Mississippi Fever

Mississippi Fever

In River of Dark Dreams, Walter Johnson draws on slave narratives and planter magazines that the slave order was riven by contradictions and headed for a crisis. At a certain point, the desperate lurches of the slaveholders, the intense longings of the enslaved, and the increasing boldness of abolitionists, both black and white, had to lead to a steamboat-style explosion, whatever the precise political conjuncture.

Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom

by Walter Johnson

Belknap Press, 2013, 560 pp.

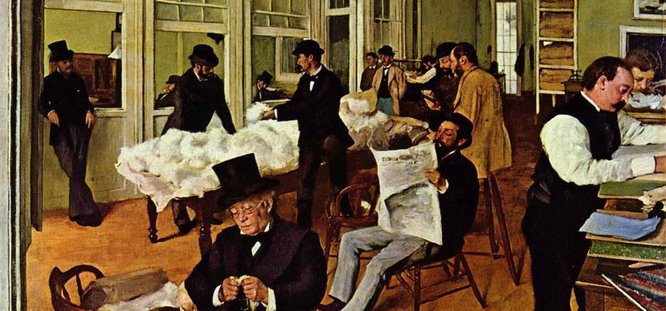

The “dark river” of the title is the Mississippi, and the chapter on the “steamboat sublime” furnishes a compelling account of the role of steam—and slavery—in the rapid opening up of the Mississippi Valley, making it, within a few years, “the leading edge of the greatest economic boom the world had ever seen.” U.S. cotton planters were able to supply the textile manufacturers of Britain and the world with a tensile fiber that was exactly suited to industrial methods (as wool and flax were not). The pleasant feel and convenience of cotton goods, the ease with which they could be washed and ironed, were a vital component of a consumer revolution that embraced other plantation products.

Who is to say whether all this might have been achieved without captive laborers? The fact remains that it was not. Indeed, it was the sale or dispatch of around a million enslaved persons to the new cotton regions of the Southeast and what was then known as the Southwest (Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Mississippi) that enabled the planters to steal a march on white men with no slaves and bring the best lands quickly into cultivation. As Johnson explains, “Indian removal” on a quasi-genocidal scale was also part of this great leap forward. These rapacious proceedings created an agrarian complex based on racial slavery worth about three billion dollars in 1850s currency.

The hundreds, soon thousands, of steamboats, piled high with bales of cotton, hovered between floating warehouses and mobile palaces. When Johnson dubs this the “steamboat sublime” he is not imposing some alien trope from cultural theory. Time and again this was the word that contemporaries reached for to convey their feeling that the steamboats were “beautiful, awesome and inexplicable.” Yet Johnson is not content with the mystery and probes the checkered history of the first large-scale application of steam to overground transport. Reduced to essentials, the steamboat was some fretwork atop a raft powered by a high-pressure engine. Unfortunately that type of engine was prone to explode (as a thousand did). The steamboats were also vulnerable to the notorious “snags”—logs or tree stumps lodged in the river bed—that wrecked many an oncoming vessel.

If there had not been such a hectic rush to bring as much cotton as possible to market, these problems could have been tackled (for example, by using low-p...

Subscribe now to read the full article

Online OnlyFor just $19.95 a year, get access to new issues and decades' worth of archives on our site.

|

Print + OnlineFor $35 a year, get new issues delivered to your door and access to our full online archives.

|