Booked: How the League of Nations Shaped International Politics

Booked: How the League of Nations Shaped International Politics

Tim Shenk talks to historian Susan Pedersen about The Guardians, and how the bureaucrats of the League of Nations helped to destroy the imperial order they had set out to protect.

Booked is a monthly series of Q&As with authors by Dissent contributing editor Timothy Shenk. For this interview, he spoke with Susan Pedersen about her new book The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire (Oxford University Press, 2015).

World domination is reserved for supervillains, but global governance is the terrain of bureaucrats. That has been the case since the aftermath of the First World War, when the League of Nations was born. Though little remembered today, the history of the League is now being recovered by a new generation of scholars. The Guardians is the latest, and most impressive, product of this turn. Joining a global scope to deep archival research, Susan Pedersen reveals the process by which a group of supposedly apolitical technocrats at the League helped to create a new kind of international politics and to destroy the imperial order they had set out to protect. But the collapse of empires left behind a world of entrenched inequalities—and that, too, is part of Pedersen’s story.

—Timothy Shenk

Timothy Shenk: If I had to guess, I’d say that most people think of the League’s history (when they think about it at all) as somewhere between tragedy and farce. For a long time, historians tended to share that perspective. But your book is part of a trend in recent scholarship that has taken us, as you put it in an article for the American Historical Review, “Back to the League of Nations.” What has encouraged historians to return to the League, and how has this new work changed our understanding of the organization?

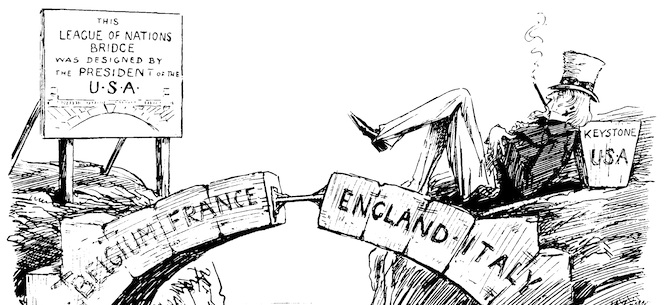

Susan Pedersen: There are lots of reasons why the League is coming back into focus, but I think two are most important. The first is that the uncertainties of our present time rather mirror those of the interwar period. We live in a world that is no longer bipolar, in which the major global power is, frankly, in relative decline, but in which the role that will be played by the coming powers isn’t terribly clear. That’s rather like 1918–39. The League was set up to manage the settlement of 1919, but it was too partial, too linked to the victorious allied powers, too tied to the imperial order, and too harmed by the U.S. decision not to join to do that effectively.

The second reason the League is coming back into focus is that it was the incubator of a lot of the institutions and practices of global governance we live with now. The World Health Organization grew out of the League of Nations Health Organization, UNESCO out of the League’s Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, ECOSOC out of the Economic and Financial Section of the League, and the list goes on. The quiet work of League bureaucrats set many of the frameworks and protocols for today’s global governance.

Shenk: You describe The Guardians as a “comprehensive history of the mandates system—that is, of the League’s effort to manage the imperial order.” What territories was the League called upon to “manage,” and how did the League end up with this responsibility in the first place?

Pedersen: The League didn’t actually govern any territories: it oversaw the administration by the Allied powers of the African and Pacific territories seized from Germany and the formerly Ottoman Middle East. In the Pacific, Japan seized the Caroline, Marshall, and Mariana Islands from Germany, New Zealand took over Western Samoa, and Australia occupied German New Guinea; in Africa, Britain and France occupied and partitioned German Togo and Cameroon, South Africa occupied South West Africa (present-day Namibia), Belgian forces took over Rwanda and Burundi and the British tried, without much success, to subdue German forces in East Africa. At Versailles, Germany had to surrender those territories. All the occupying powers wanted to annex those German colonies, but American opposition and a genuine international revolt against colonial rule across the world made that impossible. Various humanitarian lobbies in Britain had been pressing during the war for new international agreements over colonial rule; Arab nationalists in the Middle East were determined to achieve independence.

So the mandates system was hammered out in Paris as a compromise from the start. It was designed to grant actual administrative control to the powers who had conquered these territories while affirming a measure of international control. The mandated territories were supposed to be governed in the interests of the local population, so there were various stipulations outlawing slavery and limiting forced labor and other abuses; they were also supposed to be “developed” in the interests of the world as a whole, so all League states were granted equal rights to enter and do business. A Permanent Mandates Commission comprised of so-called “experts”—most were former colonial officials—was set up to receive reports from the powers administering mandates and was supposed to alert the League Council to any abuses. It took years to set the system up, though. The imperial powers had agreed to League oversight to placate the Americans, and when the United States didn’t join, most transparently hoped the whole plan would just go away. Only some hard work by the League’s officials, and an outcry over South African repression of an uprising in South West Africa, forced the imperial powers to finally agree to comply with the requirements to begin reporting to Geneva.

Shenk: The leaders of the mandates system, you write, became “inadvertent architects of a world they had not imagined,” and this question of unintended consequences is one of the book’s preoccupations. What purpose was the mandates system designed to serve, and why did that goal prove so difficult to achieve?

Pedersen: The mandates system was clearly set up to stabilize the settlement reached in Paris, and to win agreement to Allied administration of these territories. The oversight regime was supposed to set standards for imperial rule and—through the publicity inherent in the Geneva system—show the world how well the Allies were governing. But publicity cuts two ways. In the system’s early years, populations in South West Africa, Syria, and Western Samoa rose up against their new governors, and the fact that the League had to investigate those uprisings meant that these populations’ grievances were broadcast around the world. Instead of stabilizing the imperial order, the system turned into a mechanism for challenging it.

Shenk: The Guardians is filled with memorable figures, but one of the most remarkable is a Samoan named Olaf Nelson. Who was Nelson, and what did his experience reveal about the mandates system?

Pedersen: Nelson was the son of a Swedish trader and a high-rank Samoan mother, which meant he was classed as a “European” by Samoa’s German rulers and then by the New Zealanders who took over under League mandate. He was also the main copra trader in Samoa, and one of the islands’ richest men. Nelson identified with both the European and the Samoan population and helped bring the two together in a movement known as the “Mau” to demand self-government. Nelson argued, reasonably enough, that the Samoans were perfectly capable of running their own administration, and he also objected to the argument that “Europeans” and “Samoans” were distinct groups and had to be governed differently.

One of the most shameful episodes in the history of the mandates regime is the treatment of Nelson. Essentially, the League’s Mandates Commission colluded with the New Zealand administration to paint Nelson as an opportunistic schemer; he was condemned by the Commission and banished from Samoa by the New Zealand administrator. I think this episode shows how profoundly racial thought structured the League system. The members of the Mandates Commission genuinely thought the Samoans—those 90 percent of Samoan men who signed petitions calling for self-government—needed protection and not rights. They were completely bewildered when the Samoans continued to petition the League for self-government after Nelson’s banishment, and even more nonplussed when Samoan women took over running the movement when the male population went into hiding. I think it is this episode that shows most starkly the way a commitment to “protect” a native population can slide into efforts to make sure it is sufficiently subjected and disempowered to require “protection.”

Shenk: Most of the territories the League superintended were former colonies of Germany, but Germany itself did not become a member of the League until 1926. How did Germany’s entry change the League’s approach to international governance?

Pedersen: Nothing had a greater impact on the League’s effort to legitimate imperial order than Germany’s entry into the League. This was because Germany ended up playing a completely unexpected role. Everyone knew Germany wanted its colonies back. But in the Weimar period the German Foreign Ministry concluded that goal was unrealistic, and instead decided to insist that the promises made at Versailles—that all the mandated territories should be governed in the interests of the international community and open to all League states—be strictly adhered to. So, entirely unexpectedly, it was Weimar Germany that insisted most strenuously that the imperial powers were not sovereign in the mandated territories, that those territories had to be economically open to all League states, and that they should be made independent as soon as possible. Germany didn’t do this because they were sympathetic to independence movements; in fact, Foreign Ministry officials admitted privately that if they still had colonies they would argue differently. Their view was: if Germany couldn’t have its colonies back, it was in Germany’s interest to make sure that no one else benefited from them either. Even more than the United States, in the Weimar period Germany played the role of the “anti-colonial” Great Power.

Shenk: As that suggests, debates over sovereignty—that is, over who had ultimate authority—provoked the fiercest disputes in the Mandates Commission. By the end of the 1920s, you write, these clashes had helped produce a new model—a “decoupling of legal sovereignty and economic control” that prepared the way for our own “world of normative state sovereignty, even when accompanied by diminished state capacity.” The supposed emancipation of Iraq in 1932, which you say was more like “the creation of a client state,” provided one template for this approach. What does that history tell us about the shifting meaning of sovereignty?

Pedersen: Sovereignty matters: I’m not arguing that it doesn’t. But, as Antony Anghie argued before me, what the League helped to create was a kind of “damaged” sovereignty: a sovereignty that could be extended to Third World states while preserving significant imperial economic control. The mandates system was far from the only arena in which these unequal bargains were worked out—but the Iraq case is, I think, especially illuminating. The Mandates Commission really didn’t want to approve Britain’s plan for the independence of Iraq in 1932 precisely because they felt that—with British-dominated international conglomerates still controlling Iraq’s oil fields and the RAF controlling its airfields—Iraq couldn’t be said to be “truly” independent. But Iraqi elites and Iraqi nationalists understood that this was the only “independence” on offer, and collaborated with the British to induce international agreement. The French and Italians agreed when their share of oil was confirmed. This is a particularly stark example of the neocolonial bargain in formation.

Shenk: While I was reading The Guardians, there was another book that kept on popping into my head: Recasting Bourgeois Europe, Charles Maier’s classic study of France, Germany, and Italy in the 1920s. It was published forty years ago, but it’s a masterpiece that’s still very much worth reading today, and it makes a persuasive case for the enduring significance of that period for the world after 1945. Was Recasting a model you had in mind, and, even if not, do you think the comparison tells us something about where historians have moved since that book appeared in 1975?

Pedersen: Maier was one of my two dissertation supervisors, and Recasting Bourgeois Europe had a huge influence on my early work on the European welfare state. His influence on The Guardians is less direct, but his commitment to constructing complex models of causation is one I completely share. I think Recasting is prescient, too, in its awareness of the way models of governance spill across national lines and have to be studied in an international context. Economic stabilization after the First World War was a transnational project, and so was imperial stabilization. It’s true that, forty years on, we tend to see different things: anti-colonial activism and protest play a major role in my book; I’m interested in how conflicts outside Europe affect the European order. But Maier too was trying to understand how the global order changed after 1918, and this book is also part of that effort.

Shenk: You don’t spend a lot of time on it, but it’s clear that a theory about politics motivates your analysis, and that one of the major influences is Max Weber. The Guardians could even be described as an extended reflection on how legitimation works (or doesn’t). What does seeing the history of the League with this question of legitimacy in mind reveal?

Pedersen: It’s true that the mandates system really was an effort at legitimation. But what the system hoped to legitimate was imperial rule—and what I hope to have shown is that the world had so decisively changed by 1918 that that effort was bound to fail. The mandates system legitimated the Versailles settlement in the eyes of Western publics, but most populations under mandate—especially in the Middle East—never accepted that claim.

Max Weber also, of course, offered us a perceptive theory of political leadership, contrasting the “politician of ultimate ends”—that is, a politician who is driven exclusively by a particular ethical imperative and refuses to calculate costs—with a “politician of responsibility” who understands his or her obligation to think through the consequences of any action in a real-world context. I hate to say it, but I don’t think anyone in the book really lives up to Weber’s quite strenuous ideal of the “politician of responsibility,” although some of the League’s officials—notably the Swiss professor William Rappard, who was the first Director of the Mandates Section in the Secretariat and then a member of the Mandates Commission until its demise—comes close. To find such a person, you’d have to go back to my last book and learn about Eleanor Rathbone, Britain’s most effective interwar female politician.

Shenk: Another major theme of the book is the importance of bureaucrats. They’re “unglamorous historical actors,” as you note, but they had considerable influence at the League and, through the League, over much of the world. “Bureaucracy, more than idealism,” you write, “tamed the demons of power.” What does focusing on the bureaucrats let us see that histories of movements at the grassroots leave out?

Pedersen: International bureaucrats are a pretty unusual species of bureaucrat. In national administrations, you have a public sphere of electors and civic organizations and lobbies, and then a realm of government, of which bureaucrats are a part. But in the international arena, bureaucrats are supposed to be loyal to internationally agreed norms and covenants, even though political capacity and power, and to an extent civic activism as well, still reside largely in nation-states. This means bureaucrats play an especially important role in the international arena: they are middlemen, mediating between international ideals and national interests. Most are pragmatists, not idealists; they also are citizens of individual states and always subject to pressure by their governments. But insofar as anyone represents “the international” in the interwar period, they do. Privately, they have quite a lot of influence, and very occasionally they step outside their supposed “non-political” role and take public stands.

Shenk: The mandates system, of course, eventually collapsed, along with the League of Nations. The assumption of global leadership by the United States, the rise of the Soviet Union as a major power, and the wave of decolonization that swept across the postwar world—all of that marked a profound break from the world the League sought to manage. But you argue that there was more continuity than this picture suggests. What, ultimately, was the legacy of the history you tell here?

Pedersen: What I think the mandates system did was establish an arena of debate and struggle over the question of what “independence” would mean. The norms the League tried to enforce—of the “open door,” of free labor and free trade, of the “non-sovereignty” of imperial governments—prefigure the implicit contract made during decolonization and help us to understand the world that emerged after 1945. But I think the mandates system shaped not only the content of that postcolonial bargain but also the practices of global politics after 1945. During the League period, both imperial powers and nationalist movements learned to orient their claims toward an international public and international organizations in Geneva. Today, those battles are fought out at the UN. During the League period, a number of imperial powers learned that they could “win” militarily—in Syria, in South West Africa, in Palestine—but “lose” diplomatically; they discovered that “staying on” wasn’t worth the cost. That’s a pattern that was played out on a global scale after 1945. I tend to think the battle for imperial legitimacy was lost in the League period—even if it took the war, and a lot of anti-colonial postwar struggles, to finally bring those lessons home.