but two of them never earned PhDs, and Bell’s PhD was awarded for his collection of essays, The End of Ideology, rather than for a traditional dissertation. In contrast, Jacoby argued, the intellectuals born around 1940 (and subsequent generations), found their natural home in the universities, their most important writing centered on completing a dissertation, their training focused on narrow specialties. As a result, “the occasion to master a public prose did not arise” in their careers, and as a further result “to the larger public they are invisible.”

According to Walzer there were “a whole group of people, many of them students of mine,” who wrote for Dissent in the 1970s—but only once:

They had an idea, an experience, a spin-off from their dissertation, and then never wrote again . . . . Academic life welcomed them. The place was wide open.

As the animosities of the 1960s faded in memory, some veterans of the New Left, academics or not, found their way to the magazine. Todd Gitlin, who had been present at the non-meeting of the minds of SDS leaders and Dissent board members in 1963, began writing again for Dissent in the early 1980s, and joined the editorial board in 1989. Joanne Barkan, a self-described “immigrant to Dissent-land from the shores of the New Left,” met Howe in 1979 at the start of the merger talks between the New American Movement and the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee that led to the founding of Democratic Socialists of America in 1982. In 1985, she attended her first Dissent board meeting as a guest:

How did the Dissent board look to a person of NAM descent? Pretty old, very male, professionally homogenous (many academics) and politically heterogeneous (socialists, social-democrats, liberals, a few heading farther to the right.)

At the same time, there were some things about the group that had come to seem preferable to her own political tradition: “I sensed less alienation from American society, less anger.” There were still differences to be overcome before she stopped feeling like an outsider:

Someone asked how the magazine could increase the number of women writers. “Just set yourself a goal for every issue, I piped up, “for example, one third women.” Howe looked grim. Someone else called out, “Do you mean affirmative action?” I clearly didn’t know the native lingo.

Barkan eventually learned the lingo (while helping to change it), even became friends with a not-so-grim-as-he-seemed Howe, and joined the editorial board in 1989.

One final recruit from a 1960s background is worth mentioning. Michael Kazin, a new professor of history at Georgetown University, got his start in left-wing journalism writing for the New York City-based Liberation News Service, the New Left equivalent of the Associated Press, as well as a local underground newspaper in Portland, Oregon, The Willamette Bridge. He contributed his first article to Dissent in 1990, and joined the editorial board in 2000.

Meanwhile, back in the mid-1970s, Dissent editors and writers were increasingly dismayed by the steady accumulation of bad economic news confronting Americans. The 1973 OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) oil embargo had come and gone, leaving higher energy prices in its wake. More disturbing were the ongoing systemic problems of inflation and high unemployment. Manufacturing jobs disappeared, heading south or overseas, never to return. As unemployment mounted, reaching 8.5 percent by 1975, the labor movement began suffering staggering declines: between 1970 and 1982 the AFL-CIO lost more than four million members. The quarter-century following the Second World War, during which government intervention in the economy, a progressive tax system, and an expanding social welfare safety net, plus a high rate of unionization, had made the United States, as Harold Meyerson wrote in Dissent in 1993, the “first nation in history to produce a majority middle class.” In those years, it seemed as if the nation had achieved a permanent prosperity. But in the 1970s that time was coming to an end.

The economic crisis had political and policy consequences that were already being felt in the early 1970s. Hard times did not increase the nation’s compassion for its most vulnerable members—quite the opposite. Michael Harrington’s 1973 article, “The Welfare State and its Neo-conservative Critics,” represented a spirited defense of the increasingly beleaguered War on Poverty. (The question of whether or not Harrington actually coined the phrase “neoconservative” in the pages of Dissent is a vexed one, but it is certainly the case that he popularized its usage.) The neoconservatives, including once liberal or left-wing policy-oriented intellectuals, such as Irving Kristol and Nathan Glazer, had developed an increasingly influential argument that government spending on social welfare programs intended to reduce poverty had the opposite effect, creating a culture of dependency among the poor.

For Harrington, that was nonsense. As he pointed out, the overwhelming proportion of increased federal spending on social welfare from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s, was on programs that benefited the middle class as well as the poor—chiefly Social Security and Medicare. The problem was that the War on Poverty had been over-sold and underfinanced even at its height in the 1960s, meaning, as Harrington concluded, that the “failures of the welfare state . . . are the result of its conservatism not its excessive liberalism or, more preposterously, of its radicalism.”

The Democrats did manage to win in 1976, electing Jimmy Carter to the White House. (Carter did not stir much enthusiasm among the electorate, and even less among Dissent’s editors—although many dutifully voted for him.) Michael Walzer struck an optimistic note in the Winter 1977 issue of Dissent: “Carter himself may or may not have a mandate, but the Democratic party clearly does have one. It is, above all, a mandate for economic reform, and the critical test of the new Administration . . . will come in the areas of employment, taxation, and welfare. Here is where the fight begins, and it will be first of all a fight among Democrats, inside the old New Deal coalition.”

But as it turned out, on employment, taxation, and welfare, “the old New Deal coalition” was no longer able to call the shots. By the time the Carter administration was a year old, Howe was complaining that it “has thus far been decidedly conservative and timid, caught up with the old shibboleths of a balanced budget.” Post-Vietnam, post-Watergate, and suffering from job losses and inflation (“stagflation” as it was called at the time), Americans were increasingly skeptical of the good intentions and effectiveness of government at all levels.

One early and significant expression of that disenchantment came with the passage of Proposition 13 in a California state referendum, which set sharp limits in increases in property taxes. It was a vote with implications for national as well as state politics and policies, as Harold Meyerson argued in his first article for Dissent in Fall 1978:

The main casualty of Proposition 13 within California—and perhaps without—is the dominant politics of the last 40 years. Welfare-state liberalism has almost vanished from the state’s political spectrum. The welfare state itself still limps along, more feebly than before, but without benefit of audible defense. In this state of sects and movements, it doesn’t even rate a cult.

And then things got really bad. Irving Howe’s lead article in the Winter 1981 issue of Dissent was entitled, “How It Feels to Be Hit by a Truck,” the truck being the onrushing conservative wave that in the 1980 election had swept Ronald Reagan into the White House. Republicans were no longer simply “chipping away” at the welfare state; they were hell-bent on its abolition. Two years into the Reagan Revolution, Howe wrote in the Winter 1983 issue of Dissent:

We oppose Reaganism not just on concrete socioeconomic grounds, nor because we believe it won’t “work”—in some sense, it may “work” only too well. We oppose Reaganism because we find its vision of life nasty and brutish . . . The world view of the new conservatism is that of a conglomerate of Captain Ahabs rushing blindly to destruction in pursuit of a White Whale of power and profit.

Simone Plastrik and Maxine Phillips, c. 1980s

The New Deal order was passing. And so, beginning in the 1980s, was Dissent’s founding generation. Henry Pachter and Stanley Plastrik were among the first to go, dying in 1980 and 1981, respectively. Michael Harrington died tragically young in 1989. Howe’s “A Word of Farewell” to Harrington opened the Fall 1989 issue of the magazine. He estimated that he had heard Harrington give speeches in public a hundred times or more,

but I never tired, even when I could guess what would follow: the three points, the slightly ironic turn, the mildly yet really good-natured polemical twist, the ringing call to hope. I never tired because I knew that this was a deeply serious and thoughtful man, but still more, a really good man in whom humane values and fellow-feeling for all who suffered were vibrantly alive.

There was another event in 1989, another passing, more cheering to Dissentniks. That was the fall of the Berlin Wall, followed over the next two years by the dismantling of the Soviet empire and state. “Nothing in our past thinking,” Howe confessed in Spring 1990, “or in anyone else’s, prepared us for the remarkable turn of events in the Soviet Union. So much the worse for theory, so much better for life!” In the same issue, Michael Walzer wrote that it was as if the national democratic revolutions of 1848 were finally coming to fruition in 1990:

The new freedom, if it hasn’t yet produced a coherent politics, has opened up space for opposition newspapers and journals, civic and religious associations, trade union organization, sharp and exhilarating public debate—the recreation of civil society.

Whatever the future was to bring, it was, to borrow from a famous campaign ad on a different topic, “morning again” in Russia and throughout Eastern Europe.

Howe himself had less than four more years to live, dying of an aortic aneurism on May 5, 1993. Michael Walzer opened the Summer issue of Dissent with some thoughts on his legacy:

He never looked for disciples, only for friends and comrades—because he was a man of the left and a committed democrat. I doubt that he possessed the common touch, but he had the necessary negatives: an absolute absence of pretension and arrogance, a deep dislike for political vanguards and ideological gurus. He never aspired to stand at the head of a party or sect, only in the center of a loose circle of people, like-minded enough to argue and worry together.

Over the next decade, most of the original circle of Dissent editors and behind-the-scenes activists died, including Jack Rader in 1991, Rose Laub Coser in 1994, Manny Geltman in 1995, Bernie Rosenberg in 1996, Meyer Schapiro in 1996, Simone Plastrik in 1999, and Lewis Coser in 2003. As arguers and worriers, they were in a league all their own.

ACT III: Renewal

The tradition of democratic socialism continues to be important to everyone involved at Dissent. But we are not, primarily, utopians; our job isn’t just to tell people who are unhappy with the way things are going that they need to enlist in our cause. We take seriously people who are engaged in struggles anywhere in the name of greater democracy, greater equality, greater freedom.

—Nick Serpe, 26 years old, Dissent online editor, interviewed in 2013

You are not allowed to complete the work, yet you are not allowed to desist from it.

—Rabbi Tarfon, Pirkei Avot (The Book of Principles), 2:21, ca. First Century C.E.

Dissent greeted the 1990s with guarded optimism (and with a new co-editor, Mitchell Cohen, professor of political science at Baruch College and the CUNY Graduate Center, who joined Howe and Walzer at the top of the masthead in the Spring 1991 issue). The end of the Cold War raised hopes of a “peace dividend” in the form of declining military spending. Mark Levinson, writing in the April 1990 issue, noted that in the Reagan years the defense budget doubled, while social welfare spending declined 40 percent. “If this kind of shift could take place in less than a decade, there is no reason why a shift in the other direction should take any longer.” And in a wild, three-way race for the presidency in 1992, incumbent Republican George H.W. Bush proved surprisingly vulnerable. As Harold Meyerson wrote in September 1992, before the results were in, “We may well be facing an election that will put an end to the conservative era that began in 1968.”

Mitchell Cohen, 2011

Those hopes were not unrealistic, but they were not fulfilled. In 1991, the United States went to war against Iraq, following Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, winning a victory that, as President Bush exulted, had ended the “Vietnam Syndrome.” The defense budget went uncut, as the United States, the last superpower standing, embarked on a new series of foreign interventions in the 1990s and beyond. Dissent’s editorial board, in the first such instance since the Vietnam War, divided on the wisdom of the 1991 war against Saddam Hussein—although even the pro-war voices warned against a full-scale invasion of Iraq.

Democrat Bill Clinton won in 1992, and in his first year in office brought before Congress a proposal for a form of national health insurance, a reform long supported by Dissent, although not in the particular form designed by Bill and Hillary Clinton. But when that proposal collapsed and its defeat was followed by sweeping Republican gains in the 1994 midterm elections, Clinton tacked sharply rightward.

A pattern had been established in the aftermath of the 1960s; each time the Democrats regained the White House, it became more evident that the New Deal order was past reviving. Clinton himself declared in his 1996 State of the Union Address that “the era of big government is over.” Political scientists eventually coined a phrase for this phenomenon, calling it “asymmetric polarization.” The Republicans moved ever farther to the right, while the Democrats shambled behind them in the same general direction. Watching the political center in the United States continually being redefined rightward was infuriating and depressing to Dissenters. In the run-up to the 1996 presidential election Harold Meyerson complained in the magazine:

[I]t’s not just suspense that’s missing from this year’s elections. It’s hope . . . . The party that once created old age pensions and unemployment insurance, the WPA and the TVA, the Civil Rights Act and the War on Poverty has shrunk itself into the party of V-chips and school uniforms.

Familiar themes continued to be debated in the pages of the Dissent in the 1990s, notwithstanding the ever-rightward trajectory of the politically possible. This included a continued debate on the meaning, relevance, and future of socialism (the latter often discussed in terms of some form of “market socialism”). Some on the left had hoped that the collapse of communism in 1989-1991 would lead to a revival of democratic socialism, in the United States and abroad, as socialists no longer had to distinguish their perspective from that of the “actually existing socialism” embodied in the former Soviet Union. Perversely, from the Dissentnik perspective, the opposite seemed to have occurred. The discrediting of Soviet Communism made it even more difficult to envision alternatives to actually existing capitalism.

The Summer 1994 issue of Dissent carried Eugene Genovese’s provocative essay, “The Question,” in which the formerly radical now resolutely conservative historian accused not only former Communist Party members like himself, but liberals and even anti-Stalinist socialists, of sharing guilt for the crimes of Stalinism. Throughout history, Genovese declared, “social movements that have espoused radical egalitarianism and participatory democracy have begun with mass murder and ended in despotism.” So much for the democratic credentials of Eugene V. Debs, Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela, and virtually everyone else whom Dissentniks had regarded as heroes and models. The editors and writers who commented on the piece in the same issue were not persuaded. Historian Christine Stansell declared that, for her part, “I am suspicious of a mea culpa whose main purpose is to castigate others.”

There were also new themes and emphases found in Dissent’s pages in the 1990s, including a series on Green Politics, articles on humanitarian interventionism, the impact of globalization, and, in general, an increase in international coverage. Much of the latter, including a 1996 special issue on embattled minorities around the world, was solicited and edited by Mitchell Cohen.

If in the 1970s and 1980s, Dissent skewed toward economic concerns; in the 1990s, questions of political philosophy came to the fore, as in Michael Walzer’s consideration of communitarianism, “Rescuing Civil Society,” in the January 1999 issue. Writers in the magazine examined “third way” politics in the United States, Britain, and elsewhere, and everywhere found it wanting. About the state and future of American politics in the later 1990s, there was little optimism. As Mitchell Cohen wrote in an editor’s note in the January 1999 issue, on the occasion of the forty-fifth anniversary of Dissent’s founding, if the original editors were still around

they would be disheartened by the state of American democracy. Dissent’sfounders understood a great deal about sectarian fanaticism, left and right. The same can hardly be said of the current Republican leadership. It seems to hate a president more than it cares for the country’s political health.

Then with the new century came the event in Dissent’s backyard that was to define the next decade. In an editorial entitled “Terror” in September 2001, rushed to the printer within days of the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Michael Walzer called on Americans “to speak quietly and act carefully.” Anticipating the call to launch what came to be called the Global War on Terror, Walzer insisted, “Terrorism has to be fought cell by cell: resolution and stamina are necessary; intelligence and police work, not military posturing.”