Life from All Sides

Life from All Sides

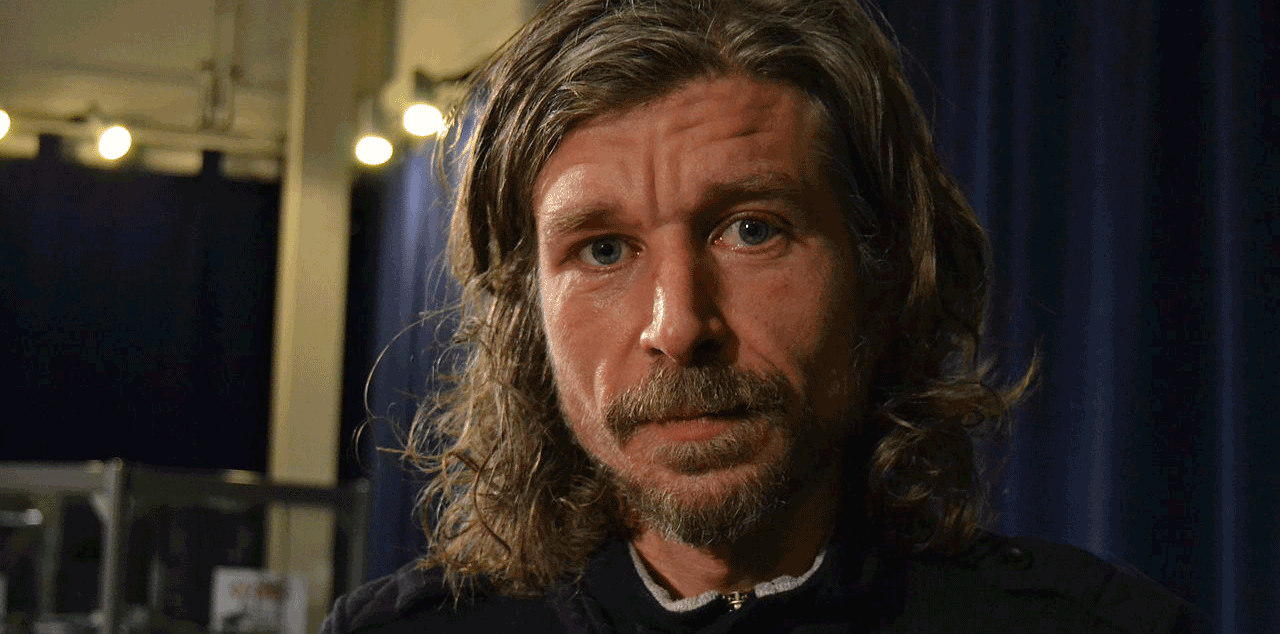

At the heart of Knausgaard’s struggle is the possibility of understanding—between himself and his family, himself and his readers.

Seasons Quartet

by Karl Ove Knausgaard

Penguin Press, 2017–18

Near the end of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Dolly, the model of a devoted wife and mother, travels to visit her sister-in-law, Anna, who is living in scandal on a country estate with her lover Vronsky. As Dolly watches the Russian countryside pass by from the carriage window, “all the thoughts she had repressed crowded suddenly into her mind, and she reviewed her whole life from all sides as she had never done before.” Musing on topics from the mundane (her children’s eating habits and wardrobes) to the mortal (the death of a son in infancy), Dolly finds herself questioning the forces that had governed her fifteen years of married life. “It is all so incomprehensible and difficult,” she thinks. “And what is it all for? What will come of it all?” Dolly arrives at no definitive conclusions, continuing in her domestic roles as before. Yet her questions linger, never far from her—or the reader’s—mind.

Recent work by the Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard can be read as an attempt to examine a “whole life from all sides.” What for Dolly took shape as a four-hour respite from child-rearing has for Knausgaard become several books, including the six My Struggle novels. In the first two volumes, Knausgaard documents a landscape of encounters and objects (family dinners, cassette tapes, Rembrandt), his relationship with his abusive father, his two marriages, and the birth of his first three children. In volumes three, four, and five, there are more family dinners, white Nikes, and Flaubert; we learn about his childhood, sexual awakening, struggle with alcoholism, and ambition to become a writer. The final volume charts the publication and reception of the first book, including a lawsuit filed by an uncle, unhappy with the portrayal of a brother. The series courses along for nearly 4,000 pages, yet Knausgaard’s clarity of voice and his compulsive, convulsive attention to detail means that nothing feels repetitive.

In Knausgaard’s writing, the family is the source from which life flows, giving it form and content while limiting its possibility and scope. It makes sense that Tolstoy is one of his heroes. Family defines the characters in War and Peace and Anna Karenina, novels that map politics and history along the arc of childhood, motherhood, and fatherhood. Tolstoy himself had thirteen children, and a fraught relationship with his wife. When Dolly realizes that her children give life its shape and substance, it leads her to question the meaning of her social role. Knausgaard’s central struggle emerges from a similar process. The more he locates himself within the family, the more he discovers the point where the utterly dull (diapers, mealtimes, laundry) merges with life and death. The more he realizes this, the more he is subject to his family’s demands, more firmly entrenched in his role as father and husband.

Knausgaard’s descriptions, like Anselm Kiefer’s oils, constitute a search for “depth in surfaces.”

If the six My Struggle volumes show Knausgaard coming to terms with these recognitions and restrictions, the Seasons Quartet shows another side of these tensions. For as much as family limits Knausgaard’s life, it also allows him to see power in a new way.

The Quartet is framed as a series of letters, journal entries, and vignettes addressed to his fourth and youngest daughter. She is in utero in Autumn, born midway through Winter, three months old in Spring, and a toddler in Summer. Many of the chapters are only a page or so long. All volumes feature illustrations throughout the text, which supply content as well as form. In one episode in Summer, for example, Knausgaard pays a studio visit to Anselm Kiefer to select paintings for the book; Knausgaard observes how the artist achieves with color and visual form the sense of time and proximity he searches for with words. “For that was what I experienced in Kiefer’s paintings, the different velocities of time in the material and in the human world, and a continual search for depth in surfaces, which is the curse of every painter but with Kiefer seems to be an obsession.”

Knausgaard’s descriptions, like Kiefer’s oils, constitute a search for “depth in surfaces” that in the Quartet excavates the causes and origins of things. To do this, Knausgaard must strip himself of habitual ways of seeing and thinking: “And the task of art is to see something as it really is, as if for the first time.” Who but a baby sees in this way? For Knausgaard, to be a father is to be an observer, a role that gives urgency and purpose to his writing. The task to describe the world to his daughter becomes a process of de-familiarization in order to make sense of life.

The world is full of things in need of explanation. In Autumn and Winter, Knausgaard describes everything from blood (“Like everything else found inside the body, with the partial exception of the brain, the blood doesn’t know what it is doing”); coins (“Our whole society is built around the belief in the fiction of coins, and the moment that belief vanishes, society collapses”); and toothbrushes (“[the children] are at pains to assert their property rights over everything that is theirs and don’t allow anyone to use any of their possessions without prior permission [. . .] yet they are indifferent to ownership when it comes to toothbrushes”); to concepts like “the I” (“The distinctive thing about life, what distinguishes it radically from non-life, living matter from dead matter, is will. A stone wants nothing, a blade of grass wants something”) and “the local” (“And perhaps that is how we should imagine the universe, not as something alien and abstract, all those dizzying numbers and vast distances, but as something nearby and familiar”). In each case, Knausgaard moves from elemental description to an account of use and circulation in the world. Objects aren’t simply material—they are cultural and social, too.

Seasons quickly change, like lives and literary form. In Spring, the catalogue of things gives way to a continuous narrative that lasts just over one day. There is a reason for this. Early on in the book, Knausgaard describes to his daughter a meeting with Child Protection Services, one year before her birth. “It was a routine meeting, they always arranged one when it happened, the thing that had happened here, but it didn’t leave me unaffected . . .” Knausgaard, in his mid-forties, describes his shame as he answers questions posed by two young social workers.

What was it, “the thing that had happened here”? Like a photograph in a darkroom, details gradually come into view. Knausgaard writes to his daughter that they are going to visit her mother, who is in the hospital. There are descriptions of friends and acquaintances who have attempted and committed suicide. There are descriptions of his wife’s depression and her struggle, their struggle, to get help.

Life, like the cruelest season, marches on. Knausgaard and his daughter go to the ATM, run errands, pick up the other kids from school. As the picture of their family life develops, the quotidian blurs with the philosophical. Knausgaard’s task to explain the world to a baby becomes a task to explain why life is worth living. What is it all for? What will become of it? Answers are buried within minor fights, disagreements, daily routines, frustrations between parents and children, brother and sister, parent and parent. There are times, Knausgaard explains,

when feelings got out of control, a chain reaction might occur in which [my children’s] actions snagged on mine and finally made me explode in ways I hadn’t experienced since I myself was a child, when my vision could suddenly cloud with anger. Even when we were among other people I sometimes lost my temper completely. Once I roared THAT’S ENOUGH! THAT’S ENOUGH! to your elder sister in the middle of a shopping centre, she was maybe two and a half years old, and I slung her over my shoulder and carried her like a sack out to the street while she screamed and kicked and I fumed inwardly. Obviously people stared, I let them stare, I was in a place where other people and their opinions didn’t matter.

In the angry contest of parent versus child, brute force wins. Yet what is most interesting about this passage is the way that Knausgaard questions the legitimacy of his own actions as he narrates them. What are his grounds for disciplining his daughter? A series of “snagged” emotions, feelings let loose, a vision “clouded with anger”? It is not hard to recognize that the adult is the one behaving badly.

If there is any kind of lesson learned in this episode, or even throughout the book—and Knausgaard is quick to confess his missteps to the reader—it is that what shapes our engagement with others is always something less mediated than we realize.

Spring ends, and Summer begins. Returning to the format of Autumn and Winter, Summer has entries on household appliances, popular culture, and ice cream. But something is different. It is impossible to read Summer—the bike rides at dusk, neighborhood BBQs, the endless parade of afterschool activities—without “the thing that happened here” in mind. Though his tone and style stay the same, Knausgaard marks a shift in his own thinking by adopting the persona of a woman, based on a real acquaintance of his grandfather during the Second World War, a technique reminiscent of his second novel, A Time for Everything, a retelling of biblical stories from multiple perspectives. Caught in a loveless marriage with several children, the woman has an affair with a German soldier stationed in Sweden, a choice that leads to violence and troubling consequences. (The significance of Kiefer’s paintings, often taken to represent Germany’s reckoning with the Nazi past, here takes on added charge.) Knausgaard’s thoughts merge with hers, and her story and its dark conclusion wind into his diary entries and vignettes. The result is a lyrical and disorienting interiority.

For the woman, the damage she does to her family damages her in return. “The woman I am writing about knows what she has done and reflects upon it; while she has forgiven herself, she has not been able to prevent it from ruining her life.” This process of coming to terms with her past enables Knausgaard to understand the effects of his own action, and inaction, on those nearest him. It also gives him reason to pause.

Though, how can a life be ruined? In relation to what? [ . . . ] To reconcile oneself with one’s fate, the expression goes, and it means just this: understanding that life turns out the way it does, that nothing can ever be redone, that there is no other path to be taken than this one, which ends the moment you die and, as it were, draw the ladder up after yourself. It is a thought I find comforting. We do the best we can.

But what, we might still reasonably ask, is it for? After all, Knausgaard’s project is nothing new: a number of contemporary writers have dealt with the trappings of life with children and the struggle to reconcile the demands of domesticity with the imperatives of writing and art-making. Authors such as Rachel Cusk, Heidi Julavits, and Sheila Heti depict the family as a space sealed off from politics and art—it is a source of anxiety, distraction, impossibility. Other writers, such as Maggie Nelson, Elena Ferrante, and Knausgaard, show the family as a path to the wider world. For them, it is a fertile ground for contest and deliberation, where its members train themselves in the messy reality of political conflict.

At the heart of Knausgaard’s struggle is the possibility of understanding—between himself and his family, himself and his readers. This understanding comes through the stripping apart of objects and structures, the peeling away of surfaces for depth, the examination of life from all sides. Though Knausgaard arrives at no definitive conclusions, he is ready to see power in a new light. What he will do with this vantage point remains in his hands, for him to do the best he can.

Ana Isabel Keilson is a lecturer on Social Studies at Harvard University. She is currently writing a book on politics, culture, and modern dance in Germany.